When local elections are held a year into the term of a UK government, it usually sees the electorate (well, those who bother to turn out) expressing their dissatisfaction with the government by voting against councillors from the party of power in Westminster.

After a general election loss, the opposition can often expect to make mid-term wins. Witness, for example, Labour’s achievements at a local level even in the worst years of the 1980s. This pattern has held over the past half century.

While the council elections taking place across the UK aren’t quite mid-term contests, a year is enough to have some expectations that the government will take a hit. Government ministers usually have to spin narratives about their losses being expected because they are making tough decisions.

On the other side, opposition politicians normally spin from scripts about encouraging progress and how the electorate is starting to realise their terrible mistake at the previous general election.

But the script has had to be changed in 2016, even if no party had to throw it in the bin definitively.

Labour losses

The Labour narrative, in particular, has reoriented. This is the result of the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader and the clear attempt to radically shift the party’s political direction.

Labour has made losses across the country but the interpretation of how serious they are really depends on who you ask. It depends heavily on whether the individual genuinely supports the leader, feels obliged to support the leader or is publicly seeking evidence of electoral failure to undermine the leadership.

In terms of share of the vote it appears that in key wards, Labour is up 4% on 2015 – not a disaster, but hardly a clear endorsement of Corbyn’s leadership or evidence of a party as yet building towards triumph in 2020.

In other words, too strong a showing for the leader’s many internal enemies to mount a leadership challenge and just sufficient for loyalists to stress the novelty of the Corbyn project and how we are aren’t yet in mid-term.

For England, at least, the changes to the political landscape were quite marginal. Labour made some gains in difficult areas, such as Birmingham, Southampton and Exeter but appeared to be heading for a net loss of 26 councillors across the country.

Even with a victory for Sadiq Khan in the London mayoral race, Labour will find it hard to draw much optimism from the results. The situation in Scotland cannot be spun as anything other than a continuation of the catastrophe that began in the 2015 general election.

Tories tough it out

The Conservatives have found it much easier to spin the night as encouraging. Yes the party was down about 4% on its 2015 general election results, and yes this is consistent with Labour being slightly ahead in the country as a whole (when the non-voting areas are considered) as opposed to being behind in the opinion polls. However, the Conservatives ended the night controlling as many councils as at the start and with a net gain of eight councillors.

That’s only a very small positive change but it comes after a year of further austerity and some very unpopular decisions.

UKIP running out of steam?

UKIP secured very encouraging results in heartlands such as Thurrock, but overall it gained control of no new councils and had a net gain of just 20 councillors. Furthermore, it is reasonable to argue that given the EU referendum and the fact that everyone is thinking about their main issue, the party should have made more progress – an interpretation regurgitated by UKIP’s opponents all night. Labour has also argued, with some justification, that UKIP had failed to pose a meaningful challenge in its Northern heartlands.

For the Liberal Democrats, the narrative was clearly that a perilous decline has been halted – but this positive message was repeated alongside sombre recognition that the party still has much work to do.

Most years Liberals and Liberal Democrats can be heard predicting that a political realignment is imminent, but this narrative has been disrupted in recent times, as decades of Liberal Democrat progress were reversed by catastrophic losses during the party’s five years in government.

This trend continues with disappointing result in Stockport, a hung council which it had led, and in many areas failed to even begin to start the re-building process. It was the largest party in Southampton a few years ago, for example, but has failed to win any seats at all this year.

The Liberal Democrats even saw their target ward of Portswood, which they consistently won for approximately three decades, switch from Conservative to Labour. Across England, the Liberal Democrats retained control of two councils with a net gain of just 13 councillors.

So this election has produced small changes, and sufficient ambiguity for all parties to defend their performance. However the Conservatives are probably most justified in taking satisfaction. Nevertheless, 2020 is a long way ahead and actually these results make little difference to who runs local government.

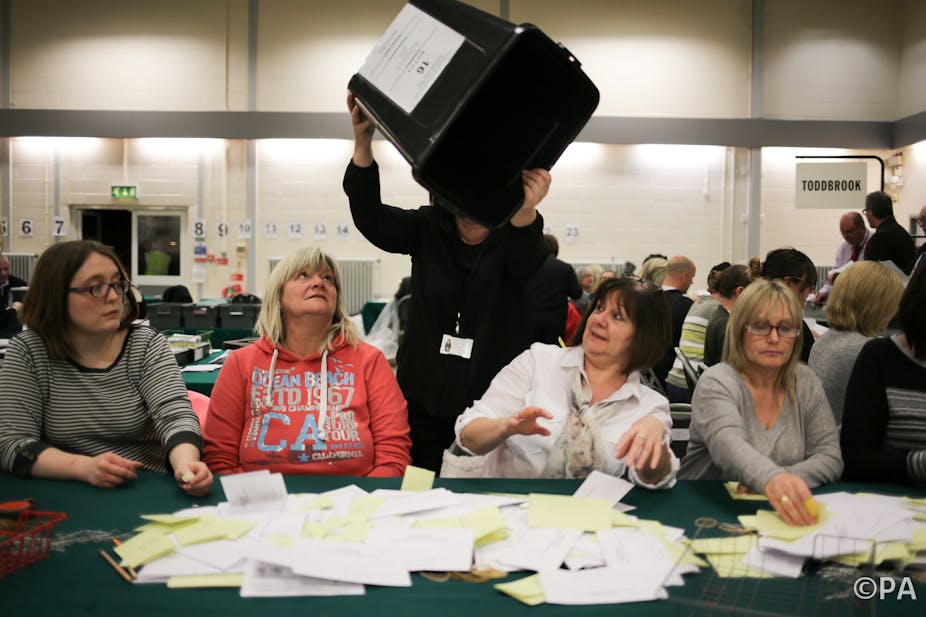

Votes were still being counted when this article was first published.