There has been lots of talk lately of a “tech bubble”. The NASDAQ composite index - a widely observed benchmark of the high-tech sector - last week reached the level of 4000 for the first time since the dotcom boom thirteen years ago.

At the same time we read eye-catching news stories about high-profile social media stocks. Big-name companies such as Twitter and Facebook have gone public and made billions for their early investors. As these brands are well known the story and the positive sentiment about their stock prices reaches far outside of established investor circles.

Startup firms with ideas and technology but no track-record are again attracting huge valuations. Messaging app Snapchat recently turned down a $3 billion offer from Facebook. Investors now apparently value it at US$4 billion. Snapchat’s revenue? Zero.

All of this is reminiscent of the “dotcom boom”. But we shouldn’t believe the hype. In making investment decisions we should read the data rather than the big news stories. Sure, there may be some extraordinary valuations around, but we aren’t in another “tech bubble”. I remember holding all those “hot” stocks myself in the late 1990s and this time round both the sentiment and the numbers tell a completely different story.

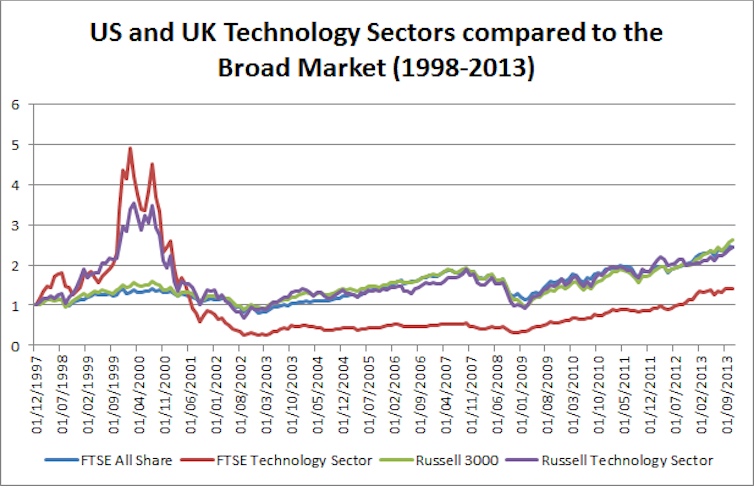

This chart shows how four different investment choices made on 1st January 1998 would have worked out if they were held until today. The choices are: US tech sector (Russell Technology); US broad market, or overall stock market (Russell 3000); UK tech sector (FTSE Technology); UK broad market (FTSE All Share).

The dotcom boom and bust around 2000 is clear to see. If you invested in the UK tech sector on 1 January 1998, your investment would have gone up more than five-fold at the height of the bubble. But just two years later your original investment would have dropped to 20% of its original value. Those are astonishing multiples.

The US experience parallels this but is less extreme. The gain from 1 January 1998 to the peak is just over three-fold. The popping of the bubble is less painful too, with performance after the burst just reverting back to that of the broader market.

Interestingly, since the dotcom bubble burst the performance of the UK tech sector has lagged behind that of the broader market. An investment in the UK tech sector made in 1998 would have only regained its initial value about a year ago.

If you had invested in the overall market you would have missed out on most of this excitement and you would have fared much better. The lines for the broad market indices look positively serene in comparison.

But technology investors can take heart from how “un-bubble like” things look. Recent performance of the US tech sector actually looks much the same as the broad market.

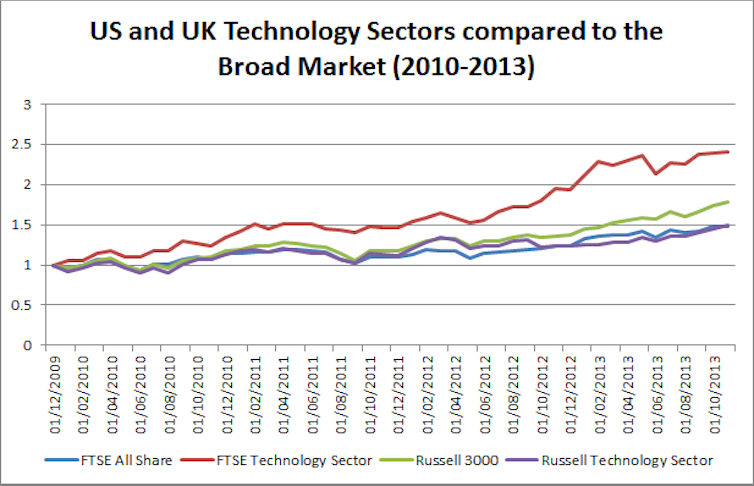

The choice of reference frame influences our perceptions. Perhaps the feeling of a bubble in the UK is amplified by the UK tech sector’s recent outperformance. If we redraw the above graph with a start point of 1 January 2010, this is clear to see.

However, over the longer timescale we might be more inclined to see this as the UK tech sector making up lost ground, rather than a bubble.

Big numbers like 4000 for the NASDAQ don’t represent danger thresholds per se, although they may appear that way to uninformed minds. Even the all-time high of over 5000 would not ring alarm bells now.

Bear in mind that at the height of the dotcom bubble, the average company on the US tech index was valued at 200 times its earnings. Today that price to earnings ratio stands at a mere 24. Tech companies today are generating far more profits relative to the price of their equity.

The media loves to concentrate on extremes of success or failure. We can safely ignore them. The averages indicate that if there is another tech bubble on the way, it has barely got started.