The term “hipster” has become increasingly prominent in Australia’s urban lexicon this year. Even the Sydney Morning Herald has caught on, writing about “Hipster Housing”, featuring a young bespectacled couple on the front of the weekend property pages.

It is a rather scathing phrase, used at the moment primarily as a criticism. Across the cartoons, jokes, video parodies and feature articles, a caricature emerges.

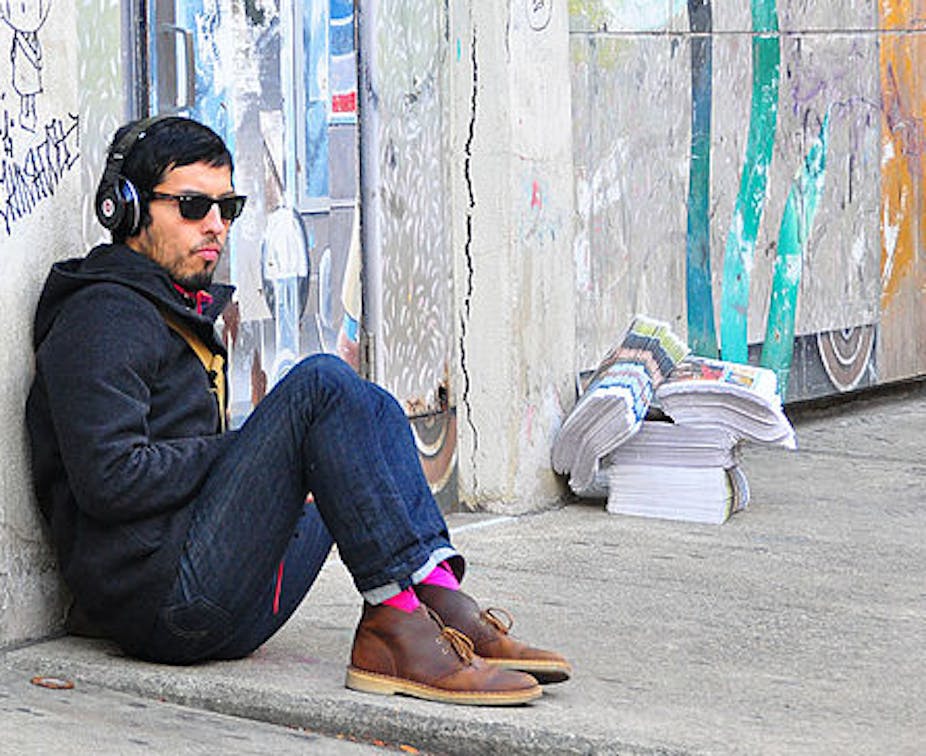

The hipster is that funny smelling kid in tight jeans who sits in front of you on the bus or tram, pre-rolling cigarettes and judging you through his Ray Bans because you don’t have an ironic tattoo, 80s facial hair or read the zine he and his friends author.

Yet my own experience with hipsters indicates that such representations share only a partial, albeit humorous, likeness to reality.

How to define a hipster

Further reading of the hipster commentary will see some gross inconsistencies emerge.

For some critics, hipsters are all about the latest trend, whereas others argue vintage and kitsch are more highly valued. Some say hipsters wear their jeans around their knees, yet others claim high-waisted pants to be the preferred style. Hipsters are simultaneously mocked for both insisting on individualism and adhering to conventions.

Overall, the varying media definitions of hipsters inevitably oversimplify what is actually quite a complex and significant cultural happening.

Underneath subculture

Perhaps the biggest problem in trying to qualify the hipster movement is the tendency to use a subcultural lens, which suggests there are a coordinated group of people performing these social acts with reason and intent.

Granted in Sydney there are bars (Chingalings, The Cricketers Arms), music festivals (Laneway, Peats Ridge) and suburbs (Newtown, Surry Hills) where hipsters visibly congregate, but any notion of solidarity or collective ideology will be shattered if you ask these people if they think they are hipsters.

The most likely response is a strong refutation, often on the grounds that they were into, for example, vintage shops before they even knew what a Hipster was.

An ironic concession is also possible; “Yes I am the most hip hipster around, and I pride myself on that achievement.”

In a sense, both responses typify the hipster concerns of authenticity and subversion respectively. But attempts to see these responses as universal are also unsatisfying. Furthermore, if you are undertaking such bizarre ethnography, you are surely on the cusp of hipsterism yourself.

Rebelling and conforming

The other imposition on hipster culture is that it is resistant. Loose ties to independent media, youth rebellion, and past subcultures (including the original 1950s hipsters fabled in Norman Mailer’s essay “The White Negro”) may have aided this diagnosis.

The immediate irony of non-conformity is that it inevitably leads to conformity of another kind; adherence to a new canon. This hypocrisy underpins a lot of the criticism of hipsters, yet there is another level of hypocrisy worth noting; the mainstream is becoming increasingly hipster.

The hipster aesthetic has emerged as the best form of sellable cool. Sydney publicans James Wirth and James Miller (The Flinders, The Abercrombie) have cottoned on to this nicely, purchasing formerly run down Sydney Hotels and revamping them with some tragically stylish memorabilia, cool music and attractive bar staff (a formula so successful even Sydney hospitality heavyweights Justin Hemmes and the Short brothers have been trying it out).

Fast-food chains like Grill’d, Beach Burrito and Mad Pizza e Beer are all working on a similar charm. And most midrange car commercials these days seem to show hipsters bopping around carelessly to indie music.

Hipster vs punk

All this might seem to disqualify hipsters from the category of subculture. But even the original punk scene in London – perhaps the most mythologised of subcultures – was equally complex and contradictory.

What lent punk a singular narrative, crystallising it as an actual culture, was not its protagonists, but rather the media. The subsequent process of (mis)representation and reinterpretation was so unpredictable that punk music popped up some years later in America as the sound of Neo-Nazism.

Perhaps the best way to rethink the issue is to consider a subculture the way we think of a national culture. Individuals or groups within a nation are both influenced by and distinguish themselves from the national culture, which whilst not without convention, is largely an abstract and fluid concept.

Furthermore, people do not belong specifically to this culture, but rather it is one of many that constitutes their identity and levels of association can vary greatly. Subcultural involvement is much the same.

Hipsters gone global

However, just as with punk, simplistic representations of hipsters cannot be separated from the lived experience. Hipsterism is a global phenomenon, suggesting the way it has spread is largely due to information exchange.

Furthermore, the day-to-day lives of hipsters, or people who look like hipsters at least, are affected by the stereotype promoted through the media and parody; hipsters might call other hipsters, hipsters insinuating they are merely following a hipster cliché. As you can see, it’s easy to get caught in circles here and things can get a bit surreal.

Whilst employed as an insult, and overused of late into relative ambiguity, the uprising of the term “hipster” has ultimately had the effect of strengthening an array of ideologies and styles that have been around for a while.

It is a cognitive social shift that can’t be removed from gentrification and the new style of “creative workspaces”, and it is not likely to slow given the strong presence of hipster types in the media promoting its use, even if through criticism.