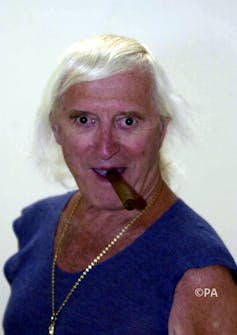

The original BBC documentary by Louis Theroux in 2000 about Jimmy Savile, the former British TV star thought to have sexually abused at least 500 women and children, was uncomfortable viewing even before his crimes were common knowledge. Watching with the benefit of hindsight, one moment that really sticks out in When Louis Met Jimmy is when Theroux finds a notepad with his ex-directory phone number on it. “There’s nothing I cannot get,” Savile tells him.

Theroux revisits the moment in his new documentary, Louis Theroux: Savile. It is a statement of Savile’s power that helps us understand why his victims – a number of whom Theroux interviews in the film – found it so difficult to speak out while Savile was alive. Some are clearly still haunted by their failure to do so.

Theroux mostly acts as witness to their testimonies, aware of his own complicity in the myth-making that ensured their silence for so long. Yet as much as these victims deserve to be heard, the way their testimonies are framed is troubling. Louis Theroux: Savile is meant to be about the relationship between these two men. By persistently asking Savile’s victims how he got away with it, Theroux ends up effectively implicating them.

To be fair, there is never any question that he accepts their accounts of feeling some responsibility. But all the same, allowing them their moments of self-blame without making any comment leaves the viewer with the sense that their silence and his ignorance are equivalent. It’s a lost opportunity to reflect on the structures which supported Savile and effectively silenced these women.

Shattered histories

Theroux also confronts three women who in different ways question the accounts of Savile that have emerged. First up is Janet Cope, Savile’s PA of nearly 30 years, who echoes much of what she has said in the press before. Savile emerges from her description as controlling, manipulative and cold. But ultimately, she defends him. “He didn’t do it,” she says categorically, noting that the allegations relate to a “different era” when she was “grateful if somebody gave me a pat on the bum”.

Another interviewee is Gill Stribling-Wright, a researcher and producer on Savile’s BBC shows who knew him for decades. Stribling-Wright tells Theroux she hasn’t read Dame Janet Smith’s report into Savile at the BBC. What, she asks, would she do with it if she did?

The sense of the psychic trauma inflicted upon those close to Savile is even sharper in the account of Sylvia Nicol. Nicol worked with him at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire, south England, where his abuses have become notorious. She still has photos of Savile half-hidden in her home, and a large Lego bust of him intact in her garage. “I’m a victim” she tells Theroux, “a victim of losing those memories”.

These interviews raise difficult and uncomfortable questions about the private legacy of a disgraced public figure. With Savile now so thoroughly expunged from the archive that the BBC apologised after a clip of him was mistakenly shown on a Top of the Pops rerun, how do those who cared for him, who worked with him, whose lives were intertwined with his, make sense of their own histories now?

Questionable decisions

At the same time, some serious gaps undermine Theroux’s efforts to understand how he (and others) were duped. Most seriously, Savile appears as a complete one off. There is no mention of the broader Operation Yewtree enquiry into celebrity sexual abuse, nor the convictions of the likes of Rolf Harris, Max Clifford and Stuart Hall and the other arrests that followed the Savile revelations.

The new documentary acknowledges that the Savile investigations resulted in major enquiries in the NHS, BBC and the police, but Theroux interviews no representatives. He focuses almost entirely on individual and not institutional culpability.

That the individuals in focus are all women is meanwhile deeply troubling. The structure pits woman against woman, moving between the victim testimonies and the interviews with Cope, Stribling-Wright and Nicol.

What about all the men who benefited from their connection with Savile? Who abused alongside him. Who eulogised him on his death. Who defended him by their own inaction within the NHS, the BBC, and the police.

That Theroux does not find a single man willing to be interviewed gives a very distorted picture. If none of Savile’s male friends, family or colleagues were willing, that in itself would require comment. Theroux’s own footage from his 2000 documentary shows at least two of Savile’s male friends. Despite the liberal revisiting of that original, neither appear here.

The one other man who does appear is Tony Hall, director general of the BBC, speaking at the release of Smith’s report in February. Hall is removed, watched by Theroux on television in a press conference at the time. Unlike some of Theroux’s female witnesses, Hall has no personal links with Savile and is apologetic and willing to acknowledge responsibility.

Theroux’s documentary barely scratches the surface of the questions about BBC failures raised by Smith, as Mark Lawson, The Guardian’s arts critic, has already pointed out. But neither Lawson nor Theroux acknowledge Smith’s fundamental point about the “macho culture” at the BBC that enabled Savile’s abusive career.

There is nothing macho about Theroux’s self-examinations, but in choosing to only place women in the dock alongside him over a 75-minute documentary, he has inadvertently contributed to a culture in which women are held responsible for men’s violence against them. It is a horrible misstep. It suggests there is still a lot of work to be done to unravel the unthinking sexism which helped him to abuse with impunity.

The only interviewee to directly challenge the blame implicit in Theroux’s questioning is Angela Levin, a former Daily Mail writer, introduced as the source of the rumours he originally heard about Savile. “Don’t blame this on me,” she asserts.

Certainly there are as many important questions to be asked about individual responsibility as that of the institutions in this whole saga. But by asking these questions only of women this documentary contributes to the problem it attempts to unravel. And it lets abusive men, and the institutions which enable them, off the hook.