The World Health Organisation (WHO) took an historic step in the fight against malaria when it recently recommended the use of a malaria vaccine for young children. The announcement marked a major achievement – the development of the first ever successful malaria vaccine against falciparum malaria, the deadliest form of malaria and the one that is most common in sub-Saharan Africa.

The wide uptake of the vaccine could prevent thousands of deaths in the region. According to the 2020 World Malaria Report, over 250,000 children under the age of five years died of malaria in Africa in 2019. That is a very sombre statistic for a treatable and preventable disease.

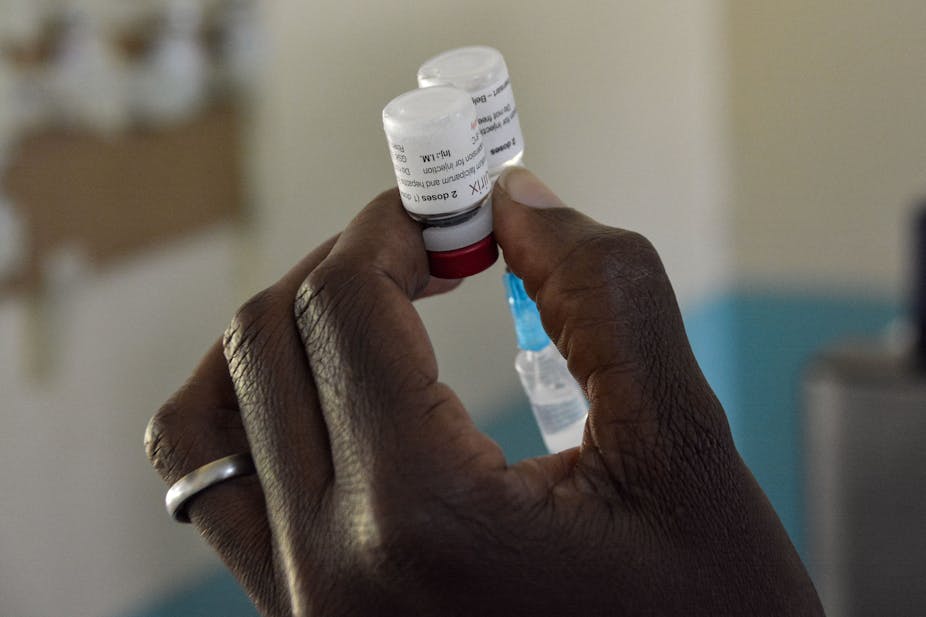

The development of the vaccine (called RTS,S) has taken over 30 years. It is the culmination of work by researchers from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, in partnership with the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and the global health organisation PATH.

Producing an effective malaria vaccine has been challenging as the malaria parasite is able to hide from the human immune system. In addition, different forms of the malaria parasite infect the liver and red blood cells.

Read more: Why does malaria recur? How pieces of the puzzle are slowly being filled in

Vaccine trials were started in 2019 in three African countries – Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. The study showed that the RTS,S vaccine was safe in young children, that it reduced hospitalisation and death in vaccinated children by over 70%, and that a successful malaria vaccination programme was possible in rural African settings.

The pilot study also showed that the vaccine was able to reach children who were not being protected by other methods like bed nets in the study sites. This provided additional support to the calls for the widespread use of the vaccine in malaria-affected areas.

Since 2015 malaria case numbers have been either flat or on the rise. This follows 15 years during which the numbers had been on the decline.

The addition of the RTS,S vaccine to the malaria control and elimination toolkit could get global efforts back on track. But it cannot be viewed as the silver bullet required to achieve malaria elimination.

Not a complete solution

The vaccine has several shortcomings.

Firstly, in its current form it only works very effectively in very young children, aged between five and 17 months. These children must be given three vaccine doses, at least one month apart. A fourth booster dose is recommended at 18 months for the vaccine to work optimally.

This is makes running an effective vaccination programme very challenging. One possible solution is using community-based vaccination programmes to increase access and improve compliance.

In addition, although the vaccine prevents severe disease, it doesn’t necessarily prevent infection. This is similar to the COVID-19 vaccines.

Thirdly, it’s only effective against one (Plasmodium falciparum) of the five human malaria parasites.

Read more: Breakthrough malaria vaccine offers to reinvigorate the fight against the disease

There are other concerns too. One is increased vaccine hesitancy across Africa.

There are also likely to be challenges in meeting the demand for vaccines, given the current focus on producing COVID-19 vaccines.

In light of these challenges, the RTS,S vaccine cannot replace existing effective interventions. These include indoor residual spraying and the use of insecticide treated bed nets. Instead, the vaccine must be used alongside these to break the malaria transmission cycle.

As the RTS,S vaccine is only effective in young children, it will only be used where they are at higher risk of infection than older children. Such conditions are generally found in moderate to high transmission areas. In these areas, frequent malaria infections result in older children developing partial immunity.

This immunity prevents children from showing the signs and symptoms of malaria. They become asymptomatic carriers of malaria. Many malaria-endemic African countries, including Botswana, Eswatini, Namibia and South Africa, have very low transmission intensities, so the population does not develop immunity against malaria.

Including the RTS,S vaccine in a childhood immunisation programme in these low transmission countries would not be cost-effective.

Despite the challenges associated with the RTS,S vaccine, its addition to the suite of malaria control interventions is a leap forward in the global fight against malaria. But vaccine innovation must not stop here. Efforts must be put into developing a vaccine that is effective in older children and adults, which requires only one dose and is effective against all human malarias.