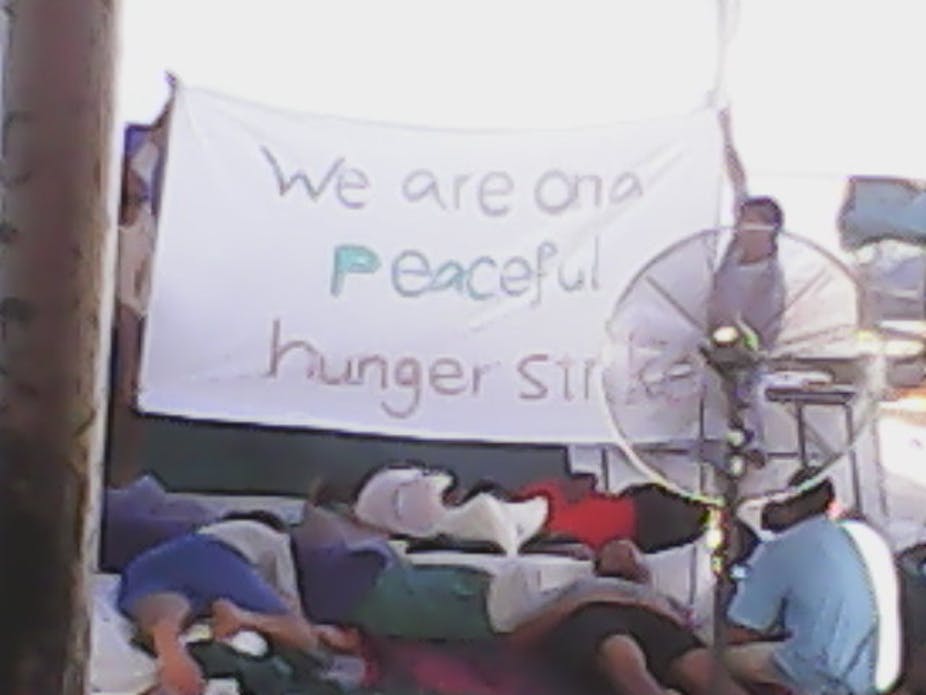

Reports continue to emanate of escalating hunger strikes among asylum seekers at the Manus Island detention centre in protest at the length of their detention and their conditions.

The Australian government has taken a hardline stance. It is publicly refusing to negotiate with the protesting detainees. Last Friday, Immigration Minister Peter Dutton said:

My message today is very clear to the transferees on Manus and in other facilities: whilst there has been a change of minister, the absolute resolve of me as the new minister and of the government is to make sure that for those transferees they will never arrive in Australia.

The Abbott government’s response so far echoes that of previous governments, which have seen hunger strikes as manipulation or blackmail, to which “we” (Australians and the government) will not give in.

To view hunger strikes in this way is to profoundly misunderstand the protest. It leads to unhelpful and potentially dangerous responses, which go directly against expert advice based on evidence, practice and study of managing hunger strikes developed across more than a century of experience from India to Turkey, to the UK, Ireland and Australia.

The possible consequences of such wilful ignorance could include the death of one or more people under Australia’s care. A healthy man of average weight in his mid-20s can sustain a hunger strike while continuing to take fluids for between six and ten weeks. If there is a refusal of fluids, deterioration of the person’s health is accelerated and death is expected to occur after between seven and 14 days.

Hunger strikes have a long history and have been used by prisoners, protesters and disempowered groups around the world. It is rarely a first action in protest against a perceived wrong – it is generally embarked upon only when other courses of action have been exhausted. When people’s words repeatedly fall upon deaf ears, they have little choice but to use their bodies.

We have met with and listened to several former immigration detainees who participated in hunger strikes, including some who sewed their lips. They explained that they had tried repeatedly to talk to the Department of Immigration. Most commonly, they received no response at all to their requests or, at best, they received a non-specific bureaucratic response of “your claims are being processed” with no substantive acknowledgement of their grievances, much less any engagement.

Former detainees have told us of their growing sense of powerlessness and despair. As they progressively lost all hope in “the system”, they searched for ways to communicate and to be heard beyond the faceless inhumane bureaucracy.

A hunger strike is a dramatic, but civil form of protest. It is civil because it is ultimately a communicative act: it seeks to send a message and open up pathways for discussion and negotiation. It is a radical departure from impersonal bureaucratic communication. It is intended to shock, to bypass the system and reach out directly to:

… the conscience of viewers, forcing them to recognise that they are implicated in the spectacle that they behold.

Detained asylum seekers are hunger striking not to speak to a bureaucrat, but to us – fellow human beings. The hunger strike makes visible their suffering, which is currently hidden behind razor wire and exclusion zones. The hunger strikers are asking us to see their suffering – their shared humanity – to connect with us on the basis of conscience and to ask ourselves if this is morally (rather than legally or politically) acceptable.

A hunger strike relies on the interconnectedness of human beings and on human conscience for its power. It speaks to the gaoler and onlookers, implicating us in the dialogue, and requests a response. One young man told us he was sure that sewing lips forced people to question what was happening in detention centres:

John Howard was saying “they are criminals” and media were backing it up. But after that we saw how it changed and people started to … journalists, lawyers, everyone, those who saw something in there, you know. I mean, they sew their lips. “Why do they sew their lips?” Not just “seen sewing lips” but going for the reasons of why. Just asking a question … That’s what was good about all these protests, you know, just reflecting our feelings to another human being, just to see us not as a danger but as another human being who escape from danger.

Ramatullah, a spokesperson for detainees on hunger strike at the Woomera detention centre in July 2002, said the hunger strike was to:

… show the cruelty of persecution on us. If we die, it will make conspicuous our innocence and the guilt will be on the government.

Another young man who spent three years in detention said he believed that such physical protests would reach a sympathetic audience:

At least you can find somebody who has a good heart, they can say something. People they were sewing their lips and throwing themselves onto the razor wires and stuff, they were messages. Messages from the people in the detention centre. For example, those messages made this Petro Georgiou or other backbenchers or something to push the government: “What are you doing? What are you doing with these people?”.

The hunger strike underway on Manus Island must be taken seriously – by those directly managing the centre, by the Australian and PNG governments, and by us, ordinary people reading reports of it. The protesters have been detained with little or no progress on their refugee claims for 18 months. They have endured conditions which are, by all reports, woefully substandard.

Detainees on Manus Island have survived a violent attack, which killed one man, and observed as another died from a preventable condition. Their immediate future is uncertain and unappealing. Their complaints have failed to generate any meaningful response.

The government’s response invalidates asylum seeker concerns, fears and distress. People are impersonally “managed” using threat, punishment and violence.

Lost in all of this is the realisation that asylum seekers are human beings just like everyone else. They need to feel safe and know their future is secure.