In the 1980s there was a concerted attempt to downgrade, even eliminate Shakespeare from popular consciousness.

Cultural studies practitioners argued there was little point in performing and revering plays that seemed anachronistic and irrelevant to modern times. Feminists said the same of a male writer, deriding the patriarchal attitudes in his works. Postcolonial critics persuasively railed against the British literary canon.

In 1989, however, Kenneth Branagh’s filmed version of Henry V (cleverly timed 50 years after the outbreak of the Second World War), hit a global nerve. Extracts were played on national radio, full of fine language and stirring music.

Even more unexpectedly, in 1996, Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet attracted audiences of tearful teenagers in millions around the world. The argument that Shakespeare’s plays could not be popular with modern audiences of all ages was looking shaky.

Meanwhile, the postcolonial subjects themselves, in countries such as India and the USA, refused to answer the call to give up Shakespeare. In fact there is a strong argument that Shakespeare had for some centuries ceased to be a “British-owned” commodity, since his works had been translated by writers revered as national icons in their own right – Goethe in Germany, Pasternak in Russia, and celebrated film-makers such as Kurosawa in Japan. I’ve heard the Sonnets read in translations in Noongar, Urdu, Hindi, Chinese, French, Czech and Korean, and I’m certain they exist in virtually every other language on earth.

Feminists, too, began to reclaim his works, reinterpreting them as creating assertive, independent and outspoken women – Cleopatra, Rosalind, Portia, Lady Macbeth, Queen Margaret of Anjou – who voiced eloquent attacks on gender inequality. Germaine Greer’s Cambridge PhD was a far from unsympathetic study of Shakespeare’s comedies. More recently, she published Shakespeare’s Wife (2007).

Triumphantly rehabilitated as “Person of the Millennium” in 2000, celebrated on his 450th birthday in 2014, and now the subject of unprecedented, global attention 400 years after his death, there seems no sign of Shakespeare going away again any day soon.

But even if the unthinkable were somehow to happen and all traces of Shakespeare’s names and works were eradicated from the modern world, his influence would remain around us. He has made, and changed, history.

For instance, we would still have the almost 2,000 new words Shakespeare either coined or imported into the English language – words like “bedroom”, “excite”, “blood-stained” and “zany”.

Ditto the myriad phrases (such as “a foregone conclusion” from Othello), which may sound proverbial but come from Shakespeare. And the hundreds of titles of books and movies shamelessly taking phrases from the plays.

Among classic novels we find Under the Greenwood Tree, Remembrance of Things Past, The Sound and the Fury, and Brave New World. In movies, North by North-West, Rich and Strange and The Dogs of War. This is not even to broach the multiple operas, ballets, symphonies, musicals, and songs inspired by his works.

Decisive historical events have been framed and driven by Shakespearean analogies. In 1865, US President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in a theatre, shot by the famous actor John Wilkes Booth, whose brother Edwin had recently played Brutus in Julius Caesar.

Apparently John Booth coveted the role. Taking method acting to an extreme, he choreographed the event with the play’s assassination scene in mind. He is said to have intoned “Sic Semper Tyrannis” (thus always to a tyrant) directly after shooting the president.

In the first and second world wars, both sides enlisted Shakespeare for his morale-raising speeches. Laurence Olivier’s 1944 film Henry V was funded by the British Ministry for Information. In one scene, arrows from longbows fly into the distance and eerily metamorphose into RAF bombers. Naturally the British made the most of the propaganda possibilities.

Hitler and the Third Reich appropriated Hamlet as an Aryan German soldier, and used The Merchant of Venice for anti-Jewish purposes. The Nazis embraced Shakespeare in pamphlets such as “A Germanic Writer”.

In South Africa when the African National Congress was outlawed, travelling players went from village to village playing Macbeth, news of their clandestine arrival passing by word of mouth.

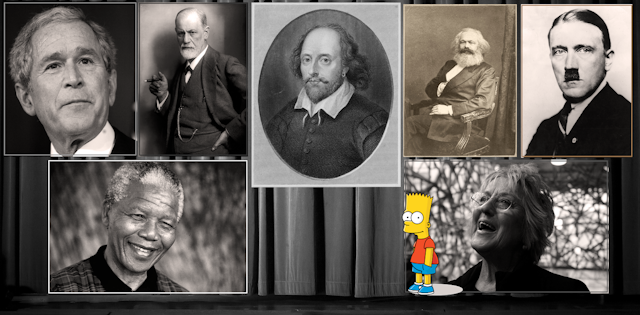

Under apartheid, Janet Suzman courageously cast a black actor and a white Desdemona in a famous and galvanizing production of Othello. Nelson Mandela found inspiration by constantly re-reading a copy of Shakespeare’s complete works while in prison.

In countries as different as Poland, Egypt and Serbia, productions of Shakespeare’s master-narratives that depict the overthrow of tyrants became provocative calls for rebellion against regimes and dictators. Many were closed down by state authorities.

Stalin took Shakespeare’s subversive influence so seriously that he banned Hamlet from theatres in Russia.

More recently, George W Bush proclaimed Henry V as his favourite literary work. And Barack Obama has been likened to Hamlet for his perceived procrastination in foreign interventions (still, better Hamlet than Coriolanus, for the world’s sake).

Shakespeare’s indelible influence has also been indirect, working through figures whose works have profoundly entered modern thinking.

Sigmund Freud acknowledged his debt, basing some of his most famous theories on Shakespeare’s plays, especially Hamlet but also Macbeth and The Merchant of Venice. Melanie Klein wrote profoundly on King Lear and absorbed it into her psychoanalytical practice. More recently, psychotherapy has constructed theories of analysis using Shakespeare’s role-playing theatrical practice.

In the field of economics and politics, Karl Marx kept returning to passages in Timon of Athens and King Lear to develop his theories of inequity and redistribution of wealth.

Shakespeare was bedtime reading for Marx’s children. His daughter Eleanor had learned whole passages by heart by the time she was three.

These days, in contrast, business studies departments around the world workshop among executives role-playing scenes involving Richard III and other Shakespearean kings.

Speaking of indirect influence, popular culture has soaked up Shakespeare. He is regularly quoted in The Simpsons and a whole episode of Doctor Who returns the Doctor to Elizabethan England to influence the writing of some plays.

Advertisers regularly use his memorable phrases to spruik their wares, while Hollywood and Bollywood plentifully reuse his plots, with or without acknowledgement, relying on a familiarity factor.

One story, Romeo and Juliet, has been regularly cited in films and news reports depicting love that blossoms in conflict trouble spots around the world, such as Belfast, the Gaza Strip, Bosnia, Kashmir, and elsewhere.

The phrase “a Romeo” has become synonymous with a certain kind of male romantic lover, and Juliet on the balcony is probably the most recognisable scene in the world, even when the words are yanked out of context and misunderstood: “Wherefore art thou Romeo?” (“wherefore” means “why”, not “where”). Meanwhile, “falstaffian” is used to describe a robustly comic person.

The extraordinary global attention given to Shakespeare 400 years later not only retrieves the past but traces how historical inscriptions of feeling states have shaped modern consciousness.

Shakespeare’s comedies of love, his tragedies of doomed families, as well as his Sonnets, have given us paradigms of emotional experience that still unconsciously guide our thought processes and emotions. To this extent, he has even taught us how to think and feel.