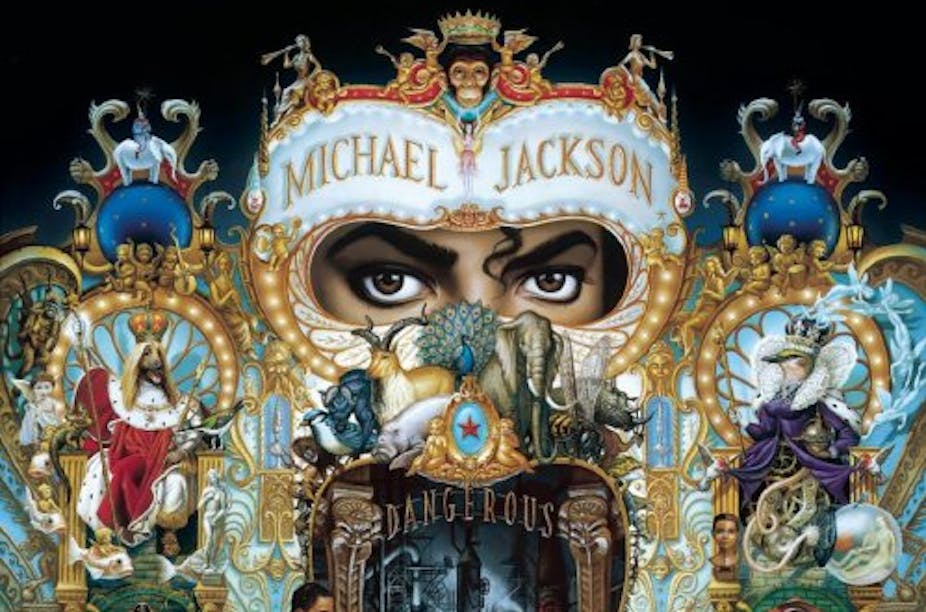

The album cover for Michael Jackson’s album Dangerous was painted by American pop-surrealist artist Mark Ryden. In it, he depicts a world in which the boundaries between human and animal, living and dead, whole and part, and celestial and terrestrial have been crossed and fused.

Surrealist painters like Ryden often aim to collapse such categories – to reconcile, in their art, what seems to be irreconcilable in life. But actually, this boundary-crossing does happen in life – increasingly so – and corresponds to what some have called posthumanism.

Cary Wolfe, an English Professor and author of the book “What is Posthumanism?,” writes that we are “fundamentally prosthetic creatures,” that we rely on entities outside the self – other humans, animals, technology – in order to function and thrive.

In other words: the boundaries of our bodies and intellect are not as firm and finite as we want to believe.

Posthumanism also argues for the dismantling of the hierarchy that puts humans – largely because of our ability to “reason” – above other forms of life and technology.

Both of these ideas were central to Michael Jackson’s life and art.

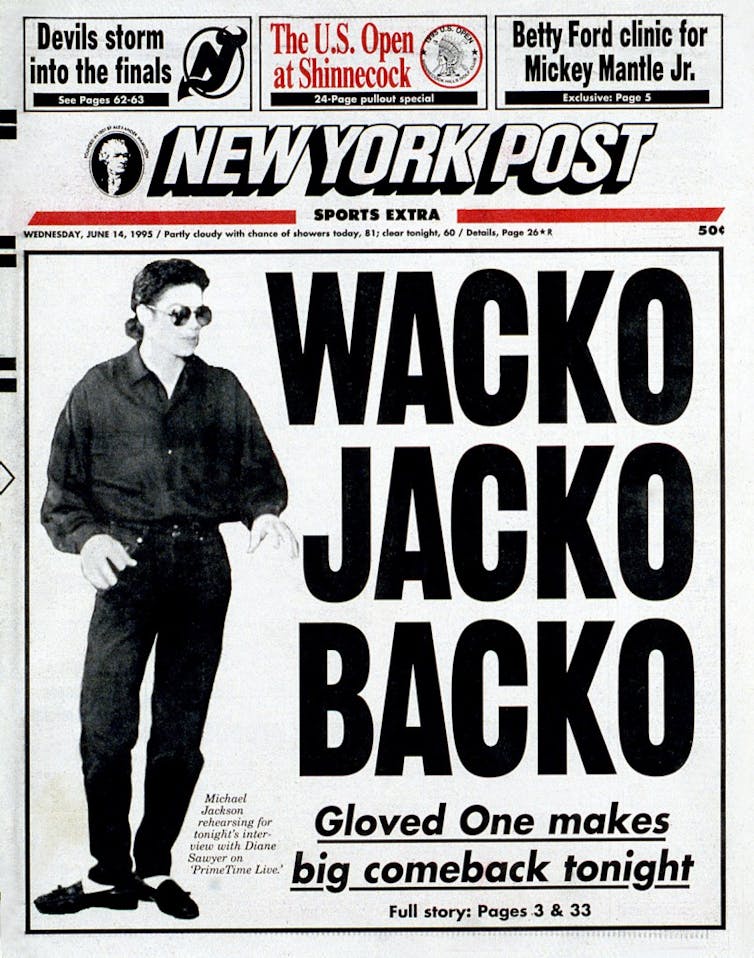

It’s somewhat surprising that so few have considered him through this lens; instead, many have simply labeled him as weird or eccentric.

Yet Jackson’s entire career was defined by his rejection of normal boundaries. This includes not only the most obvious of these (race and gender) but also generational barriers, the limits of his physical body, and divisions among real and fictional species – not to mention the seamless way he could fuse artistic genres.

Jackson celebrated the prosthetic idea of the human in a number of ways. For example, through plastic surgery, cosmetic procedures, make-up, hair styles and costumes, he asks us not only to reconsider gender binaries (that’s the relatively easy part), but to question prevailing ideas about aesthetic beauty and what can be called “normal.” Our appearances are all products of outside intervention (even face creams and nail files count); Jackson’s extreme modifications could be thought of as a commentary on this.

Fictional boundary-crossing was also a characteristic of his artistic practice – where, at various points, he presented himself as a werewolf, a zombie, and a panther. In the film Moonwalker he morphs into a spaceship; in Ghosts, he becomes a dancing skeleton, a grotesque monster, and a gigantic face that blocks a doorway.

Ghosts, in fact, is a film in which he addresses the perception that he is a “freak” and “abnormal” directly. It’s remarkable that so much of his morphing in this film is focused on his face – an object of constant scrutiny and derision in the media.

In both his life and his art, he held out his body as a work in progress, fully open to and trusting in limitless experimentation. There’s quite a long tradition of artists who have engaged in body modification as a means through which to test the limits of the flesh, like Orlan and Stelarc.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Jackson’s physical changes was the lightening of his skin. We should keep in mind that this was the result of the skin disease vitiligo. It’s thought, erroneously, that his skin color simply got lighter, but it actually fluctuated – so much so that his intent was certainly far from wanting to “be” white, as many have concluded.

Instead, it’s possible that vitiligo – painful as it must have been for him – served as an opportunity to start a conversation about race and skin color. He wanted to challenge the idea of race as fixed or linked to biology, rather than socially constructed.

Jackson’s boundary-pushing extended to his notion of family, which can be described as a sort of “queer kinship.” This has nothing to do with sexual orientation, but with how he challenged normative ideas about what constitutes family. His family included animals (Bubbles the chimp, yes, but also Muscles the snake and Louis the llama). It included children (Jackson could still play like a child, with children, when he was an adult, testing ideas about the normal, linear progression from childhood to adulthood). It included older Hollywood starlets, like Elizabeth Taylor and Liza Minnelli (again breaking the boundaries of normative generational affiliation); and it included Frank Cascio’s middle-class family from New Jersey, which Jackson adopted as his own, regularly showing up and spending time at their home, where he vacuumed and made beds with Cascio’s mother.

Much of this has been viewed as pathological because it’s a way of building family that does not conform; it crosses boundaries not normally crossed.

This makes many people uncomfortable.

But Jackson’s vision of the body and of kinship were actually forward-looking, a kind of reaching beyond societal norms that is often celebrated in other artists and activists, but still viewed with great suspicion in Jackson’s case. Elsewhere, I have argued that this is because Jackson crossed so many boundaries simultaneously. It was the combination of social transgressions that caused people to fear – rather than celebrate – his difference.

It was also that he truly lived these transgressions: there was nothing to mitigate Jackson’s differences. When other mainstream artists, like Lady Gaga, transgress boundaries on stage, the impact is often lessened by their private lives, which conform to societal norms.

In a 1985 essay about Michael Jackson, James Baldwin wrote that “freaks are called freaks and are treated as they are treated – in the main, abominably – because they are human beings who cause to echo, deep within us, our most profound terrors and desires.”

Michael Jackson – gender ambiguous; adored and reviled; human, werewolf, panther; black, white, brown; child, adolescent, adult – shattered the assumptions of a society that craves neat categories and compartmentalization.

Order and normality are illusions, he said though his life and art.