Foundation essay: This article is part of a series marking the launch of The Conversation in the US. Our foundation essays are longer than our usual comment and analysis articles and take a wider look at key issues affecting society.

On Tuesday, November 4, Americans will elect all 435 members of the US House of Representatives, 36 United States Senators, 36 governors, and thousands of state legislators and local officials. As we near the final stretch, horse race punditry and number crunching are coming into their own. Will there be a wave for the Republicans or will the Senate remain – by just a seat or two – Democrat?

What is less often discussed in the overheated television studios, however, is the context of this important midterm election and how attitudes and institutions have shaped the practice of politics in the United States.

Politicians – who needs them?

Motivated by a belief that power corrupts, Americans, more than the citizens in other modern industrial nations, privilege individual autonomy, free enterprise and social mobility. Although the size and scope of the state has expanded enormously during the last century, Americans continue to express skepticism about “big government” and advocate limitations on the authority of executives and legislatures to regulate behavior, levy taxes, and redistribute resources. During the past 30 years, these attitudes have informed the political agenda of both parties, rhetorically, and often substantively.

Absorbed in their daily lives and committed to the primacy of self and family, Americans often confine politics to a lower order of personal commitment than is generally recognized. They are neither interested in nor knowledgeable about politics. In a recent poll, for example, only slightly more than a third of respondents could name the three branches of government. More individuals could name a judge on American Idol than a justice on the Supreme Court. And, as the stunningly low approval ratings of Congress in 2014 suggest, Americans are likely to accord politicians a lack of respect that borders on contempt.

Low turnouts and their distorting impact

The massive election-day turnouts of white males in the second half of the nineteenth century, the heyday of party organization, masked the highly variable relationship of these Americans to their politics. The relationship included detachment as well as commitment. Citizens who aspired to middle-class respectability cared little for professional politicians or the saloon keepers, street toughs, and other unsavory characters the politicians employed. To be sure, they identified with party but many turned away from politics, often immediately, once the results were announced.

In the 20th century civil service reform supplanted the spoils system and parties lost control of the polling place. Alternative forms of entertainment emerged and electoral participation declined, even though the impact of government policies on every American increased.

Turnout is especially low in midterm elections. In 2010, for example, 90 million Americans (about 40% of eligible voters) cast ballots. Near the high end of the trading range for midterm elections since 1972, the total was substantially less than the 130 million who turned out in the presidential year of 2008. Many of the 2010 no-shows were young, African-American, and Latino, demographic cohorts that typically cast a high percentage of their ballots for the Democrats. Recently, moreover, several states have adopted voter registration laws to address electoral fraud, which critics have denounced as transparent attempts to suppress the political participation of poor people and members of racial and ethnic minority groups.

The turnout in primaries is even lower. Designed to replace nomination by party bosses in smoke-filled rooms with the will of the people, primaries have determined many of the candidates put forward by both parties since the 1970s. With “true believers” more likely than moderates to appear at the polls, primaries often produce candidates at the edges of the ideological spectrum.

In 2010, Christine O’Donnell won the Republican nomination for the US Senate in Delaware. She then spent much of her time in the general election assuring voters she was not a witch and lost a contest the established GOP candidate, former governor Mike Castle, may well have won.

In June 2014, in the Republican primary for the 7th Congressional district in Virginia, 65,000 individuals, about 12% of those eligible, cast ballots. 55% of them chose Tea Party favorite David Brat, a little known professor of economics at Randolph Macon College over Eric Cantor, the Majority Leader of the House of Representatives.

Here’s what Jim Messina, President Obama’s former campaign manager tweeted:

The danger of safe seats

An alarmingly large number of seats in the House of Representatives, perhaps the most in American history, are safely in the hands of one political party. Every ten years, the results of the census are used to re-calculate the number of seats in Congress awarded to each state. And each state, which usually means the political party in power, can redraw the boundaries of its election districts.

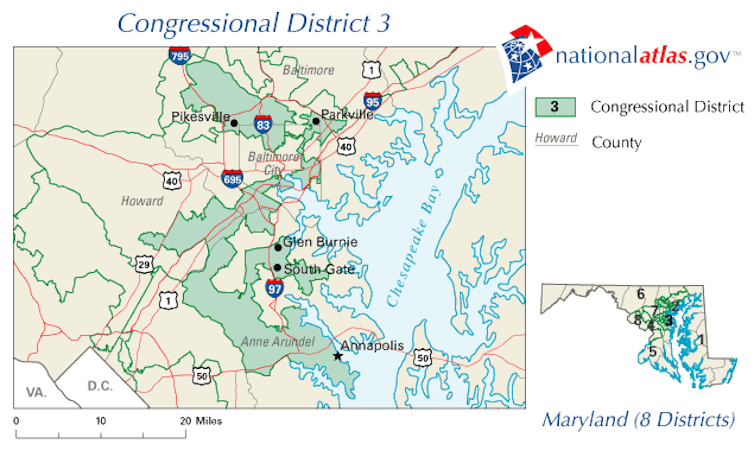

Recently, party professionals have used computers to assist in the venerable practice of “gerrymandering” (named for Massachusetts politician Elbridge Gerry): mapping congressional districts, at times giving them outlandish shapes, so voters of the opposing party are crammed into a small number of safe seats, while the party in power gets a larger number of seats it can expect to win by a comfortable margin.

North Carolina’s 12th district, meandering from north of Greensboro to Winston-Salem, then down to Charlotte, is the textbook example favoring the Republicans. Maryland’s third congressional district, the nation’s second most gerrymandered, is home to a Democrat.

In mid-September, the highly regarded Rothenberg Political Report characterized 212 Republican seats and 174 Democratic seats in the House of Representatives as safe – and only 49 as competitive or in play. Clearly, elected officials who can count on coasting to victory in general elections – and need fear “only” a primary challenge from within the party – have less incentive to reach across the aisle and seek legislative compromises.

Ideological chasms

During the past 40 years, both of the political parties have become more and more ideologically homogeneous.

When northern Democrats sponsored civil rights legislation in the 1960s and 70s, the once “Solid South” turned increasingly Republican, and the moderate wing of the Democratic Party, which was concentrated in the region, was decimated. At about the same time, the center of gravity of the GOP shifted to the Sunbelt, the party turned decidedly to the right during the “Reagan Revolution,” and its moderates, the so-called Rockefeller Republicans of the Northeast and mid-Atlantic states, became virtually extinct.

With ideology more closely aligned with partisanship, politics has become polarized. During the administrations of Bill Clinton, George W Bush, and Barack Obama, votes on major legislation, including health care, taxes, and economic stimulus packages, have been almost exclusively along party lines.

And the American people are now almost as divided as elected officials.

According to a poll of 10,000 adults taken between January and March, 2014 by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 92% of Republicans are to the right of the average Democrat and 94% of Democrats are to the left of the average Republican.

The percentage of respondents with a highly negative view of the opposing party has doubled since 1994: 27% of Democrats and 36% of Republicans believe the policies of the other party are a threat to the well-being of the nation. For these folks, compromise means their side gets more of what it wants. The most politically polarized Americans are more actively involved in politics, the Pew study reveals, “amplifying the voices that are the least willing to see the parties meet each other halfway.”

And, since more and more Americans say they want to live in a place where their neighbors share their political views (a desire more widespread on the right than on the left) and tend to get their information about politics from partisan sources or “echo chambers,” the ideological chasm is not likely to be bridged anytime soon.

The inevitable midterm penalty

In midterm elections, the president’s party almost always loses seats, especially in the House of Representatives. The only exceptions to this pattern occurred in 1934, 1994, and 2002.

The most persuasive explanation of this phenomenon is that the higher turnout in presidential years includes large numbers of voters who are going to the polls principally to support the winning candidate and, while they are at it, congressional aspirants from the same party who otherwise would have lost. Two years later, however, these same voters stay home. This is the phenomenon that statisticians refer to as a “regression to the mean.”

Since the size of the midterm penalty often correlates with the approval rating of the president, the challenge the Democrats face is almost certainly greater than usual in 2014. If a Republican president as unpopular as Barack Obama were in office, political scientist Eric McGhee estimates, the Democrats would have a 67% chance of taking back the House of Representatives; under current circumstances McGhee’s forecasting model gives them a 1% chance of winning a majority of House seats.

Whoever ‘wins’, more of the same

It may well be, as many pundits now predict, that in the midterm election of 2014 a perfect storm will hit the Democrats, during which the Republicans hold the House, perhaps even gaining a few seats, and take control of the Senate. No matter what the outcome of this election, it seems clear that without fundamental changes in our political culture the “new normal” of American politics, polarization and paralysis, will remain in place – and may well intensify.