A new chapter in the long history of British programming on Australian television is about to be written, or rather, rewritten.

Last week, BBC Worldwide, the commercial arm of the BBC, and FremantleMedia Australia announced a partnership that promises to deliver Australian versions of some of the many entertainment formats in the BBC’s extensive program catalogue.

The deal has potentially significant ramifications for the partners and their parent organisations, for Australian audiences, and the production industry here.

There are several motivations behind the new partnership. At its heart is the extraordinary popularity of entertainment formats in Australia. Five of the top ten highest rating programs here so far this year have been formats, including Monday’s X Factor Grand Final which attracted over 3.5 million viewers.

Australasia remains the second largest export market for both BBC and UK television content. And yet only three local versions of BBC formats will have screened here by the end of this year – Dancing with the Stars (Seven Network), The Great Australian Bake-Off (Nine Network) and Coast (History Channel).

The new partnership is likely to change this situation dramatically. It brings together two of the key players in the television format business.

FremantleMedia has a long and impressive history in format development and reversioning. Its headline properties include The X Factor (over 25 versions around the world), Idol (over 40 international versions), and …’s Got Talent (over 50 versions).

BBC Worldwide distributes and licences content produced by the BBC and over 200 independent production companies. The BBC is one of the world’s major format developers. Its current successes include Dancing with the Stars (produced in over 40 territories), and The Great … Bake Off (sold to 11 territories in 2013). BBCWW also manages a portfolio of BBC branded channels which reach over 400 million homes around the world.

Australia is a key territory for both of the partners, and not only because Australians have an almost insatiable appetite for entertainment formats.

Earlier this year, BBCWW announced a major deal with Australian pay television provider Foxtel.

A new channel, BBC First, will be launched next year. It will screen first-run scripted drama and comedy from the British public service broadcaster. Like BBC HD, which at launch here in 2008 was the first high definition BBC channel broadcast outside the UK, and the (recently scrapped) global iPlayer catch-up service, the new channel will screen first in Australia before being rolled out around the world.

In 2007, BBCWW bought a stake in local production company Freehand (which developed the My Restaurant Rules format, and created the Australian version of Top Gear). This was BBCWW’s first investment in a production company.

BBCWW subsequently bought stakes in companies in the UK and a number of other territories, although many – including Freehand – have recently been sold off. The original Freehand deal came in the middle of a wave of international investment in Australian production companies in the mid-2000s.

FremantleMedia set the wave in motion. The company is owned by the RTL group which itself is part owned by the global media behemoth Bertelsmann. Its local subsidiary, FremantleMedia Australia, has been a major player here since its formation in 2006 following the merger of Grundy Television (producer of Neighbours and Wheel of Fortune, among many others) and the comedy producer and format developer CrackerJack. Alongside a slew of entertainment formats, FremantleMedia Australia produces the drama series Wentworth and Wonderland.

BBCWW is understandably anxious to exploit its intellectual property more extensively. Its production and distribution activities have become significant revenue sources for the BBC at a time when the UK public broadcaster is under pressure to cut its costs by 20 per cent over the next five years.

Last year, BBCWW generated over £1.5 billion in sales, and returned over £150 million to the BBC.This income to some extent offset the losses incurred from the BBC’s failed project to digitise its entire archive. The BBC has also come under financial pressure as well as attracting extensive public criticism in the UK for the massive payouts it has made to departing executives.

Many of these followed in the wake of a series of scandals including ongoing inquiries into pedophilia and sexual abuse, and a culture of bullying within the Corporation.

With a new director general, Lord Hall, at the helm, the BBC is desperately trying to set a new course. BBCWW, among other divisions, has been restructured under its new chief executive, Tim Davie. It has shifted from divisional to geographical reporting lines, with its seven markets grouped into what are claimed to be three “regional” businesses.

Somewhat confusingly, Australia (and New Zealand) have been grouped with the UK under a new managing director, Jon Penn. Penn joined BBCWW in April this year after a successful stint as CEO Asia Pacific at FremantleMedia.

The new arrangement makes clear commercial sense for both partners. FremantleMedia gains access to a huge number of pre-tested program formats. BBCWW stands to make substantial financial gains from the commissions that will result, without the costs of establishing its own local production entity.

And then there is the potential for additional commercial activity, including live events (along the lines of the Top Gear Festival) and merchandising.

The partnership should also be good news for the local production industry. Given its past and present successes, it is reasonable to assume that FremantleMedia will generate many new commissions from local broadcasters. These productions are in turn likely to generate considerable local employment opportunities at all levels.

What they will not do, however, is generate locally-held intellectual property. If, as seems likely given recent history, the BBC is using Australia as a testing ground for other territories, this means that there will not be the kind of financial returns to local producers that flow from international remakes of Australian-generated formats.

Australian viewers are likely to have even more opportunities to seek their fifteen minutes of fame. Entertainment formats tend to require large numbers of ordinary people, either as contestants or as live studio audiences. Audiences will also be familiar with some of the original programs, many of which have screened on both free-to-air and subscription television here.

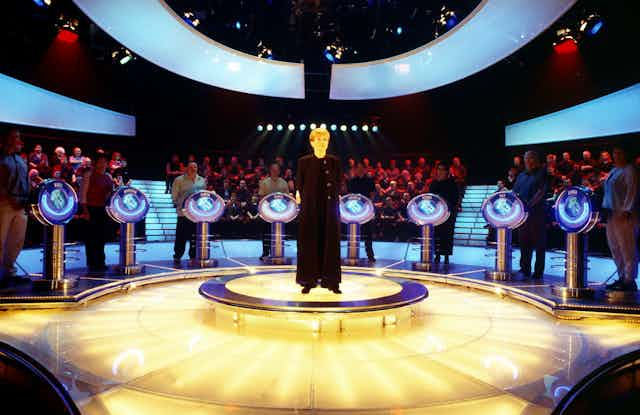

While it is yet to be seen which BBC programs will be recreated, when the partnership was announced special mention was made of the antique shows Bargain Hunt (currently screening on 7Two and Lifestyle) and Antiques Roadshow (Nine and Lifestyle), as well as the quiz shows Mastermind and The Weakest Link. The latter show was unsuccessfully remade by the Seven Network in 2001-02.

The partnership also covers new shows developed by the BBC, so it is possible that we might see a local version of the recently commissioned Let’s Get Ready to Tumble, a celebrities-do-gymnastics show. And yet the path from Dancing with the Stars (or Strictly Come Dancing, in its original British form) to Let’s Get Ready to Tumble may not be paved with gold, at least in Australia.

Other shows in the “celebrity reality” sub-genre have not fared well here. Celebrity Splash tanked earlier this year, while Dancing on Ice is better remembered for its celebrity casualties than its ratings. And does anyone remember Celebrity Circus?