The note Leonard Cohen wrote to his former lover Marianne Ihlen as she lay upon her death bed became a viral phenomenon after they both died in 2016. But Cohen’s last letter to Ihlen was not entirely what you read.

Ihlen had been hospitalised with leukaemia in Norway when a friend contacted Cohen to inform him of her impending death. He responded with the letter (sent as an email) within hours. Ihlen died several days later, on July 28th, having had this farewell message read to her. For a private communication, this letter soon became very public.

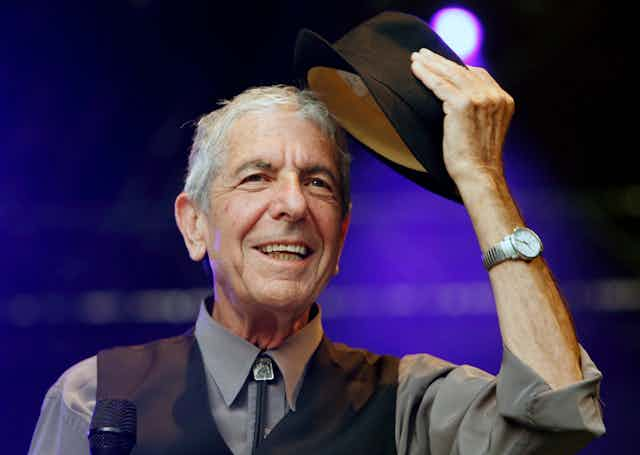

Already it is canonised, and not only among fans of the Canadian poet, singer and songwriter. It was recently included in a collection of correspondence, Written in History: Letters that Changed the World, edited by English historian Simon Sebag Montefiore.

Montefiore starts his introduction to the book with the declaration that, “Nothing beats the immediacy and authenticity of a letter.” But the history of the Cohen letter’s circulation shows how “authenticity” can be rendered questionable by those seeking to exploit its “immediacy”. It also highlights the myth-making around this writer-muse relationship that gathered fabled resonance after Cohen and Ihlen met on the Greek island of Hydra in 1960, although the relationship had all but run its course by the decade’s end.

Ihlen’s friend who brokered this final exchange with Cohen was film-maker Jan Christian Mollestad. Within days of Ihlen’s passing, Canada’s national English-language broadcaster, CBC radio, had tracked down Mollestad. An interview with him was posted on the station’s website, along with a truncated transcription, on August 5 2016.

In response to a question from the interviewer, Mollestad went on to “quote” Cohen’s letter in full.

Well Marianne it’s come to this time when we are really so old and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine.

And you know that I’ve always loved you for your beauty and your wisdom, but I don’t need to say anything more about that because you know all about that. But now, I just want to wish you a very good journey. Goodbye old friend. Endless love, see you down the road.

The text of this letter, as Mollestad recited it, was immediately picked up by other news outlets. The Guardian and Rolling Stone both ran the story of the letter on August 7th, repeating the CBC version in full.

Read more: Friday essay: a fresh perspective on Leonard Cohen and the island that inspired him

The letter’s instant notoriety was born not only of its gentle farewell to the soon-to-be departed Ihlen, but also because of the intimations of Cohen’s own demise. And its consumption was massively enabled by social media.

‘The syntax of love’

A follow-up article in the Guardian praised the letter’s “economy of words, the syntax of love, his ability to go straight to the only matter that matters – her death, his mortality, their love – is a thing of beauty and wisdom in itself.” It was a sentiment echoed by many.

On November 7 2016, Cohen died. The letter was immediately resurrected across multiple news and social media outlets. It was used now to focus on Cohen’s prediction that, “I will follow you very soon,” and his evocation, through the image of Ihlen’s reaching hand, of being drawn towards her in death.

Over the following months, the letter was read in “tributes” for the departed singer, frequently paired with a performance of So Long, Marianne from Cohen’s 1967 debut album. In November 2017, Adam Cohen, Leonard’s son, interpolated the letter into the lyrics of So Long, Marianne at a star-studded, first-anniversary tribute show in Montreal.

Cohen’s letter, now seemingly endorsed by his family, had become part of his canon. All good … except that the words used in it weren’t Cohen’s.

What happened?

Bypassing the abbreviated transcript and listening to the recorded version of the CBC interview with Mollestad is revealing. Journalist Rosemary Barton asks: “I know you don’t have it [the letter] in front of you, but I’m sure given it was written by Leonard Cohen you can remember part of it?”

In response, it is clear that Mollestad is paraphrasing. He stumbles a number of times, trying several phrases over in different forms as he struggles to accurately recall Cohen’s words. As he reaches the conclusion of the letter as he recalls it, he simply mumbles, “something like that”.

When the interview was transcribed for the CBC website some editorial “smoothing” of Mollestad’s recalled version of the letter was undertaken to remove his justifiable hesitations. In the process, more minor changes were made.

In his book, Montefiore resurrects what is likely an accurate copy of Cohen’s letter, with permission to use attributed to “The estate of Leonard Cohen”. Its differences are, understandably, considerable. It reads in full:

Dearest Marianne,

I’m just a little behind you, close enough to take your hand. This old body has given up, just as yours has too, and the eviction notice is on its way any day now.

I’ve never forgotten your love and your beauty. But you know that. I don’t have to say any more. Safe travels old friend. See you down the road. Love and gratitude. Leonard

Not only is the Mollestad/CBC version a full third longer, but in small but meaningful ways the intent of Cohen’s original was also altered.

Cohen’s “Dearest Marianne” strikes a different opening note to the resignation of “Well Marianne”. Mollestad has Ihlen reaching out (or back) for Cohen’s hand, whereas Cohen gives himself the possibility of reaching for hers; Mollestad’s introduced reference to Ihlen’s “wisdom” changes the inflection of the relationship between the two protagonists; and Cohen’s reference to the couple facing “eviction” from their bodies alters the constant gentleness and intimacy of Mollestad’s version.

Arguably Mollestad’s version is a little more pleasing in some of its phrasing, with “so close behind you” coming more easily than Cohen’s “just a little behind you”; and his reference to a “good journey” chiming more satisfactorily than Cohen’s “safe travels” with the shared closing salutation, “see you down the road”.

The Cohen letter’s circulation in its original form may change, ever so slightly, how the personal histories of Cohen and Ihlen are remembered. And this is a letter that has been changed by history, as journalists and social media commentators, feeding a voracious news-cycle, cast authenticity aside in the process.

Although the appearance of the Cohen letter in Montefiore’s volume appears to correct the record, it will be interesting to see which of the two versions survives.

It will likely be the one originally posted by the CBC. Not only is it far more widely known and available, but many people will probably find it more appealing and moving than the original.