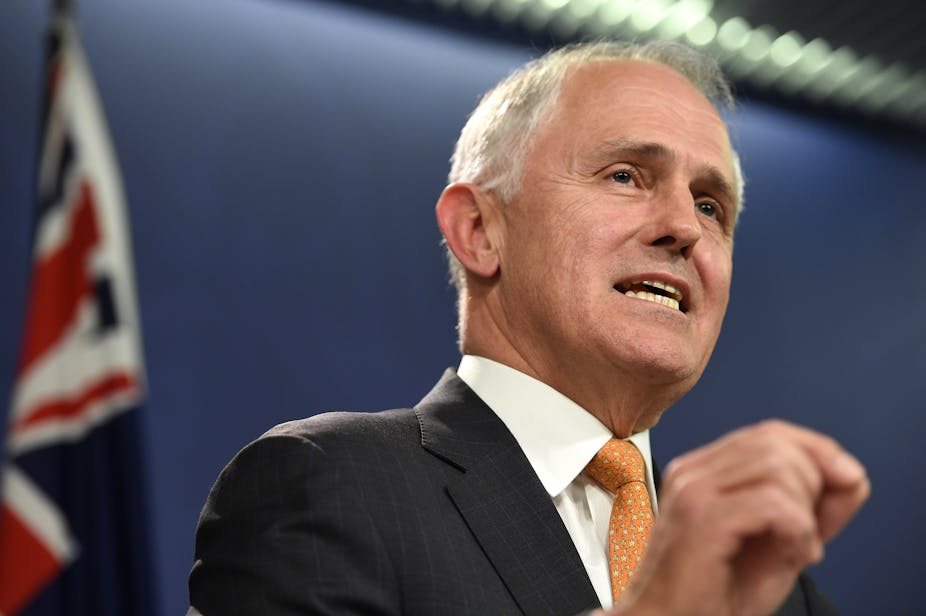

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull recently made a strong contribution to restoring a sense of dignity to Australia’s counter-radicalisation policies when he emphasised that “mutual respect” should be its key foundation.

This was a breath of fresh air after the divisive tones of his predecessor, Tony Abbott. It will help allow Australians to feel a sense of pride in the country’s undoubted counter-terrorism successes. Operation Pendennis in 2005 was the best of these.

But, as Turnbull prepares for a meeting this week of federal, state and territory agencies to discuss Australia’s approach to countering violent extremism, one would hope that he also promotes a fresh look at the best available research on what works and what doesn’t.

Radicalisation and terrorism are two separate beasts

Will Turnbull act on the findings of an Australian study published in 2015 that reports, in passing, disaffection in the Muslim community with the government use of the terms “radical” and “extremism”?

What will Turnbull make of the 2014 book, Traces of Terror, that found key communities perceive Australian counter-terrorism policies as tinged with racism?

Leading studies by international organisations such as the Club of Madrid do not give the same emphasis to counter-radicalisation as the Australian government does. That organisation has sponsored many reports on countering violent extremism. One of the most thorough and best deliberated may be a 2005 study, Addressing the Causes of Terrorism. The word radicalisation, or variations on it, appears only seven times in 50 pages, and even fewer times in each of two follow-on volumes.

Radicalisation and terrorism are two different phenomena – legally, politically, psychologically and morally. While a terrorist is by definition radicalised, the mere fact of being radicalised does not explain the transition to terrorism – a choice for violence.

In most scenarios, there are many “radicals” in any cause for each person who becomes a terrorist. A policy that screens radicals for terrorists is not workable or reliable, nor scientifically defensible. It will always record significant failures.

What Australia needs to do

Herein lies a policy implication for Australia. Why is it staking so much on counter-radicalisation? Even Turnbull said:

Preventing someone from becoming radicalised in the first place is the most effective defence against terrorism.

Counter-radicalisation is only one part of nearly 20 very distinct areas of policy to combat terrorism. It is probably not the most effective by a long shot. Other areas of policy that need appropriate public recognition and debate include intelligence, research, legislation, legal system (judges and prosecutors), law enforcement (police) and combating terrorist financing.

Turnbull’s statement that counter-radicalisation work is the best defence against terrorism begs the question of what policies – apart from that one – can be effective. The list is long. The government has invested heavily in some of them – especially intelligence – but not in most of them, such as the training of police investigators and court prosecutors for counter-terrorism cases.

In April 2015, an independent international evaluation of Australian policy on terrorist financing found a number of shortcomings. Not least of these was the lack of engagement by police forces with nationally available data to launch investigations of terrorist financing.

In the equally important area of legislation, the government’s approach has been consistently criticised by a range of professional associations, community leaders, experts, ethicists and the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor. The monitor’s 2014 annual report is a scathing indictment of a government that has all too often simply refused to address the security watchdog’s important concerns, or those of a well-meaning legal fraternity.

Has the government ever evaluated the success of its counter-radicalisation program (at a cost of around A$40 million) relative to other counter-terrorism measures? In February 2015, the Parliamentary Library reported that a promised evaluation of Australia’s programs in this area in 2012 did not appear to have been completed.

As an alternative narrative, the Australian government may want to consider an assessment that goes like this. The best way of preventing terrorism by new recruits is to capture and convict known terrorists. Failure to “capture and convict”, whether in Australia or overseas, is a gift to terrorist recruiters.

Until Australian security agencies can demonstrate more success in capturing and convicting terrorists, new recruits to terrorism in Australia will increase in number. Australia needs a powerful and sustained public campaign around its counter-terrorism successes more than it needs morally troubling and unscientific public discourse about youth radicalisation.