More than a year after the High Court’s decision in the “Palace letters” case, which said the queen’s correspondence with Governor-General Sir John Kerr is not “personal”, more letters have now been made public.

The letters between a further six governors-general and the queen have now been released to me, from Lord Casey in 1965 to Sir William Deane in 2001. Deane’s letters are being revealed here for the first time. In total, this is more than 2,000 pages, spanning 36 years and nine prime ministers.

These newly released letters cover some of the most important and memorable moments in Australian politics: the 1967 referendum on Aboriginal rights; the disappearance of Prime Minister Harold Holt and appointment of Prime Minister John McEwen; the election of Gough Whitlam in 1972; Whitlam’s double dissolution election in 1974 and Malcolm Fraser’s in 1983; the Australia Act; the High Court’s 1992 Mabo decision; and the 1999 republic referendum.

The breadth of correspondence gives us a rare opportunity to explore the changing nature of the vice-regal relationship over time.

The letters also provide a point of comparison with Kerr’s “sycophantic grovelling” and “stomach-churning” letters, as former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull describes them. Seen across the 36-year trajectory of this vice-regal correspondence, Kerr is even more clearly an outlier.

In just three and a half years, Kerr’s correspondence comprises as many pages as four governors-general (from Casey to Sir Ninian Stephen) put together.

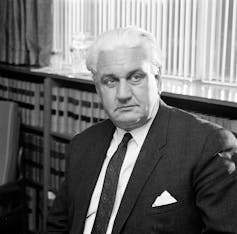

No other governor-general even comes close to the obsessive frequency of Kerr’s 116 lengthy letters. Casey wrote about 34 letters during his five-year term, Sir Paul Hasluck 37 in six years, and Stephen just 23 letters in six and a half years.

How much other governors-general shared with the queen

The correspondence of these seven governors-general spans 14 elections, two of which, the 1974 and 1983 double dissolutions, had the potential to cause controversy for the governor-general in accepting the prime minister’s advice to call them.

Similarly, Whitlam’s formation of the “duumvirate” (two-man ministry) in 1972 was an unprecedented situation for his first governor-general, Hasluck. This was a two-week ministry made up of Whitlam, with 13 portfolios, and his deputy Lance Barnard with 14, until the final number of seats had been determined.

It is notable neither Hasluck in 1974 nor Stephen in 1983 discussed their options or intentions with the palace before accepting the prime minister’s advice.

There is no parallel in the correspondence of other governors-general with Kerr’s discussions with the queen, her private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, and Prince Charles, regarding the possible dismissal of the Whitlam government and the use of the reserve powers (against ministerial advice) to do so.

Read more: At long last, we can tear open the queen's secret letters with Australia's governors-general

It is a hallmark of these letters that, unlike Kerr, the governors-general report back to the queen after these events they describe.

Casey informs the queen after he has appointed McEwen as acting prime minister following Holt’s disappearance, for example, while Hasluck writes to Charteris ten days after accepting Whitlam’s advice to call the 1974 double dissolution.

Stephen also writes to the queen two weeks after accepting Fraser’s contentious advice to call the 1983 double dissolution. Eighteen months later, he follows up with a letter on the intricacies of the double dissolution provision in section 57 of the Constitution and the discretionary power it confers to the governor-general.

In fact, it is Charteris who writes to Hasluck prior to the 1974 double dissolution hoping for further information, telling Hasluck he was “not uninterested at the moment in anything to do with the prerogative of Dissolution!”. Hasluck ignores this invitation to discuss the prerogative.

These post-facto comments are in no way comparable to Kerr’s extensive discussions with Charteris over several months about the governor-general’s reserve powers and the possible dismissal of the prime minister. There is simply no equivalent to what Kerr calls “Charteris’s advice to me on dismissal”.

Cowen’s streak of assertiveness

Similar to Stephen after him, Governor-General Zelman Cowen is assertive and independent, at times disputing aspects of the queen’s letters and instructing the private secretary on matters of law.

In a letter to the private secretary Sir Philip Moore in December 1978, Cowen corrects erroneous press reports claiming if Whitlam had sought Kerr’s recall as governor-general in 1975, the queen would not have acted on the advice of the Australian prime minister and would instead have acted on the advice of her UK ministers.

Quoting his own book on the governor-general, Sir Isaac Isaacs, Cowen tells Moore, “it is inappropriate that UK ministers should be concerned in the appointment of a Governor-General” and it is “surely inappropriate that the Monarch should act otherwise” than on the Australian prime minister’s advice.

Cowen also strongly disagrees with Moore on the 1978 appointment of Kerr as Australia’s ambassador to UNESCO – and on the appointment of any former governor-general to paid public office. He said,

I have grave doubts about this […] any suggestion (or appearance of a suggestion) that a Governor General might be influenced in his conduct by such expectations is damaging.

‘I get no joy from these assessments’

The suggestion other governors-general show the same “obsequious deference” as Kerr in these letters is unsustainable.

Bill Hayden follows Stephen as governor-general in 1989, towards the end of Bob Hawke’s term as prime minister. Clearly still bristling at having lost the Labor leadership to Hawke so close to the 1983 election, Hayden interprets his “duty” in writing to the queen as providing “a candid and fair, if at times harsh” assessment of political figures, many of whom are his former colleagues.

His reports are dry, lengthy descriptions of the political, social and economic situation in Australia. He invariably sees large-scale problems for Hawke, saying his “extraordinary popularity defies reasoned understanding”.

Hayden is an astute and detailed observer, correct in many of his forecasts, and yet throughout his letters there is little sense of what he does in his daily routine as governor-general.

Where others send copies of articles, speeches and reports on things like engagements at Government House, Hayden’s letters seem more removed from everyday vice-regal life. They appear increasingly forced — particularly after Paul Keating defeats Hawke in a 1991 leadership spill to become prime minister — and his letters become less frequent.

There is a poignancy in Hayden’s final lament to the queen about his “harsh judgment” of Keating. “I get no joy from these assessments”, he tells the queen, adding he has done so only as “a matter of duty to you”. Keating is a personal friend, “an admirable person”, he insists, seeming to regret what he has written.

It adds a human element to the absurdity of the arcane secret ritual of vice-regal correspondence.

Read more: Jenny Hocking: why my battle for access to the 'Palace letters' should matter to all Australians

Deane strikes a tone of equals

With Sir William Deane following Hayden as governor-general, the transition from the supine deferential genuflections of Kerr to an exchange of letters between equals is complete.

Deane passes much of the routine reporting on plans for royal visits, election results and press clippings on the republic debate to the official secretary, who writes to the queen’s private secretary. Deane himself, for the most part, writes directly to the queen – “Your Majesty, Ma’am” – rather than her private secretary.

This assertion of vice-regal equivalence is a statement in itself, not so much of Deane’s self-assured independence, but Australia’s.

At the same time, Deane informs the queen he will be sending copies of their correspondence to the prime minister, effectively ending the secrecy of vice-regal correspondence from the Australian government, which had so plagued Whitlam.

This dramatic shift follows an unusual exchange with the queen’s private secretary, Sir Robert Fellowes, early in Deane’s term.

In the context of the burgeoning constitutional debate ahead of the republic referendum, Fellowes asks the official secretary, Douglas Sturkey, whether there was anything members of the royal family could do “in the interests of the monarchical system”. He raises the timing of a possible royal visit by either Prince Charles or the queen.

Sturkey tells Deane he finds Fellowes’ suggestion “curious”:

I cannot seriously believe that Sir Robert Fellowes is proposing an active (and unprecedented) role for the monarchy in public constitutional debate.

Deane tells him not to do anything about it, and the letter goes unanswered for two months.

These letters are a unique window on an evolving vice-regal relationship and an exceptional addition to our history. It is immensely disappointing, therefore, the National Archives has made numerous redactions throughout them.

Worse, Buckingham Palace was consulted on those redactions. The former director-general of the archives, David Fricker, conceded last year that the archives was consulting “the Royal Household” on redactions, despite the High Court’s decision overturning the queen’s embargo over their release.

After a four-year legal action to secure the release of these letters, the least the archives could do is to finally let us see them in full.