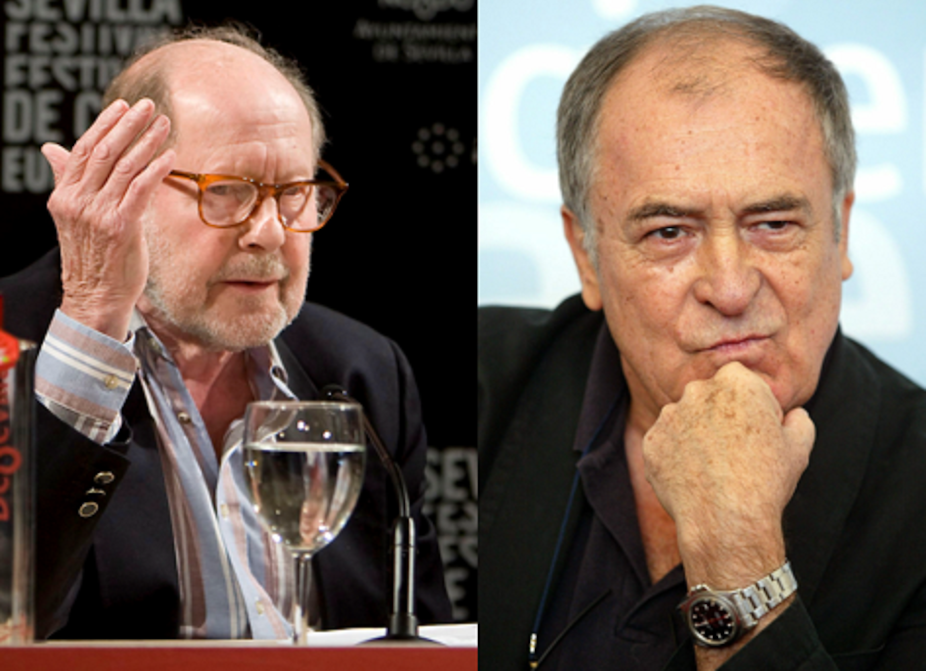

Deaths in close proximity have a tendency to invite comparisons. We may look for connections between two otherwise unrelated figures whose passing in quick succession makes them final bedfellows. Often any such links are purely arbitrary, but with Nicolas Roeg (1928-2018) and Bernardo Bertolucci (1941-2018), who died on November 23 and 26 respectively, there is a certain logic to putting them in harness, even though they never worked together. Cultural commentators have already begun to do so, and with good reason.

Both filmmakers had diverse careers stretching over half a century, but as directors they were giants of the 1970s. In particular, both were at the forefront of the liberalised depiction of sex following the relaxation of censorship restrictions in both the US and the UK.

Roeg’s Performance (1970, co-directed with Donald Cammell) and Bad Timing (1980) and Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970) and 1900 (made in 1976), among others, all featured notably explicit sexuality – but their key works in this regard were released almost concurrently.

Famous sex scenes

A visitor to the West End of London in late 1973 could have found the directors’ seminal works playing first run in different cinemas, both with “X” ratings. Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972) scandalised morality campaigners with its brutally casual passion between lovers (Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider) who don’t even know each other’s names.

Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973) is a horror movie, but midway through there’s a tenderly sensual scene of lovemaking between husband and wife (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie) so intense that it led many viewers to believe that the sex might have been performed for real.

That rumour has long since been put to bed (no pun intended). But Last Tango was different. The question of what actually happened on set was raised in a 2007 interview with Schneider, in which she claimed to “have felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci”. Apparently intended metaphorically, this comment has since been taken literally.

In a 2013 interview (not widely seen until 2016) the director admitted that he and Brando had together conspired to introduce butter as a lubricant in an act of simulated sodomy, without telling the actress until immediately beforehand in order to produce an authentic reaction on camera. In a passage often omitted from subsequent accounts of the incident, Schneider clarified that “even though what Marlon was doing wasn’t real, I was crying real tears”.

According to Schneider, it was Brando’s idea to use the butter, but it was Bertolucci she blamed for not telling her – she appeared to have forgiven the actor but not the director.

Read more: Why we should no longer consider Last Tango in Paris 'a classic'

In the age of #MeToo, this particular controversy has not abated and it is likely to blight Bertolucci’s memory. No such real-life scandal has attached itself to Roeg, despite the often-appalled reactions to some of his films, even by their own distributors. But there are other reasons to link these two filmmakers besides the obvious one of sexual representation.

Odd men out

Some years ago, attempting to explain Roeg’s creative inactivity (he made only one feature film after 1995), an industry professional earnestly told me that cinema is not a medium for intellectuals – at least not in its commercial form. That, it seems, was what made Roeg such an odd man out in British filmmaking after his 1970s heyday and why after a while he seemed almost unemployable unless he suppressed his individuality. Yet in several of his most characteristic films he married a dazzling visual surface and a self-consciously dense approach to storytelling with wide audience appeal.

As a product of the so-called European “art” cinema, Bertolucci was virtually obliged to be an intellectual, a vocation he had no trouble in fulfilling. And yet, like Roeg, the Italian auteur was also able to cross over into the mainstream. Last Tango was financed and released by United Artists, a major Hollywood studio, and proved a huge hit.

Other US majors backed some of his later ventures in the hope of similar success. Bertolucci’s most conventionally prestigious film, the multi-Oscared The Last Emperor (1987), is that rare beast, a cerebral epic.

The Last Emperor was one of six pictures Bertolucci made with producer Jeremy Thomas, whose white-bread family background (he was the son of “Doctor” series director Ralph Thomas and the nephew of “Carry On” helmsman Gerald Thomas) belies the offbeat, ambitious projects he has supported as an independent producer.

It’s no coincidence that Thomas also produced three films by Roeg, whom he once called “the greatest living British director”, beginning with Bad Timing. Bertolucci he called one of “the most significant filmmakers that ever walked the Earth”.

Nicolas Roeg and Bernardo Bertolucci challenged the commonly drawn distinctions between mainstream and independent, art and commerce, accessibility and difficulty. It’s their achievement in reconciling these apparent opposites, and the sheer brilliance of their best work, that should survive them, not the controversies their work engendered – whether on or off the screen.