In the past four weeks, a major political earthquake seems to have hit the Middle East, where three key regional constituencies: Iran, Qatar and Egypt, experienced more or less unexpected changes of leadership. New leaders are always welcomed with great expectations, by both domestic observers and the international community at large. In this instance, however, there is not much room for optimism, as the installation of new leaders can be seen as a merely cosmetic development in the evolution of incumbent regimes.

The substance – beyond the clamour that recent events had inevitably caused – is that leadership transitions are not expected to bring to the fore any substantial modification to local dynamics of government/opposition interaction, nor are they likely to usher in a new era of economic policy-making.

Iran: conservative reformer

The election of Hassan Rowhani to the presidency of the Islamic Republic of Iran opened this season of apparent change in the Middle East. Too quickly labelled a “reformer”, Rowhani sits at the least intransigent end of the current Iranian political spectrum. His rhetoric – and hopefully his decision-making style – are expected to sensibly differ from the aggressive international persona and chaotic government methods of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Rowhani will have the mission of toning down the rhetoric of the Iranian regime, increasing its international appeal while facing the dramatic economic crisis triggered by the international sanctions imposed on Iran. It is only in this restrictive sense that Rowhani’s election represents an element of discontinuity in the Iranian political continuum.

Iran’s new president won’t be in a position to influence the regime to encourage the emergence of political pluralism. This sort of issue remains the prerogative of the office of the Supreme Leader. Ali Khamenei, with the support of the many non-elected bodies active within Iran’s institutional machinery, has consistently maintained very conservative views about the emergence of genuine pluralism in the Islamic Republic.

To some extent, Rouhani’s key strength is that he came to power after a free and fair vote sustained by a high turnover. And while he was on the list of candidates approved by the regime, he was not among their preferred choices.

Popular legitimacy, on the other hand, is not a defining feature of the other instances of leadership change examined here.

Qatar: new blood, old family

In the case of Qatar, the house of Al Thani finalised a long-term process of leadership change through the customary channel of intra-familial appointment, which represents the norm in most Gulf polities. The elevation to power of Tamim bin Hamad al Thani is designed to inject new blood in Qatar’s monarchy, while maintaining the international prominence that the country acquired during the (relatively) long rule of Hamad bin Khalifa.

Remarkably, the transition at the top of the Qatari leadership is expected to bring about some substantive restyling of the élite supporting Sheikh Tamim. If it does eventuate, this will indeed represent a significant development in today’s Middle East, where new leaders – as the cases of Iran and Egypt demonstrate – continued to be surrounded, advised and, more often, challenged by remnants of prior regimes.

Policy discontinuity, on the other hand, is not one of the features likely to emerge in the early stages of the rule of Sheikh Tamin, who is expected to adhere to the course traced by his father.

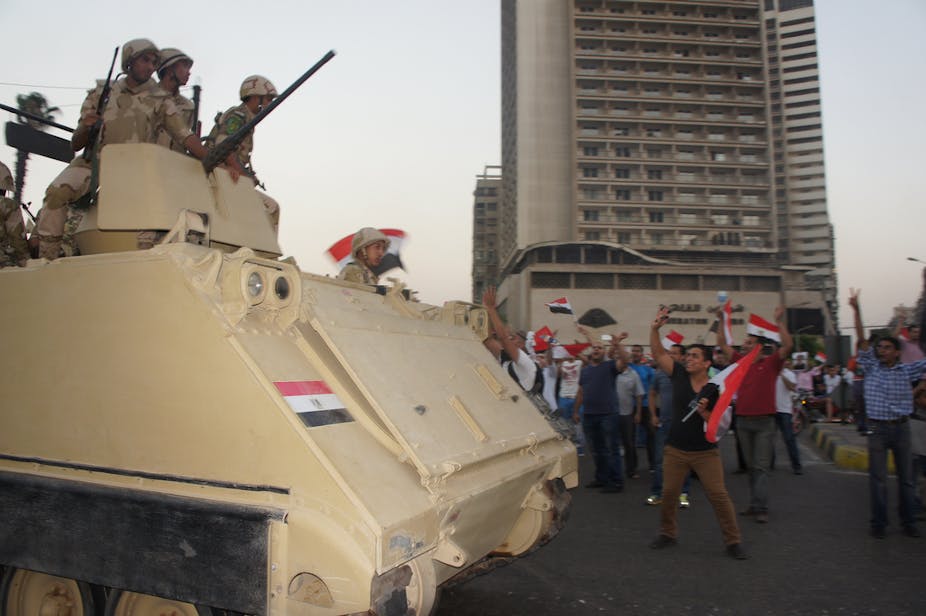

Egypt: power structures under stress

The complex relation between a new leader and the prior regime is at the very core of the current Egyptian power struggle, which has now become the most intractable political issue in Middle Eastern politics. It is virtually impossible to disentangle the very intricate linkages connecting the Muslim Brotherhood, the military and the protest movement Tamarod.

The military has been a central force throughout the history of modern Egypt, particularly in the republican era; it led the ‘post-revolution transition’ for no less than 18 months and has now returned at the epicentre of Egyptian politics. The Brotherhood – which ruled Egypt in the last 12 months – can hardly be considered a thoroughly anti-systemic force, as it often engaged with the prior regime in deals to acquire a monopolistic position in the opposition field. Tamarod, at the same time, features a similar combination of old and new actors, as it flags its direct links with the January 25 revolution while its membership is being uncomfortably infiltrated by remnants of the Mubarak regime.

A complex political conundrum is to be faced by whatever force emerges victorious from the power struggle initiated by the coup/non-coup of July 3 2013. Given the structural circumstances of the Egyptian “transition”, the next Egyptian president – if we ever get to elections – will be forced to forge alliances with actors in a way or another entrenched in the political life of the Mubarak era, making arduous (if not impossible) the establishment of a political system representing a clear break with the past.

Where will such a regime draw its legitimacy? This is a very complex question, particularly when asked within a political arena where the legitimacy of democratic elections has been reduced to “ballot-ocracy” by popular demand.

And this remains, to my mind, the critical issue currently at stake in the Middle East. No political system in the region has so far been able to establish a definite, smooth procedure for leadership transitions leading to meaningful political change. Change at the helm has always been the result of unpredictable circumstances (the incumbent’s death) or political violence (coups, revolution, civil war).

In Qatar, hereditary succession has ensured stability, but has failed to take into account the population’s will. In Iran - and through the region - the electoral institution has been made irrelevant by constitutional design. While in Egypt, as we saw last week, elections have been over-ruled by popular impulses.

Élites in the region need to address this question with some urgency, otherwise traumatic political events will remain the only catalyst for the emergence of qualitative change in governance practices and economic decision-making in the Middle East.