Have you ever actually read an app’s privacy policy before clicking to accept the terms? What about reading the privacy policy for the website you visit most often? Have you ever read or even noticed the privacy policy posted in your doctor’s waiting room or your bank’s annual privacy notice when you receive it in the mail?

No? You’re not alone. Most people don’t read them.

People are confronted with terms of service agreements and privacy policies all the time. Regulations requiring these notices aim to ensure that consumers can make informed decisions, but current privacy policies miss the mark. They are surprisingly ineffective at informing consumers, as Rebecca Balebako, Lorrie Cranor and I analyze in a recently published article.

In 2008 a study estimated that it would take 244 hours a year for the typical American internet user to read the privacy policies of all websites he or she visits – and that was before everyone carried smartphones with dozens of apps, before cloud services and before smart home technologies. With our research, my colleagues and I propose a better way to make clearer privacy policies that are easier to follow.

Hard to find, read and comprehend

Even people who do read privacy policies struggle to understand them, because they often require college-level reading skills. Privacy policies frequently cover multiple services offered by a company, resulting in vague statements that make it difficult to find concrete information on what personal information is collected, how it is used and with whom it is shared.

For example, Google’s privacy policy states “We collect information about the services that you use and how you use them, like when you watch a video on YouTube, visit a website that uses our advertising services, or view and interact with our ads and content.” Then it goes on to list examples of information that may be collected. What exactly is collected about users when they use a specific Google product remains unclear.

Privacy policies are also increasingly posted separately from users’ interactions with a system. For instance, websites link to policies at the bottom of pages, mobile apps link to policies in the app store and the privacy policy of your smart speaker or fitness tracker is likely posted somewhere on the company’s website.

Few privacy policies provide consumers with any choices besides not using the service at all. Companies may also change their privacy policies anytime. Not accepting the updated policy – if consumers are even asked to acknowledge the change – may stop your gadget from working or result in termination of the account.

Different purposes

A fundamental issue is that privacy policies serve different functions for consumers, companies and regulators. Companies use a privacy policy to demonstrate compliance with legal and regulatory notice requirements, and to limit liability. Regulators in turn use privacy policies to investigate and enforce compliance with regulations. Consumers’ need for meaningful information they can use to make choices regarding their privacy is thereby often neglected.

As a result, academics, regulators and governments have called for more usable privacy notices and solutions. For instance, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, which takes effect in May 2018, imposes strict requirements on privacy notices. Notices must be in “concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language.” Most privacy notices today do not meet these requirements.

Focusing on the consumer

The key to turning privacy notices into something useful for consumers is to rethink their purpose. A company’s policy might show compliance with the regulations the firm is bound to follow, but remains impenetrable to a regular reader.

The starting point for developing consumer-friendly privacy notices is to make them relevant to the user’s activity, understandable and actionable. As part of the Usable Privacy Policy Project, my colleagues and I developed a way to make privacy notices more effective.

The first principle is to break up the documents into smaller chunks and deliver them at times that are appropriate for users. Right now, a single multi-page policy might have many sections and paragraphs, each relevant to different services and activities. Yet people who are just casually browsing a website need only a little bit of information about how the site handles their IP addresses, if what they look at is shared with advertisers and if they can opt out of interest-based ads. Those people doesn’t need to know about many other things listed in all-encompassing policies, like the rules associated with subscribing to the site’s email newsletter, nor how the site handles personal or financial information belonging to people who make purchases or donations on the site.

When a person does decide to sign up for email updates or pay for a service through the site, then an additional short privacy notice could tell her the additional information she needs to know. These shorter documents should also offer users meaningful choices about what they want a company to do – or not do – with their data. For instance, a new subscriber might be allowed to choose whether the company can share his email address or other contact information with outside marketing companies by clicking a check box.

Understanding users’ expectations

Notices can be made even simpler if they focus particularly on unexpected or surprising types of data collection or sharing. For instance, in another study, we learned that most people know their fitness tracker counts steps – so they didn’t really need a privacy notice to tell them that. But they did not expect their data to be collected, aggregated and shared with third parties. Customers should be asked for permission to do this, and allowed to restrict sharing or opt out entirely.

Most importantly, companies should test new privacy notices with users, to ensure final versions are understandable and not misleading, and that offered choices are meaningful.

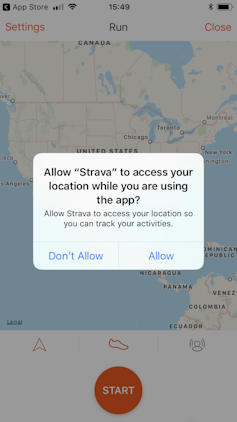

These shorter consumer-friendly privacy notices can easily coexist with traditional privacy policies. This is already starting to happen on mobile devices. Apple and Google, as the two largest smartphone platform providers, introduced just-in-time permission dialogues in 2008 and 2015, respectively. For instance, when a mobile app wants to access the phone’s location or contacts, the phone gives the user the option to say “No.”

Systems like this give consumers usable information and real choices. And they encourage app developers to communicate better with users about privacy. If we can expand this smartphone model to other uses, then everyone could have privacy policies that are clear, easy to understand and with real meaning for both users and software designers.