“I have striven to give a clear, true, and balanced picture”, wrote Nora Waln in the account of her years in the Third Reich.

An American journalist, she had moved there from China with her musician husband in 1934. They spent the next four years exploring Germany, Austria, and then Czechoslovakia, mixing with the “cultured classes”, and soaking up the music scene.

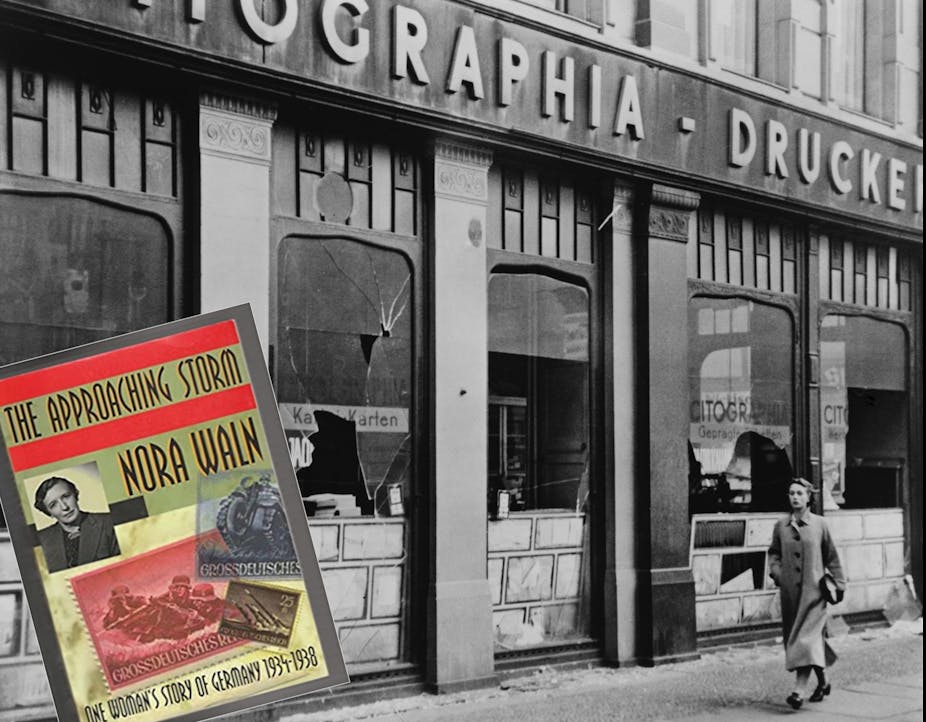

A few months before Kristallnacht – the Nazi-led night of anti-Jewish pogroms on November 9 1938, the Walns left Germany for England. There, the following year, Nora published her memoir of the period, Reaching for the Stars (reiussed in 1992 as The Approaching Storm: One Woman’s Story of Germany, 1934-1938). Waln’s approach seems shocking today, as she insists on seeing both the good and bad in the people around her in these early years of the Nazi regime. She was determined not to write off a country she loved, but was deeply shaken by its political trajectory.

Her memoir presents a broad range of sources and people, and her voice is rarely critical. Some subtle critiques emerge in moments of contrast and irony, though. For example, a countryside Christmas scene in 1934 shows the early nature of Nazi antisemitism, as nonsensical as it was pernicious. She hears carollers singing “Freu dich, o Israel” (Rejoice, oh Israel), but also records that “at the entrance and exit of every village, and sometimes before houses, stood a sign against the Jews”.

She reports on the suffering of Jews made to lose their jobs and homes (though not yet deported), alongside stories of loved ones sent to concentration camps for opposing Nazi ideas. There are stories of denunciations by neighbours, tragic suicides and one account of a missing husband returned to his wife as ashes in a cigar box, “marked with a swastika, and the word "traitor” before her husband’s name".

Common ground

Waln’s account does not separate the sufferers of Nazi oppression into Jews and non-Jews (“a distinction in tragedy of which I did not see the point”). She also refuses to demonise the Germans that she meets – whether they supported the National Socialists or not. On the contrary, she travels widely in order to understand the Nazi phenomenon better:

It had become imperative that I know who were Nazi, and why […] I had to learn these things by actual acquaintance with National Socialists.

Waln forged a number of close friendships on her travels. One example is an aristocratic family of foresters on the Wiegersen estate in Lower Saxony, who shared her deep love for trees. Remembering how she was welcomed into the heart of the family, she reflects: “In such ways only will humanity get past the false barriers of nationalism which have so corrupted human society.”

Her commitment to finding common ground with everyone she met sprang from her Quaker faith, seeking to recognise that there is “that of God in everyone”. But her memoir makes for uncomfortable reading at times, for example, when she remembers being pleased to hear that Hitler had liked her first book: “To write clearly is not easy. I am thrilled when I satisfy a reader.”

Writing after Kristallnacht (but before the world knew about the Final Solution), she seems to pre-empt accusations that she had been complicit in immoral Nazi policies: “I may be particularly stupid, but it never occurred to me when in Germany that I should continuously criticise the Nazis lest my silence be taken as a sign that I approved of all their activities.” After resisting the urge to categorise the Germans as either “good” or “bad” people for so long, the internal logic of this statement suggests that Waln was finally becoming prey to a kind of either/or thinking – either you oppose the regime constantly or you are complicit with its every policy.

Culture war

Waln’s statement raises serious questions today, not only because we know the full extent of Nazi atrocities, but also as we navigate our own current “culture war”. In the heated discussion of contemporary issues such as Britain’s imperial legacy, immigration policy, and justice for women and transgender people, we frequently hear that “silence is violence”. Does Waln’s memoir reinforce this message?

In some ways her nuanced approach is admirable. Waln tried to understand the historical and psychological impulses that led some Germans to choose the Nazi culture of domination. She also understood the terrible fear which made opposition impossible for so many. In this way, her memoir resists the rigid “victim/perpetrator” binary that has structured post-war discussions of the Third Reich and Holocaust and offers a more humane view of Germany’s tragic slide into totalitarianism.

But Waln was later compelled to resist the Nazis more directly. According to her obituary in the New York Times, she sent a copy of her memoir to the Nazi police chief Heinrich Himmler with an “insolent” inscription. In retaliation, he arrested seven of her friends’ children. Waln then offered herself as a hostage for their release. When Himmler offered to release the children if she would limit her writing on Germany to “romantic novels”, she refused. “If you make a bargain like that, God takes away the power to write. If you don’t tell the truth you lose your talent”, she wrote.

Waln may have been slow to speak out at first, but she ultimately refused to compromise with Nazism. Her admission in Reaching for the Stars that she could have acted sooner is a timely reminder to highlight injustice whenever we see it today. Perhaps, though, like Waln, we can do so in a way that resists the polarising approach of “us” and “them”.