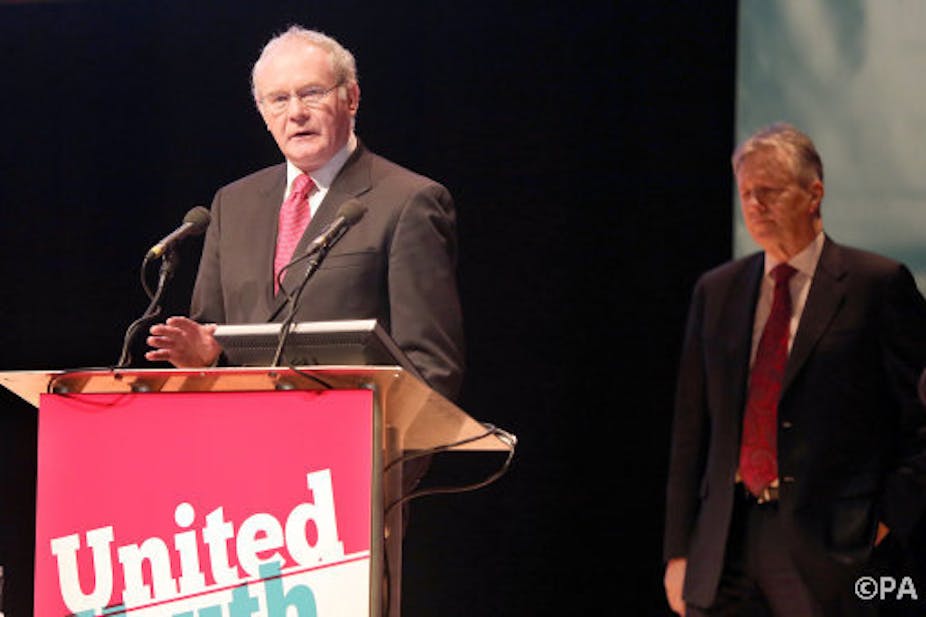

Northern Ireland’s first minister, Peter Robinson, threatened to resign over the issue of secret pardons granted to IRA fugitives, referred to as “on the runs” (OTRs), during the negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement. Robinson maintains that he knew nothing of such deals. David Cameron, no doubt in an attempt to placate Robinson, has announced a judicial review of the secret pardons, but the scheme itself, agreed as part of the peace process, will remain intact. Amid the outcry surrounding it, a number of questions arise – and despite the appearance of secrecy and chaos, their answers are largely to be found in the public domain.

The deal that led to 187 letters sent to OTRs telling them they were no longer being pursued was not done entirely behind closed doors, as Robinson and the former first minister David Trimble have claimed. A good deal of it was done in plain view, and it was covered in the media at the time.

In May 2000, as the negotiations at Hillsborough Castle led to an agreement on IRA disarmament, the British government gave further assurances to Sinn Fein that the situation of the OTRs would be addressed. In a letter to Gerry Adams, Tony Blair outlined the intended process:

I can confirm that if you can provide details of a number of cases involving people ‘on the run’ we will arrange for them to be considered by the attorney general, consulting the director of public prosecutions and the police, as appropriate with a view to giving a response within a month if at all possible.

Loyalists had also given their list of OTRs to the British government. According to “Plum” Smyth of the Progressive Unionist Party, Mo Mowlam gave assurances at a formal meeting at Stormont that there would be no legal pursuit of anybody wanted for offences committed before 1998, whether they be Loyalists, Republicans or members of the security forces.

Not everyone was happy about this. In June 2000, the attorney general wrote to then-secretary of state Peter Mandelson, expressing his concern:

The exercise that is being undertaken has the capacity of severely undermining confidence in the criminal justice system … and I am not persuaded that some unquantifiable benefit to the peace process can be a proper basis for a decision based on the public interest.

In spite of this, in January 2001, Tony Blair wrote to Sinn Fein"

The government recognises the difficulty in respect of those people against whom there are outstanding prosecutions … The government is committed to dealing with the difficulty as soon as possible, so that those who, if they were convicted would be eligible under the early release scheme are no longer pursued.“

The following January, Sinn Fein put forward John Anthony Downey as one of the OTRs.

In the 2001 Weston Park negotiations, the Irish and British governments agreed to introduce legislation to resolve the situation. Blair and Ahern subsequently wrote to all Northern Irish party leaders, informing them that the governments had agreed the elements of a package, and included a statement on OTRs:

Both governments also recognise that there is an issue to be addressed … about supporters of organisations now on cease-fire against whom there are outstanding prosecutions, and in some cases extradition proceedings … The governments … will, as soon as possible, and in any event before the end of the year, take such steps as are necessary in their jurisdictions to resolve this difficulty so that those concerned are no longer pursued.

It was not until November 2005 that the British government introduced the Northern Ireland Offences Bill, which proposed to give those eligible under the scheme a certificate that would exempt them from arrest. The bill failed to attract the support of the house. Nonetheless, Tony Blair wrote confidentially to Gerry Adams in December 2006: "I have always believed that the position of these OTRs is an anomaly which needs to be addressed. Before I leave office I am committed to finding a scheme which will resolve all the remaining cases.”

He assured Adams that the government would no longer seek the extradition of those who had escaped from prison and that he was expediting the existing administrative procedures to resolve all cases.

Operation Rapid

In early 2007, Operation Rapid was put in place by the Police Service of Northern Ireland. It was designed to review the cases of people “wanted” in connection with Troubles-related offences committed before 10 April 1998 and to determine what basis (if any) the police had for arresting them.

Downey’s case was reviewed as part of the operation and, in October 2009, an internal police report on him read:

Status reviewed by Op Rapid and assessed as “not currently wanted” by PSNI. He is, however, alerted on PNC as wanted for murder 20/07/82 (Hyde Park).

Due to what is claimed to have been an error, the PSNI did not alert the Department of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland or anyone else to the fact that Downey was wanted by Metropolitan Police in relation to the Hyde Park bombing. Downey was issued with a letter providing an assurance that he was not wanted for arrest, questioning or prosecution, and it was this letter that led to the collapse of his trial. But was this an error, or is there some secret system of pardon in operation?

The fact is that pardons for other IRA members have been in the public domain since an alleged deal with Sinn Fein about the use of the Royal Prerogative of Mercy (RPM) emerged during the trial of Gerry McGeough in April 2010. McGeough’s lawyers produced a document showing that dozens of OTRs had been told they were free to return to Northern Ireland, and argued that it was “incontrovertible evidence that (Royal) pardons were granted”. However, the judge found no evidence “that there is some form of deal between Sinn Fein and the government to prevent the exercise of the RPM in Mr McGeough’s favour”, and McGeough was subsequently jailed.

So what is news to the first minister and his DUP colleagues? The issue has been public for some time, and the Downey case is not the only one to have occasioned Unionist outrage. Why the furore now?

The DUP is in government with Sinn Fein, and is vulnerable to accusations of being too soft on the IRA; the hardline Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) and Justice for IRA Victims campaigners can turn any evidence of “softness” into political capital. Competition will be fierce in the European and local elections, and the DUP’s fear of losing further ground is driving them to a hard line. A split unionist vote, together with a changing demographic balance between Unionists and Nationalists, could see Sinn Fein emerge as the largest party. And that would be ignominious indeed.

This latest “crisis” in Northern Ireland has an air of theatricality about it. Elections encourage grandstanding and political posturing from all politicians, and Northern Ireland’s politicians are no less susceptible. The assembly might not be the smoothly-functioning democratic body one would wish, but it has managed to function these past few years; the political parties have settled into routines, and have basic working relationships with one another.

While it might tempt fate to say that they will continue to operate on this basis in spite of this latest storm, the indications are that they are merely beginning the fierce battle for the hardliners in the election, rather than moving towards the demise of the assembly. While politicians may speak about victims’ rights and desire for justice, this latest controversy is more about the battle for political power and forthcoming elections.