Despite increased awareness of autism and the impact it can have on people’s lives, many autistic people continue to struggle against misleading stereotypes.

Being autistic, for example, doesn’t automatically make you a “human calculator” or a “living Google” – despite what some people may think. And it also doesn’t mean you can’t grasp fiction or have a love of novels.

I’m an autistic lecturer in English and creative writing. Literature is my way into the world. It helps me to better understand people –- including myself. Plus, in novels and poems, words are freed from the weight of body language.

But according to stereotypes (and worse, expectations) around autism, I should not be able to grasp fiction –- let alone lecture or publish papers on it. Autistic people are supposedly good at STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, maths), not the arts.

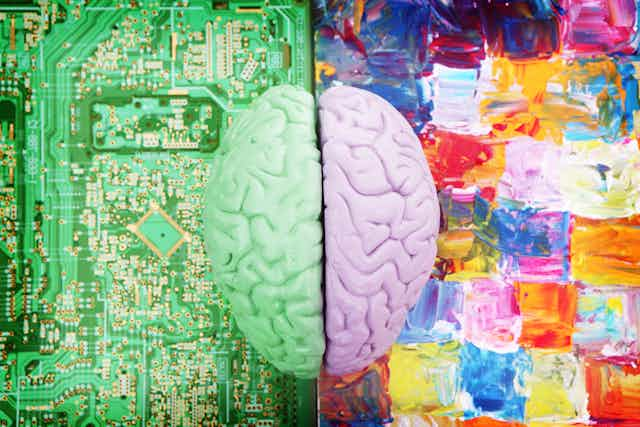

‘Minds wired for science’

For more than 20 years, the University of Cambridge’s Autism Research Centre has proclaimed that autism is linked with “minds wired for science” – which can be taken to mean minds not “wired” for creative or critical thinking. The association of STEM subjects with autism has been widely popularised by the centre’s director, Simon Baron-Cohen.

But my new book Naming Adult Autism uncovers various scientific oversights which may have misguided Baron-Cohen’s research findings from the outset. And it seems flaws in a major questionnaire used to determine autistic traits could mean that many autistic adults remain undiagnosed – simply because they enjoy reading novels.

The Adult Autism Quotient test counts autistic “traits” relating to routine, communication and socialising and is used to help diagnose people with autism. It was designed by Baron-Cohen and academic Sally Wheelwright, plus three undergraduates. It launched in 2001 and continues to be reproduced across websites, books and magazines worldwide. It is also the basis of ongoing national surveys of autistic traits.

The introduction of the questionnaire aimed to create a new means to help GPs decide whether to refer patients for further autism assessment. But a second purpose seems scientifically questionable in its support of Baron-Cohen’s then new, headline-friendly theory that mathematicians and scientists typically show higher numbers of autistic traits than the general population.

The questionnaire also includes carefully-scored questions regarding maths and the arts. If your answers indicate an interest in maths, that will automatically raise your autism score. All answers suggesting an interest in fiction or art score towards “neurotypicality” – or non-autism.

This means that if you are autistic but you like reading novels, your autism quotient will be lower. So you could be less likely to be referred on to autism specialists for assessment. It also means that mathematicians may score higher on the questionnaire because they are interested in numbers –- but not necessarily because they are autistic.

Autism and literature

This “minds wired for science” idea about autistic people also creeps into literature itself – and assumptions that autistic people don’t “get” fiction are widespread in novels.

From romantic comedy – Graeme Simsion’s Rosie Project – to literary fiction – Margaret Atwood’s Maddaddam trilogy – adult autism is often reduced to caricatures. This is nearly always of a white, able-bodied male who excels at science or maths. Commendably, Simsion’s recent book The Rosie Result adopts a far more critical approach to autism. Even so, the cultural stereotype of the autistic scientist is still hard to shake off.

This fixation on autistic minds just being wired for science needs rethinking, because expectations that autistic people will succeed at either science or nothing are disabling. And this association risks streamlining future generations of autistics.

The future of autism

These stereotypes matter because they are misrepresenting what people with autism are actually like. They often present autistics to be “a certain way”, a loner or socially awkward – when in fact this varies person to person (autistic or not).

This is particularly important given that “prevention” of autism via prenatal screening may soon become available. Baron-Cohen’s commentary on autism, ethics and science states his opposition to “preventing” or “curing” autism. But alongside surveys of autistic traits and STEM talent, Cambridge’s Autism Research Centre is also leading research into autism and foetal hormones

A publication involving scientists across Europe – including some of those working at Cambridge’s Autism Research Centre – acknowledged in 2015 that prenatal tests for “autism risk” are not yet possible, but suggest their findings could be used for such research in future. This could inevitably shape some decisions about abortion.

This is why it’s vitally important that there is proper representation of autism in books, film and TV – and society as a whole that embraces the full range of autistic experience and contribution. And it starts with busting the myth that all autistic people are maths geniuses –- because for many, that couldn’t be further from the truth.