For the New Zealand Labour Party, which has been the dominant force on the left since it first took office in 1935, Saturday’s general election was a very bad day at the office.

The 24.7% of the vote Labour gained was its worst performance since 1922, and this year is the third election in a row at which the party has shed support. The heady days of Helen Clark’s final election victory in 2005, secured with 41% of the vote, must seem an eternity ago.

At a minimum, there are three things Labour needs to do before it becomes a credible government-in-waiting – and some of those changes mirror the reform challenges facing centre-left parties elsewhere, including the Australian Labor Party.

Months of uncertainty ahead

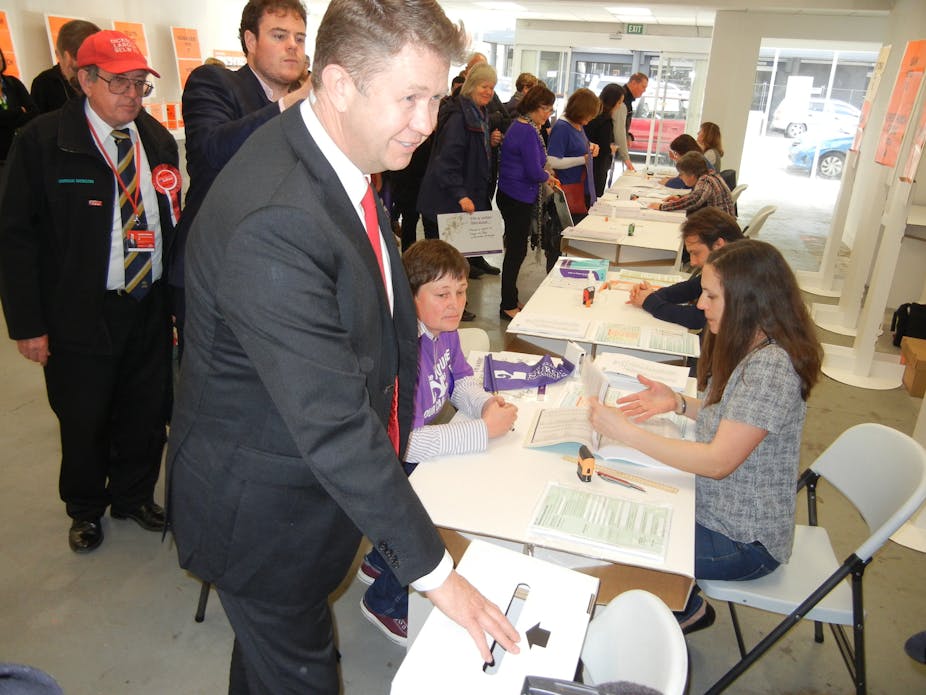

The first thing Labour needs to resolve is its leadership. Its current parliamentary party leader, David Cunliffe, has signalled his intention to remain, but some in the caucus have other ideas.

And Labour’s rules are such that matters are already getting messy. Briefly, within three months Cunliffe must seek the endorsement of the caucus. If he fails to secure the support of 60% + 1 of Labour’s MPs, an election will be triggered. That involves the wider party membership, the affiliated unions and the caucus.

Cunliffe’s support outside the caucus might carry that particular day, but if so Labour will have at the helm a leader who lacks the support of a majority of his parliamentary colleagues. It isn’t difficult to imagine how this will play out over the next three years.

What are ‘Labour values’?

The party must also be clearer about what it stands for.

Labour appears to be split between those wanting a modern social democratic party and those who believe it should launch a full-frontal assault on neo-liberalism.

That division may have contributed to the sense that the party failed to communicate its core message clearly and compellingly during this year’s campaign.

Whatever the case, Labour is not presently speaking to the concerns and aspirations of the notional “average” voter.

The shrinking red-green vote

Labour should also consider its position regarding the Greens. While red-green relations over here are not as prickly as they have become in Australia at the state and federal levels, neither are they all they might be.

Ironically, Labour’s most successful leader in modern times is partly to blame. Helen Clark had three terms during which she might have laid the foundations of a durable red-green alliance by including them in her administrations. She opted not to, and that history remains a significant obstacle to a more fruitful arrangement.

Changing this state of affairs will not be easy. As is the case in Australia, Labour has historically had to spread its policy net over a wider group of interests than have the more ideologically narrow Greens.

While Labour’s vote fell on Saturday, so did the Greens’: they won 10% of the vote, down 1.1%.

Earlier this year, Labour rejected a Greens’ proposal to campaign together as a future Labour/Greens government. On Sunday, David Cunliffe said he now regretted that decision, saying:

I think we can all learn some lessons from history. In hindsight the progressive forces of politics probably would have got a better outcome if they’d been better coordinated.

A particular sticking point is that the Greens’ position on how – or whether – to achieve economic growth does not always mesh with Labour’s.

But the parlous state Labour finds itself in and the fact that the Greens appear to have hit a ceiling suggest that negotiating a way to work more effectively together may be critical to the prospects of both parties.

Same, same, but different to Australia

The challenges facing the centre-left aside, it is tempting to see other similarities between the political landscapes of New Zealand and Australia.

For instance, recently former Australian prime minister John Howard described the evolution of a “less tribal” Australian politics in which the 40-40-20 rule of earlier eras (in which 40% of the electorate would routinely vote for the Coalition, 40% for Labor, and the balance for minor parties) has evolved into a 30-30-40 rule.

Voters have also been drifting away from the two major parties in New Zealand. But the extent of that trend can be muddied by focusing on the number of small parties in the parliament, many of which are supported by relatively small numbers of voters.

In fact, Howard’s rule applies imperfectly in Wellington. In the first three MMP elections (1996, 1999 and 2002), the combined third-party vote averaged around 35%, but in the four subsequent elections that figure has fallen to just over 23%. In short, particularly since 2005, it is the Menzies-era rule, not the Howard or Abbott-era rule, that applies in New Zealand.

That doesn’t mean that politics in New Zealand is necessarily more tribal than it is across the Tasman. For one thing, we lack a formal faction system, and there has really been only one election since 1996 at which Labour and National have run each other close: in 2005 only a couple of percentage points separated them.

In the last three elections, the gap between National and Labour has been nearly 18%: it has been National first and daylight second.

Two big blocs in NZ’s multi-party system

While New Zealand maintains the outward appearance of a multi-party system, things are not quite so clear.

True, the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system has boosted the number of parliamentary parties.

But this masks the political reality of what are fundamentally two blocs, built around the centre-right National and centre-left Labour parties.

And Saturday’s results have revealed in stark terms that one of these blocs is in far better shape than the other.

National vs Labour prospects

This is not to say that the centre-right does not face challenges. Indeed, in substantial part because of its success on Saturday, the 52nd parliament will contain no viable, long-term coalition partner for National.

ACT exists only because National regularly gifts it the seat of Epsom; United Future’s sole MP will retire at the next election; and the Māori Party serves little purpose other than to provide a fig leaf for National on Māori issues.

But that is a problem Labour would probably kill for at this point.

The National party is in rude good health. It has a parliamentary majority in its own right (something last seen in these parts 20 years ago), it is led by one of New Zealand’s most successful prime ministers in John Key, and it has a swag of new MPs champing at the bit.

Labour, on the other hand, is at serious risk of joining the Greens as a niche party. And in New Zealand, two niche parties do not a centre-left government make.