On Kawara – Silence at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City was always going to be one of the most significant exhibitions of On Kawara’s career.

After all, it is the first fully representative survey of five decades of the artist’s practice, which focuses on exploring time and our different perceptions of its scale. The Japanese-born artist, based in New York City since 1965, worked closely with the Guggenheim on this exhibition and his presence is clear throughout its narrative.

However, the death of Kawara in July last year, only seven months before the exhibition opened, now changes the context of that story: On Kawara – Silence is no longer an exploration of an artist’s ongoing practice, but an elegy that maps an artist forever absent and a life now complete.

Kawara is perhaps best known for his series of Date Paintings, which form the longitudinal body of work titled Today. Each canvas in this extensive series carries nothing but a line of white text on a dark coloured background conveying the date it was created.

The Date Paintings begin on January 4, 1966, the year after Kawara moved from Japan to New York. In the book that accompanies the exhibition, Maria Gough notes that, “There are no published photographs of On Kawara after 1965”. It is as though this date marks the rebirth of Kawara as a data-generating entity, which ceaselessly maps and traces itself through space and time.

Daniel Buren says in his essay for the book:

On Kawara was not born on such and such day and such and such year like everyone else. Rather, as he would have it, he indicates on August 31, 2002, he was aged 25,453 days.

We rarely count time in thousands of days, instead using smaller numbers of years, which we conceive as a cycle rather than a succession of days. It’s an uncommon approach to time that disrupts how we usually conceive and contain time.

The Date Paintings form the backbone of On Kawara – Silence, beginning with the January 4, 1966 canvas, and continuing up the Guggenheim’s spiralled ramp. The Guggenheim is a notoriously difficult exhibition space. Unlike most “white cube” style galleries, which guide the audience from room to room, the Guggenheim has a continuously sloping ramp that corkscrews from the ground to the top of the building.

Many Guggenheim shows are organised from the top down (take the elevator up and walk down), but On Kawara – Silence climbs up the spiral, with its side rooms creating intervals that group together works into sections, such as Kawara’s Paris-New York Drawings, his Codes works, which use private ciphers to create coded messages and his Journals, a detailed inventory of his Today series since 1965.

As the audience climbs the ramp, they pass three months of Date Paintings from 1970 (January 1 to March 31). In reproductions, Kawara’s Date Paintings often seem sterile, aesthetically dry and – let’s be frank – dull. This is the curse of much conceptual art work, where the focus is the idea, not the art object or the way it looks. But in the flesh, these works are unexpectedly beautiful in their execution.

As Jeffrey Weiss notes in the catalogue, “the paintings are slowly crafted in multiple layers”. The hand-painted lines that render the text are delicate and accurate; the canvases are flawlessly constructed. Although, as Weiss says, “these cannot be identified as conventional objects of aesthetic contemplation”, there is a conceptual aesthetic at play – there is a beauty to the complexity and sheer obsessive scale of his mapping.

Each canvas is accompanied by its storage box, in a display cabinet in front of the paintings. Each box is lined with a section of a daily newspaper from wherever Kawara happened to be at on that day.

The box for January 4, 1970 is lined with a New York Times picture of the groovy Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon, with children, in their 1960s convertible. The box for January 9, 1970 is lined with another Times story, about the Apollo lunar mission conference. January 15 is lined with the Times’ death notices.

With these snippets of newspapers, the seemingly sterile Date Paintings open onto a whole world of the times and places into which they were created. The dates are given a human scale and a social dimension. This is expanded further in Kawara’s I Read works, further up the ramp, in which the artist shows us everything he read during the years 1968-1979.

Kawara’s Self Observation works, I Got Up, I Went and I Met, likewise map the temporal, location and social dimensions of Kawara’s days. I Met is a day-by-day typewritten catalogue, arranged in bound volumes, recording everyone Kawara met on any given date. On some days he met 20 people, on others only one.

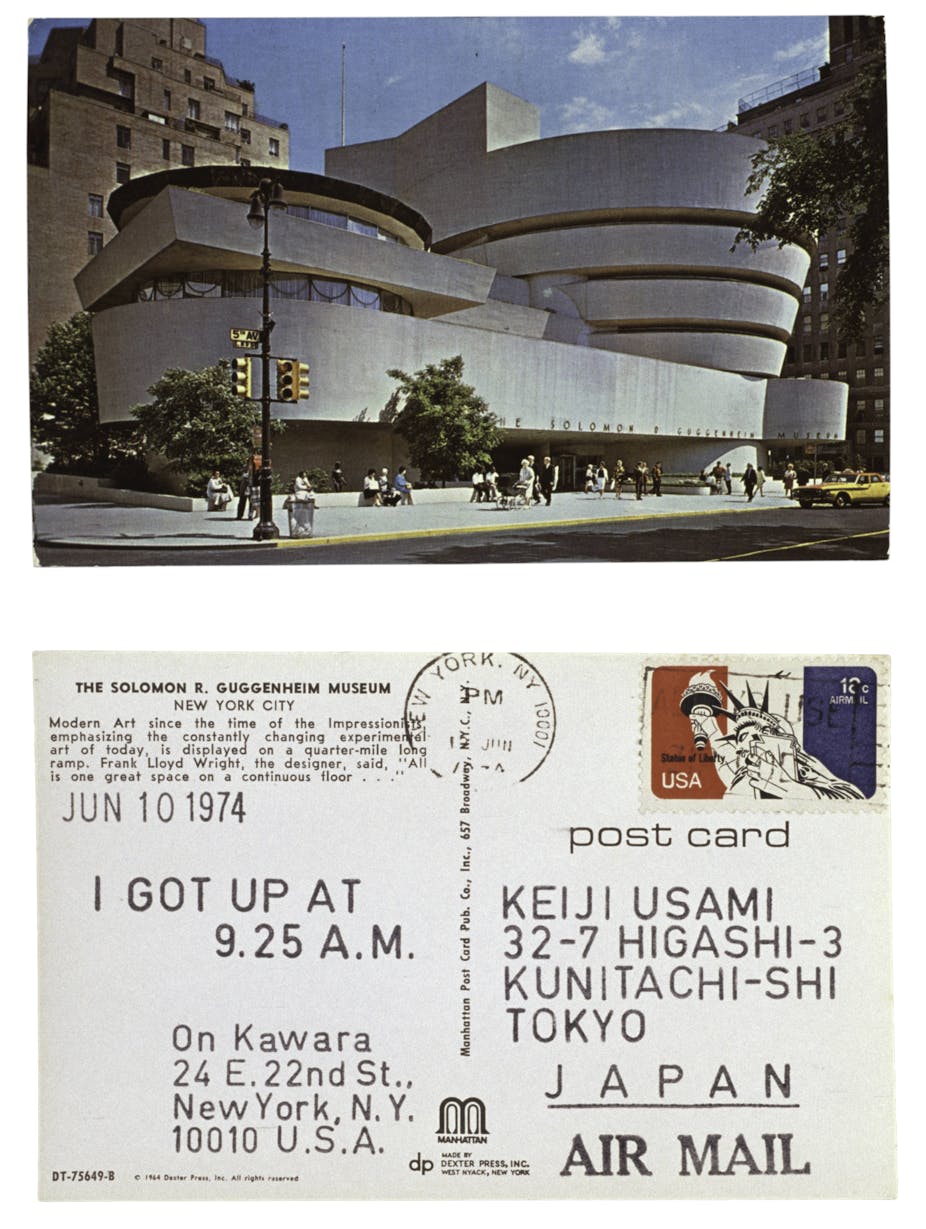

I Got Up consists of 11 years of daily postcards, beginning in 1968, sent to friends and associates. The addressed side of the cards read in rubber-stamped text “I got up” followed by a time, which is usually around 10:00-11:00am. Displayed in large double-sided frames, from one side we see only the text with the varying times of Kawara’s rising; from the other side the postcards read as a mass of cheaply printed picture postcards of New York, Mexico City and other places where Kawara visited.

Similarly mapping Kawara’s geographical coordinates, his I Went work traces in red line on a map everywhere Kawara went in the location he was in at the time. One of the pages on display mapped Kawara’s movements around his hometown in Japan, Kariya – the date is the day after my own birth. At this point, the relational social dimensions of Kawara’s work became clear.

Our own times overlap with Kawara’s, and we inevitably map our own days and locations to those of Kawara. These may just be calendar dates, but each one has billions of possible permutations, and we too are among them.

In 1969, Kawara began sending telegrams declaring “I am not going to commit suicide don’t worry”. These mutated into the more positive message of “I am still alive” on January 20 1970 and continued in telegrams to friends, art collectors, curators and other artists, such as Sol Lewitt, irregularly until 2000.

The gesture echoes that of Marcel Duchamp, who in August 1913 took a vacation in a seaside town on the estuary of the Thames, and wrote a postcard to fellow artist, Max Bergmann saying, “I am not dead; I am in Herne Bay”. In both cases, the artists’ affirmation of being alive is inevitably overshadowed by the inevitability of their death.

The restating of “I am still alive” cannot help but be a memento mori, a reminder of death.

On July 15 2014, The New York Times reported the death of On Kawara, stating that his family “declined to provide the date of death or the names of survivors”. Perhaps this is ironic, given the amount of detailed information that Kawara gave us about his life since the mid-1960s.

But then, maybe it’s not. Kawara’s work tells us so much of the metadata of Kawara’s life, but nothing of Kawara. We might know he was in New York on 1 April 1969 and got up at 8:15am, but most of us still don’t even know what the artist looked like.

In some ways, Kawara’s extraordinary 1960s conceptualist project, of documenting every detail of one’s life regardless of its banality, has drifted over the years towards the norm. In particular, Kawara’s work seems to presage a world of social media, in which we’re compelled to tweet, check-in, update and photograph our meals, to leave a trace of the most banal daily metadata of our existence. Kawara’s obsessive self observation has become automated and the norm.

The book for On Kawara – Silence gives a clear sense of the exhibition having been severely disrupted by Kawara’s death during its final planning stages. Daniel Buren’s essay ends with him saying that he has just learned about Kawara’s death:

He can neither say that he is dead, nor can he say that he is no longer alive. The interruption here is all the more brutal.

Jeffrey Weiss likewise says that the exhibition “now inevitably serves to mark his loss”

Yet, On Kawara – Silence, spiralling towards the inevitable apex of the Guggenheim’s ramp, feels less like a life interrupted than a life now complete. Perhaps it reminds us in an unexpectedly poetic way that with life and death, interruption and completion are the same thing.

On Kawara – Silence is on display at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City until May 3.