The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is proposing to regulate some medical mobile applications, or apps, in an apparent bid to protect consumers from harming themselves or others.

At first sight, this may appear as over-the-top meddling. But in fact, the proposal doesn’t go far enough to warrant that charge.

Oversight of medical apps

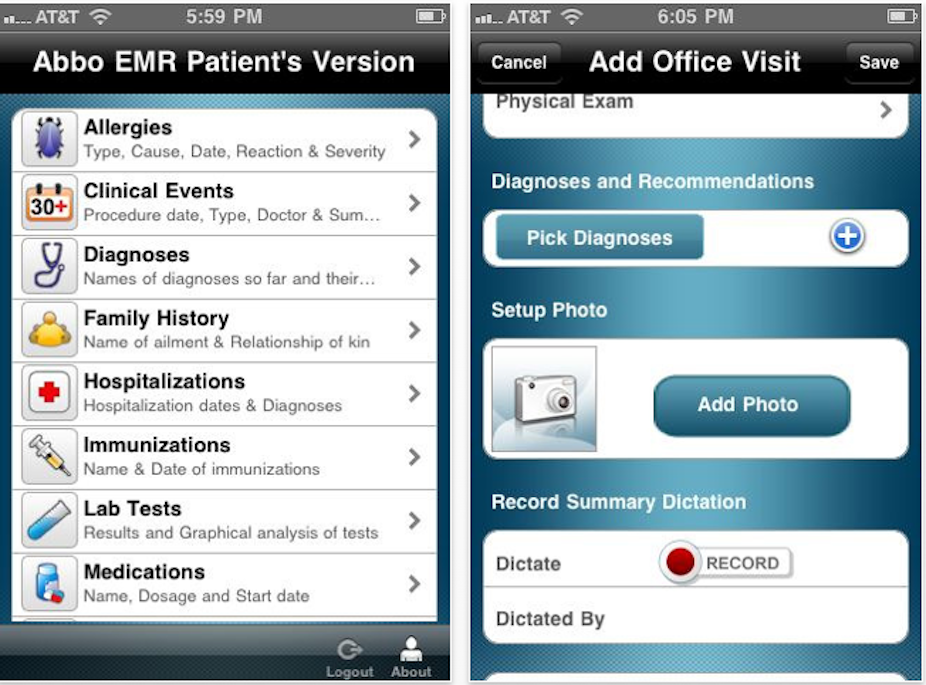

Medical apps have grown in popularity, covering anything from monitoring fertility to making diagnoses based on clinical data.

The FDA would like oversight on two specific kinds of medical mobile apps:

those where the device that runs the app is used to present data from a separate and active device (for example, it displays the results of an X-ray scan): the app “transforms a mobile platform into a regulated medical device”; and

those where the device is attached to passive sensors (such as a blood pressure sensor) and the app interprets and processes information: the app becomes “an accessory to a regulated medical device.”

In both of these cases, the active or passive instruments that are to be connected to the device and linked to the app have already undergone FDA scrutiny.

The proposal is therefore relatively benign and a logical extension of what’s already in place. Implementation would also only affect a small percentage of apps available on popular apps markets.

This may well be a calculated move by the FDA. Were its proposals to go further – requiring oversight of all medical apps – they would likely cause an uproar.

And where to draw the line to separate health apps from lifestyle apps? There are many examples of these and some are quite popular.

Consider, for example, apps that allow couples to track fertility (above), or keep track of medication intake, or even analyse sleeping patterns.

The FDA’s move raises questions about the necessity as well as desirability of similar future government moves, not just in the health sector.

After all, some well-intended apps may cause accidents or pose public safety concerns when used irresponsibly. These are of far more concern than has ever been the case with desktop software.

For example, it would be easy to create an app for sharing data about planking success and for users to rate the most successful or outrageous planks.

But one only has to think of the recent death attributed to the planking craze to see how this harmless idea can have a negative social impact.

However, for practical as well as philosophical reasons, it seems unlikely any government will attempt to actively regulate all apps on the market.

Implications for Australia

Most medical apps are sources of information so they fall outside the regulatory scope of the Therapeutic Goods Administration(TGA).

Those that make diagnoses based on clinical data could be investigated by the TGA if they received a complaint about the app. That’s because such apps may be classified as therapeutic goods.

As in the United States, apps considered medical device software would have to be submitted for approval just as other medical software.

A TGA spokesperson said the regulatory body would monitor advances in medical device technology, the Australian Doctor reported yesterday.

Alternatives to regulation

Thankfully, there are several alternatives to full government oversight.

First, governments could let the market (for instance through popularity ratings) along with the legal system separate the good from the bad.

This is roughly the current situtation and it works well enough at present. Unfortunately, this approach usually deals with tragedies after they happen.

Alternatively, the device manufacturer could control what apps become available. This is Apple’s business model and appears to handle public health and safety concerns quite well.

For instance, it’s conceivable for Apple to be sued if an app they approved could be shown to have caused real harm. This provides incentive for the company to apply a rigorous screening process for apps before releasing them into the market.

Finally, governments could create special categories in app markets and special interest groups and relevant government bodies could certify good apps.

In this instance, a developer would still be able to publish their app on the general market, but users would become more willing to put their trust in the app once it receives an official stamp of approval.