George Osborne made a great deal in his recent budget speech of the “northern powerhouse”, claiming that the north had grown faster than the south over the last year and pointing to the success of the coalition government in ensuring investment and job creation was not concentrated in southern cities.

Obviously this was a highly political statement. The north has traditionally been anything but a stronghold for the Conservative Party – which clearly believes it can take ground from the Labour Party in May. Quoting 2013 figures (misleadingly as it happens) the chancellor claimed that more jobs had been created in Yorkshire than in France and announced various initiatives aimed at winning the hearts (and votes) of a region which has tended to represent stony ground for the Tory message in the past.

But viewing the economic situation in Britain as a north-south divide tends to oversimplify things – and calls for a closer look. There are large variations in economic performance across the cities and regions of the UK. To be fair, there is a broad north-south pattern to these disparities – but there is also substantial variation within those broad areas. Some northern cities (such as Manchester) are doing relatively well and some southern cities (such as Hastings) are doing relatively badly.

But despite many initiatives by the current and previous governments, these disparities remain large and persistent. On some measures, they have widened since the global financial crisis.

Voting with their feet

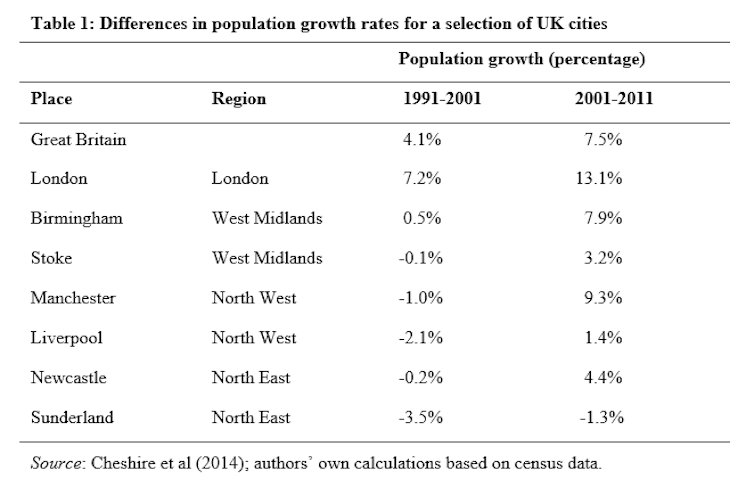

Research shows how these differences play out in terms of population growth for a selection of UK cities. The table below highlights three important trends: first, the continued strength of London; second, the recent improvement in performance of some cities; and third, the variation in performance, which is apparent even for neighbouring cities.

These patterns are confirmed by Cities Outlook – the most useful source of detailed data on the economic performance of UK cities. The latest report shows that between 2004 and 2013, population growth in cities in the south was twice the rate of cities elsewhere.

The growth in businesses was similarly unbalanced with a 25% plus increase in cities in the south compared with an increase of nearly 14% elsewhere. The figures for jobs are even more dramatic: cities in the south had over 12% more jobs in 2013 than in 2004, while cities elsewhere saw only around a 1% increase. The differences are even more marked for private sector employment (because public-sector employment is more evenly distributed).

London versus the rest

As the figures make clear, a big part of the story concerns the geographical concentration of economic activity in London (and the south-east).

In explaining this success, neither finance nor the globally oriented part of the London economy are as important as suggested by popular discussion. Financial services are clearly important, but most of London’s long-term job growth has come outside finance or those sectors closely linked to it.

London is a preferred location for the super-rich, but this is a tiny, if much publicised, minority. In terms of overall transactions, recent increases in foreign demand are swamped by increases in demand from first time buyers and other sources of domestic demand, which is the main driver of the London housing market.

In fact, what is most distinctive about London’s economy is its competitive strength and skill levels across a wide range of services. The capital has a high concentration of skilled workers who would be paid relatively well wherever they lived. In turn, that concentration is partly because London provides greater opportunities for such individuals to use and develop their talents.

All of this means that London has higher wages, more expensive housing and a greater general cost of living – and the gap in all of these has risen as wage inequality has grown since the late 1970s. But at least for those who are young, able and willing to economise on housing costs, London offers opportunities that are simply not available elsewhere. And since many later move on to other areas of the country, London also acts as a source of highly skilled workers for local economies throughout the UK.

Whether this seems good or bad for the UK partly depends on how we tell the story about what is going on. If, as is popular, we talk about London sucking the talent from the rest of the UK, then this sounds like a pretty bad thing. But if we think of London’s performance as the result of a large number of people responding to the opportunities that London offers, then this changes the debate.

Size matters

Rather than focus on London’s dominance, we could ask why other large UK cities do not offer similar economic opportunities and what can be done about it? The evidence suggests that what we need is, paradoxically, the growth of one or two other large cities so that they provide similar opportunities. This is because overall population size helps generate more opportunities (as a result of what economists call “agglomeration economies”). So too does the concentration of skilled workers and of certain types of knowledge-intensive industries (which employ those high-skilled workers).

If size matters, perhaps the issue is not that London is too big, but that some of our second cities are too small. International comparisons are suggestive. Zipf’s Law (which says that the second-largest city tends to be half the size of the largest, the third city a third the size of the largest, and so on) suggests that the UK’s cities after London all look too small.

Part of the reason for this is that population is quite spread out across a number of cities. Concentrating population in a smaller number of larger cities would bring us more in line with other countries. A powerful body of research points to the importance of agglomeration economies and the barriers to realising the benefits from those economies. The UK planning system is particularly at fault here. In short, these international comparisons do raise questions about the relative size of our cities.

Local growth policies

In principle, the coalition government’s changes to the institutions and structures that deliver local growth policy allow for greater policy variation across areas. The move from ten regional development agencies to 39 “local enterprise partnerships” in most cases moved strategic decision-making on economic development policies – particularly on transport – to a more appropriate scale: somewhere between local authorities (usually too small) and regions (too big).

The deal-making approach also allowed for greater policy variation. In theory this gave cities power to negotiate deals with the government, giving them greater say over spending in their wards.

In practice, however, decisions on deals are still ultimately made by central government. And this, combined with the centralised dispersion of funds from the Regional Growth Fund continues to constrain local decision-makers. The coalition government seems willing to go further – at least in areas with a good track record and credible governance arrangements.

For example, recent announcements of “Devo Manc” involve considerable devolution to Manchester. But this “earned autonomy” model is criticised by those who would like to see more systematic devolution to all local areas.

Policy variation across areas

While in principle, the coalition government’s reforms allow for greater policy variation across areas, the extent to which politicians in Westminster can live with the consequences of varying economic performance remains to be seen. The Chancellor’s “Northern powerhouse” agenda – which aims to create a counterbalance to London by better integrating and empowering the collection of Northern cities – highlights these tensions.

The evidence suggests that agglomeration economies work at smaller scales than the entire Northern economy, so more uneven development across Northern cities may be necessary if we want one of these cities to provide the kind of opportunities available in London.

Labour, with its focus on inequality, finds these issues even harder to address and have a tendency to focus on the objective of improving growth across all failing areas – regardless of whether this is achievable or the best way to help individuals.

Greater concentration, combined with local variation and experimentation is a significant challenge. As we assess how the parties respond, it is helpful to remember that we ultimately care about the effect of policies on people more than on places.

The various proposals for rebalancing the economy should be judged on the extent to which they improve opportunities for all, rather than whether they narrow the gap between particular places.