We shouldn’t need a Super Bowl commercial costing around $10 million to remind us that information is supposed to matter in a democracy.

Yet the Washington Post thought we did, so it told 111 million Americans watching the Super Bowl that “knowing empowers us, knowing helps us decide, knowing keeps us free.” It was another sign that our longstanding faith in the power of information is faltering, undermining democracy. And unless we want this faith to be replaced by authoritarianism, we need to reform our education and political systems to restore our faith in facts.

I became interested in studying the history of that faith in Canada and the United States because of my experiences as an investigative journalist, a profession premised on the importance of knowing.

During the 10 years I covered provincial politics in British Columbia, Canada’s westernmost province, I saw how the information I obtained could force bureaucrats and politicians from office or make much needed reforms. But it was an absence of information during the World Wars that helped elevate its already exalted place in our society.

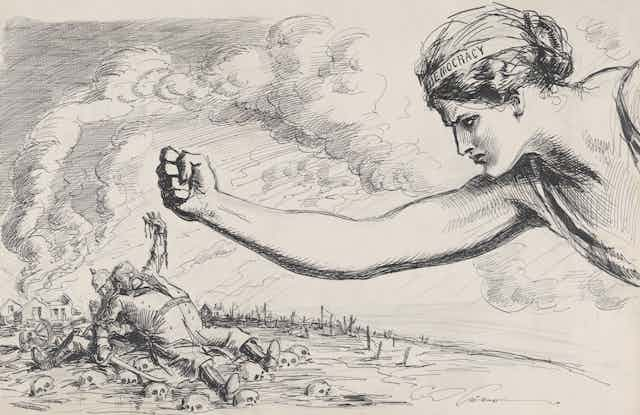

Amid the ruins of those conflicts, we struggled to understand what had caused millions to die by human hands not once but twice in the span of 31 years. For some observers at the time, the answer to that question was government propaganda, censorship and secrecy.

Posters were blamed for turning neighbours into enemies. Broadcasts were blamed for turning peace-lovers into war-mongers. And bureaucrats were blamed for purging anything but propaganda from the public square.

Knowledge is power?

As a result, many analysts felt that knowing might have averted those wars and their atrocities.

For example, the reasoning went, if the Germans had only known the truth about their leaders and supposed enemies, they would have never backed the Nazis’ expansionistic and genocidal policies.

In other words, to paraphrase the Washington Post, knowing would have empowered Germans, helped them to decide and kept them free from the chains of authoritarianism. The availability of information came to be seen as a guarantor of future peace, as well as a means of distinguishing the United States and its Western allies from fascist and later communist countries.

Indeed, such faith in information is central to our assumptions about how a free and democratic society should function. With that information, we are supposed to be able to elect better representatives, purchase better products or make better investments.

In doing so, we can control our governments and corporations. And that information can make us feel more certain about them, creating the trust we need to have confidence in these institutions.

Such beliefs profoundly influenced postwar politics. It was a period where information was seen as the curative for many of society’s ills — a dynamic I’ve detailed in a chapter soon to be published in the edited volume Freedom of Information and Social Science Research Design.

This was the era of Cold War big governments and big businesses, where bureaucrats and company men seemed to know more about us than we did about them thanks to their secrecy, surveillance and seemingly limitless data banks.

This was also the era where governments and businesses exposed citizens and consumers to all manner of perils — from asbestos, thalidomide and radioactivity to DDT, unsafe food and accident-prone automobiles. And this was the era in which public relations and advertising seemed to threaten our ability to make decisions about these institutions, whose behaviour seemed to have become more uncertain and uncontrollable.

Faith misplaced

These concerns led to what the sociologist Michael Schudson has referred to as the rise of the “right to know” — demands by environmental activists, consumer advocates, investigative journalists and others for measures that could force the release of information, from freedom-of-information laws to product-labelling rules.

Unfortunately, in the years since then, our faith that the resulting information would bring us control and certainty over governments and corporations has proven to be misplaced.

And that’s because not enough of us are making the kinds of decisions our political and economic systems assume we will. Whether it’s in the shopping aisle of a grocery store or on the floor of a legislature, we are making too many uninformed, irrational and unempathetic decisions.

You can see it when we elect or appoint candidates with histories of misconduct and incompetence. You can see it when we vote for parties or policies that work against our long-term or even short-term interests. And you can see it when we fail to act on everything from economic and social inequality to climate change.

There are many potential explanations for our seeming inability to make informed, rational and empathetic decisions — from partisanship and competitiveness to laziness and prejudice.

But regardless of which explanation we believe, the result is we find ourselves living in an age of information impotence. Our faith in its power is faltering, making the world even more uncertain and uncontrollable than it was in the 1970s.

It’s against this backdrop that many of us are desperately searching for other means of certainty and control. In doing so, some are spurning democracy and being seduced by the pseudo-certainty and control of fake news and political strongmen.

‘Truth is hard’

That’s why the Washington Post preached the gospel of information to football fans. It’s why the New York Times ran similar advertisements telling viewers about how the truth is “hard” but “more important now than ever.” And it’s why the March for Science’s pleas for “evidence-based policies” can perhaps more clearly be heard as prayers for information to matter again.

So what does this mean for anyone who cares about democracy? In part, it means we need to be doing more to teach our children how to evaluate information, as well as make informed, reasoned, empathetic decisions in both their private and public lives.

In other words, we need to be giving them the skills needed to be responsible consumers and citizens, as well as political and economic leaders.

But we also need to be doing more to make sure their decisions matter within the context of our private and public institutions. Right now, those institutions can seem impervious to public opinion and decision, whether it’s because of gerrymandering, campaign contributions or party discipline. And that means making substantial reforms to how governments and corporations have traditionally functioned.

We have little time to make these changes and restore our faith in the power of information. The problems of the present are becoming bigger by the day. And if we don’t make changes, we won’t have much of a future to look forward to.