This article was published with the Réseau français des instituts des études avancées (RFIEA) in issue 31 of the bimonthly journal Fellows under the title “Mégalopoles, villes-musées, bidonvilles : la ville au XXIᵉ siècle”.

The French daily Le Monde recently ran an article with the headline “The 570 slums that France doesn’t want you to see”, drawing attention to the hundreds of informal settlements in France (113 in the Paris region alone) where 16,000 inhabitants live a marginal and precarious life.

In France, evictions are legally prohibited during the winter, from November to March. One of the unintended consequences of the law is that there is often a rush to remove squatter settlements just before the suspension comes into play, unleashing an even greater level of exclusion.

While the Le Monde article is instructive and can be deeply troubling for their readers, who as a majority would not associate anything so bleak with French urban reality, it also unwittingly plays into the narrative of the French state, which, as the French political scientist Thomas Aguilera observes, has consistently invoked race and migration to defamiliarise the poverty question. While the article interchangeably refers to slums and “illicit camps”, the former has been carefully avoided by the French authorities, who instead use “camps” or “squats” to disengage the slum as a political object.

The point here is not so much about our continued preoccupation with the term “slum”, a pejorative and debatable term that obliterates a wide range of settlements and meanings across the globe. Instead, it’s the fact that a major French media considers the emerging issue of poverty in France significant enough to merit a deeper analysis – that it’s not just a temporary manifestation but a broader structural change.

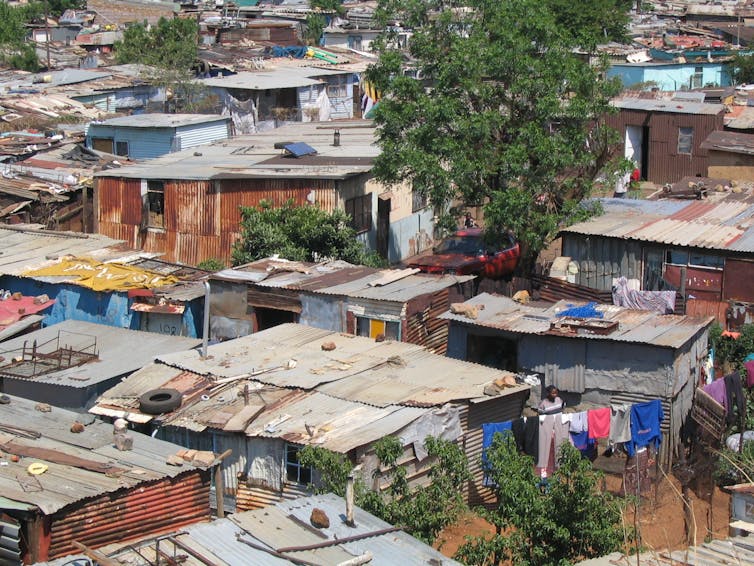

Even though academic debates are nuanced as to the extent to which slums can be seen as a constitutive dimension of urbanization, it cannot be denied that they – in whatever variegated forms they might appear – are an increasingly shared phenomenon across the global North and global South.

The squat gone global

What is being experienced as dispossession and displacement in the global North could well be closer to the American sociologist Saskia Sassen’s new logics of expulsions – it’s happening at the edges of the system and may not be anywhere near the scale of what is seen in cities of the global South. However, the chronic vulnerability associated with urban poverty on both sides of the binary divide requires some honest examination. Thus, Alex Vasudevan, a geographer based at Oxford University, finds that there is an emerging geography of squats around the world. While the distribution is uneven, understanding the phenomenon requires being aware of the political-theoretical constructs in the North and the South.

In this context, we need a relational rather than an absolute approach to our study of such settlements, of which slums are just one part, and whose frames of reference stretch across the global North and global South. Identifying points of overlap can provide a renewed reconceptualization of these precarious urban worlds. Such efforts must be able to not only accommodate the wide variety of informal settlements but also generate a deeper cross-referenced historiography, outlining the contemporary characterisations of this phenomenon.

As asserted by urban studies scholar Jane Jacobs, the kind of co-production of knowledge that we anticipate needs to be able to place side-by-side radically different and even incompatible urban geographies. Thus, while looking at the genealogy of informal settlements in European cities might be a useful project, what would be more radical is to bring them face to face with the phenomenon of squats in, say, North Africa and the Middle East, establishing connections across these putatively separate worlds and providing a global measure of poverty and inequality.

We see here an opportunity to resist producing another prosaic study of slums, and instead rethink some of the common biases against them, including the fact that while a considerable number of urban poor live in the slums, not all slum dwellers are poor, and more importantly, a significant proportion of the urban poor do not reside in the slums.

Global cities or megacities ?

Despite the postcolonial turn in urban studies, there is still a persistent developmentalist binary entrenched in a project of modernity, unfavourably contrasting the “megacities” of the global South – implicitly underdeveloped – with the superlative normativity of the “global city” in the North.

More recently, the emergence of a discourse emphasising the dispersed nature of global urbanism in both the North and South renders “megacities” and “global cities” strangely familiar to each other. What they share is a sense of planetary transformations, without the trappings of modernization if not globalization.

We can easily argue that Mumbai is a “global city” of the South and not just a city in the global South, including it in the roster of cities such as Istanbul, Mexico City and Sao Paolo, undermining the conventional list of European and American cities. This offers a better understanding of the scope of possibilities and invites us to embrace new challenges, in parallel with the dominant global urbanism agenda developed by international policymakers. However, these two ways of approaching the urban problem are yet to confront each other comfortably and risk contradicting each other.

In October 2016, UN-HABITAT launched its ambitious New Urban Agenda at the Habitat III conference amid much promise of a post-development era where, as South African academic Susan Parnell has discussed, there is a real possibility of overcoming the very different epistemologies of urban and development studies) which has resulted so far in a restricted understanding of slums and poverty.

By seeking to reconcile these two epistemologies, urban issues could emerge by and for themselves instead of being conceived as development objectives limited by sectoral boundaries. While initial reactions to these aspirations and endorsements have been cautious, if we aspire toward a productive outcome from this effort, especially in terms of rethinking important urban challenges such as slums and megacities, there needs to be a clear resonance between global urbanism within urban studies and a policy-level global urban agenda (led by UN, World Bank and other international organizations), without compromising the heterodoxy of these emergent arguments. This task might seem like a tall order but nevertheless needs to be undertaken.

The network of the four institutes of RFIEA has welcomed more than 500 researchers from around the world since 2007. Discover their work on the site Fellows.