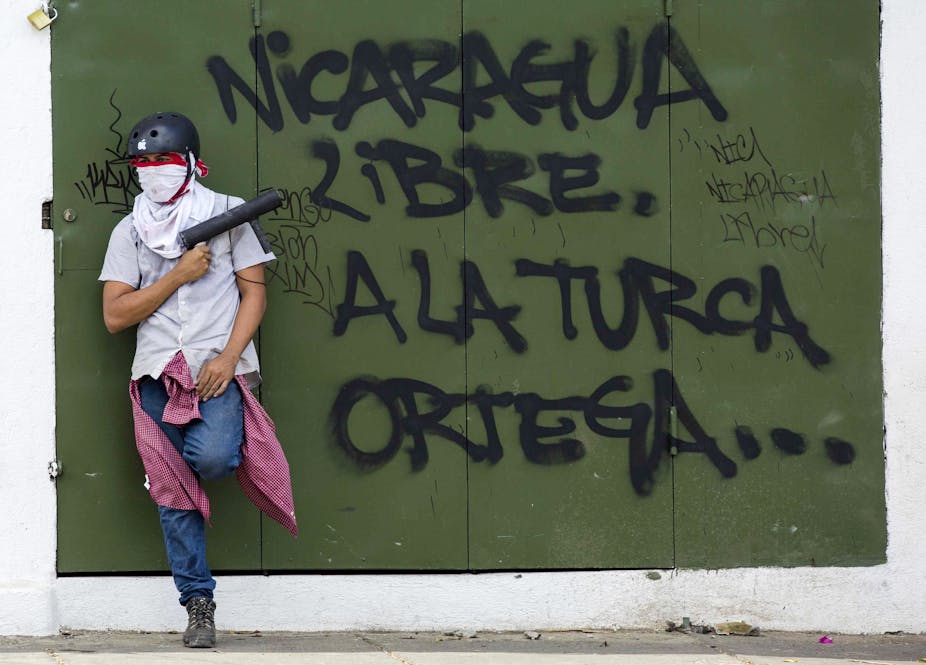

In recent days, protests against social security reform have prompted a violent crackdown in Nicaragua. At least 42 people have been killed but the final figure will likely be much higher; the government has refused to release the bodies of some of the dead until families sign a disclaimer which states that the police were not responsible. This is a level of state violence Nicaragua hasn’t seen since the Somoza dictatorship was overthrown in 1979.

The crisis was sparked by proposed changes to the Nicaraguan Institute of Social Security (INSS), requested by the International Monetary Fund, which would entail a rise in social security contributions and a reduction in pensions. This was a guaranteed political flashpoint; government officials have been accused of siphoning off INSS funds for years, and a previous protest at INSS changes in 2013 had triggered what was until this week one of the government’s harshest responses to peaceful protest.

The INSS reforms were announced on April 18, when students were already in the streets protesting the government’s mismanagement of an ecological crisis, and this contributed to the size of the protests. But it’s the violence of the government crackdown, rather than the reforms themselves, that has transformed the balance of political power. And the underlying tensions fuelling that violence have been building for more than a decade.

Holding the reins

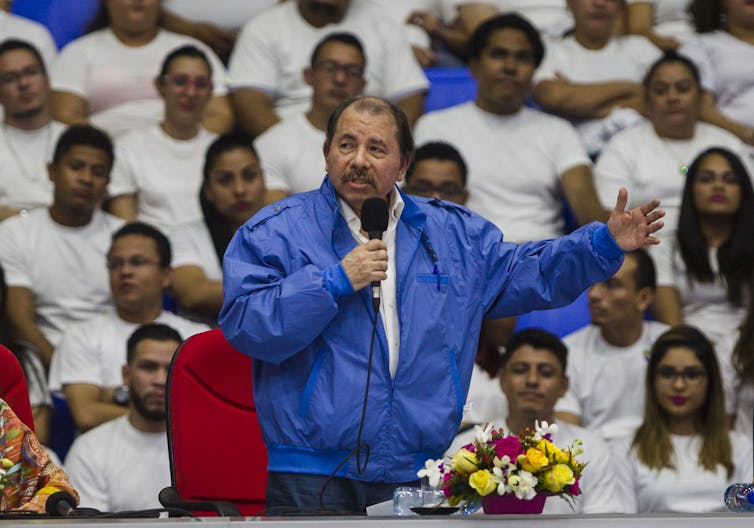

Nicaragua’s president, Daniel Ortega, first came to power in July 1979 as one of the leaders of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), which spearheaded a broad-based popular movement that toppled the Somoza dictatorship. Ortega was initially co-ordinator of the country’s governing junta, and was then elected president in country’s first ever democratic elections in November 1984. A US-backed guerrilla war and economic embargo took a considerable toll, and in 1990 Nicaraguans voted the Sandinistas out of office.

Ortega was elected president once again in November 2006, after 16 years of right-wing anti-Sandinista government. The Nicaraguan constitution limits presidents to two terms, but Ortega had the limit removed and was re-elected in 2011 and 2016. He has now held office continuously for more than a decade.

Ortega’s so-called “second revolution” has differed substantially from the first. In an effort to broaden his appeal, Ortega has built alliances with groups that opposed the Sandinistas in the 1980s.

He has courted the Catholic Church, supporting a total ban on abortion even where the mother’s life is at risk. He has also formed an alliance with COSEP, an association of business leaders who, until the present crisis, had tacitly supported him provided he consulted them on economic matters.

Alongside these innovations, Ortega has continued to rely on his traditional bases of support. Since the 1990s, Nicaragua’s army and police force have been ostensibly apolitical, but both were built from scratch during the revolutionary decade, and to this day they retain strong historical links with Ortega’s FSLN. A series of anti-poverty programmes, partially funded by Venezuela, won support from poor communities, and many poor Nicaraguans have continued to consider Ortega the standard bearer for Nicaragua’s revolutionary tradition.

The result was what looked like a convincing hold on power. In 2016, Vanderbilt University’s LAPOP survey found that 44% of Nicaraguans intended to vote for Ortega in that year’s elections, far more than pledged support for any other political party. Yet by closing off all space for political dissent, Ortega and the FSLN government have squandered their advantage.

Going too far

Since 2008, election observers have reported irregularities in every local and national election. The most recent election was a foregone conclusion because the leader of the main opposition party was removed from office by Nicaragua’s Supreme Court less than five months before the vote.

The violence has prompted open opposition from the institutions that Ortega relies on. Senior members of the Catholic Church came out in support of the students, and Managua’s cathedral was used as a centre to provide food to protesters during the worst of the violence. Two former chiefs of the army (including the president’s own brother) have expressed concern, while the FSLN’s former allies in the private sector participated in a massive demonstration in Managua on April 23.

The history of the 1979 revolution still shapes political discourse in Nicaragua, so parallels with the violence of the Somoza era have provoked particular revulsion. The symbolism is potent: scores of demonstrators were held and allegedly beaten at El Chipote, the prison where Ortega himself was held and tortured by the Somoza regime between 1967 and 1974.

Ortega may be saved by the fact that there is no viable candidate to replace him. He and his family have dominated the FSLN for many years, and no opposition party can as yet claim a substantial electoral base. But as the government continues its crackdown on dissent – hospital workers and other government employees were reportedly fired for participating in the April 23 protests – opposition continues to build.

Human rights organisations have demanded an independent truth commission to investigate the violence of the past week. And given the outrage felt by most Nicaraguans right now, it’s difficult to see how Ortega can stay in power without acceding.