A specter continues to haunt the Arab world – the specter of regionalism.

The idea that illogical national boundaries, drawn by colonial overlords divided what should have been a pan-Arab region has been a recurring theme in the Arab world. It seemed to have been consigned to nostalgia. But now it is back.

20th century resentments

The 20th century in the Middle East was marked by a shift towards nation-states. The peculiar way that British and French officials divvied up much of the post-Ottoman Middle East into new colonial territories during the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement proved particularly irksome to many people in the region. It left in place a sense that borders made little sense and were permeable.

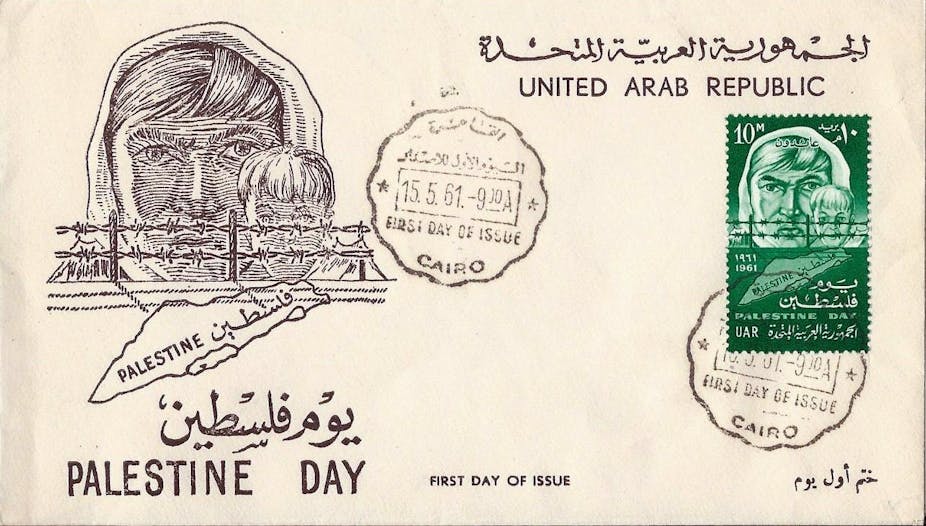

This was tapped into by Egypt’s charismatic president Gamal Abdel Nasser, among others, in the 1950s. During this period, parts of the Arab world agreed to political union with, for example, the United Arab Republic integrating Egypt and Syria. This period ended with the Arab regional crisis set off by Nasser’s spectacular failure to dislodge Israel in the 1967 Six Day War, which caused, in the late scholar Fouad Ajami’s famous phrase, “the death of pan-Arabism”.

Audio-visual Arabism

However, if an explicitly political Arab regional identity took a hit after 1967, the idea that Arab societies are linked with each other in ways that are distinct from other regions in the world remained in place. This helps to explain, for example, Arab solidarity with Palestine and the rapid rise to success of the Al Jazeera satellite news network. The emergence of Al Jazeera, in particular, helped catalyze a strong Arab regional narrative in the decade preceding the Arab uprisings in 2011.

Al-Jazeera may have gained notoriety in the US in the 2000s because of some American commentators’ perception of an anti-Western bias in their news coverage. Yet its true significance was in helping to ignite the always-smoldering embers of Arab regionalism. Tunisians, Egyptians, Yemenis, Libyans, and Syrians, among others, began to see themselves as linked in a generational struggle to take large risks to seek more populist, accountable government.

Region in turmoil

But if we fast-forward from 2011 to today, the Middle East is in disarray.

Egypt is back to a military ruler after a fitful experiment in greater democratic accountability. The anarchy of Libya’s and Yemen’s political situations is of increasing global concern. Syria’s civil war is far from over, and has included the rise of the Islamic State. If its recent elections make Tunisia look like the Arab world’s best hope for a transition to a stable democracy, it does not suggest anything resembling a regional pattern at all.

Indeed, divergent political trajectories are present even beyond the group of states most affected by the 2011 uprisings.

Iraq’s decay is the second part of the Islamic State story. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have now moved beyond their intense but civil rivalry to a more heated and open conflict around support for political Islamists. And, for all the pro-Palestinian street protests, Israel’s recent war with Hamas in Gaza did not catalyze Arab government solidarity in obvious support of Palestine.

Enduring regionalism

The key to the endurance of pan-Arabism is not outward political similarity among Arab countries. Instead, regionalism matters because of the continued popularity of the alternative model it offers to nation-states in the popular imagination.

Iraq’s very possible breakdown into smaller units despite its existence as a modern state since 1920 on the one hand and, on the other, the geographical ambitions of the Islamic State are related signs of the relatively unsettled nature of territorial nationalism.

Seen in a different light, the ambitions and antagonisms that put Arab governments at odds with supporters of non-national concepts for political organization are part of an ongoing struggle to define a model that seems appealing for the Arab region overall.

The endurance of regionalism also carries with it hope. Ideas about political or social improvement that cross national borders have the potential to build popular support as they did when the Arab uprisings spread. A regional lens on broad economic and social problems that is not mired in polarizing ideologies could allow imaginative Middle Easterners and outsiders to bypass the limits or authoritarian tendencies of many national governments.

Pan-Arabism remains an ongoing reference point, however vague or romanticized it can sometimes be. The real challenge facing the Arab world is how to use this regionalism to fashion workable political and socioeconomic approaches that can concretely better the lives of the majority of people in the Middle East.