Patrick Modiano is out. Who knows where. The Nobel Committee couldn’t find him before they had to make public the news that he is the 2014 Nobel laureate in literature. With absence a major presence in his writing, this couldn’t be a more fitting response to the award. It is in the same league as Doris Lessing’s complete refusal to play the thrilled recipient in 2007.

“I feel like I have been writing the same book for the past 30 years”, 69 year-old Modiano said in 2001 in an interview to Le Monde, reflecting on a body of work that even at that point spanned more than 20 novels. His writing has repeatedly circled around biographical material, particularly focusing on the French Occupation and the blind-spots of memory. As he writes, he also reflects a great deal on his own experience of writing. This is part of a typical French tradition of interweaving autobiographical fact and fiction into a kind of “autofiction” that draws on the power of literary writing to uncover the hidden truths of our lives.

There’s a trend here. In recent years, the Nobel Committee appears to have been on a mission to reward representatives of absence and marginality: Herta Müller, the 2009 laureate, was praised for giving a voice to the dispossessed, while Alice Munro raised the profile of both the Canadian provinces and the understated short story genre in 2013. Now Modiano has been added to this list “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation”.

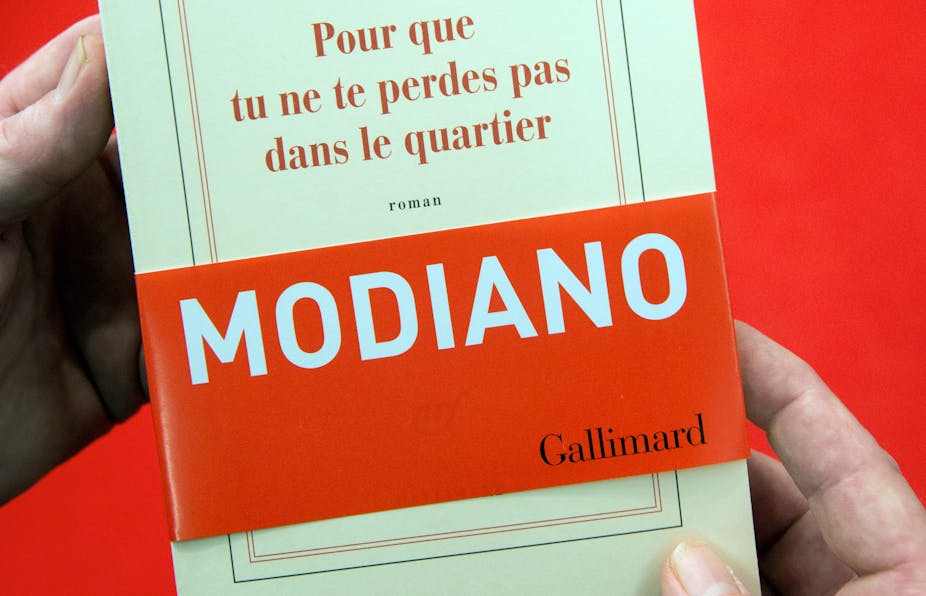

But as a writer Modiano has been anything but marginal. In fact, he’s been everywhere in the French world of letters. Not only has he gathered in all the major national prizes during a career spanning four decades, written the screen play for the blockbuster film Lacombe, Lucien, and amassed an unusually broad-based readership for a literary author. In 2013, he was also one of the few writers to be admitted to publisher Gallimard’s prestigious Quarto series while still alive.

The ten novels gathered in this volume form the backbone of his literary oeuvre and the texts are accompanied by lavish visual and autobiographical textual documentation – despite the author reputedly shunning the media and disliking the “autobiographical pose”.

But how many English-speakers had heard of Modiano this morning? It won’t have been many. Only 3-4% of the total UK and US market in literary fiction are foreign-language books translated into English.

Gallimard’s 1,088 page investment in their author – staggeringly cheap and accessible at €23.50 – will more than pay its way over the coming months in the Francophone world. But who will be pushing Modiano to a global audience – especially if the author himself is as media shy as he claims?

This is where the Nobel Committee need to spare some thought for the laureate’s translators. At present, only a third of Modiano’s works are available in English translation, but he is much more comprehensively available in German and Spanish (and this is only to mention the major European languages). In some cases, these translators are well-regarded authors in their own right – the Austrian Peter Handke, for example, has been a potential candidate for the Nobel Prize himself.

Literary translation is an intellectually rewarding, but gruelling and insecure job from which only a tiny minority can make enough money to live. And yet now, when suddenly the whole world wants to know about Modiano, shouldn’t they also be hearing about his translators? These women and men (and it must be said the majority of translators are women) will in fact be Modiano’s voice in the text.

Over the coming weeks and months, many of them will be scurrying to help promote and explain their author to non-Francophone audiences around the world. They will barely get an official mention anywhere. The world will listen to them, but not hear them, read their words, but not see them, celebrate their author, but not know their name.

If the Nobel wants to acknowledge the dispossessed and the marginal, it should also reward translators.