After almost two years – and an extraordinary global hiatus whose impact remains as yet unclear – it is inevitable that many will write about COVID-19 for decades to come. Indeed, one of the first books – Spike, by Jeremy Farrar, one of the UK’s leading scientists and a member of the Sage emergency committee – has just been published. As we enter a long period of reflection, arts and humanities scholarship has much to offer, especially once the intensity of scientific and medical coverage has begun to subside.

Early on, as many of us locked down and worried about how we would emerge from the pandemic, the only chapter of any book on COVID any of us wanted to read was the one on the vaccine. Would there be one and would it work? But the technical description of this precious medical intervention in publications to come will be concise and short. The fuller story lies elsewhere.

The medical history of plagues is fascinating, but it is seldom the critical issue. We don’t know for sure what the Athenian plague of the fifth century BC was, or the devastating plague of the second and third century AD. The plague of the sixth to eighth century AD in the Roman empire is a matter of some discussion but was probably several different infections. We know how the Black Death was spread, but it’s scarcely the most interesting thing about it.

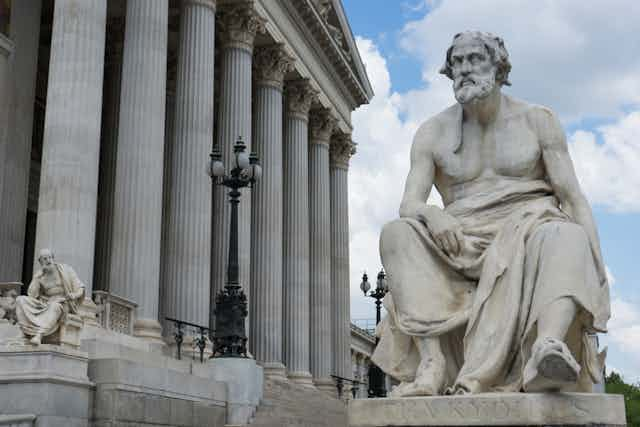

What is more interesting is how people react to plagues and how writers describe their reactions. The account by the Greek historian and general, Thucydides (460-400BC), of how the Athenians responded to their virulent plague in the fifth century, directly or indirectly influenced how many later historians in antiquity described plagues. It set the pattern for a narrative of symptoms alongside social impact.

Athens was in the second year of what would turn into more than 20 years of conflict with its Greek rival Sparta. The plague spread rapidly and killed fast – its symptoms beginning with fever and spreading through the body. Some Athenians were dutiful in caring for others, which usually led to death, but many simply gave up, or they ignored family or the dead, or they chased pleasure of every kind in what time was left to them.

How far the plague changed Athens is debatable – it did not stop the war or affect Athenian prosperity. What Thucydides does say is that the loss of their great statesman Pericles (495-429BC) to the plague altered the nature of their leadership, and removed some of its moderating features. It is left implicit that the Athenians may have abandoned more of their traditional piety and respect for social norms.

This was the generation that would produce the most radical questioning of the role and nature of the gods, of what we know of the world and how we should live. But it also led to a renewed sense of militarism and eventual catastrophe: Athens’ defeat by Sparta and the loss of her empire.

Pandemics and their impact

The temptation is to say that pandemics change everything. The Byzantine historian Procopius (AD500-570), who survived the onset of plague in the sixth century AD, was alive to this. Everyone became very religious for a while, but then as soon as they felt they were free, they went back to old behaviour. The plague was a wonderful symbol of systemic decline, but people adjust.

Was the Byzantine world so fatally weakened by plague and its resurgence that it was unable to resist the onslaught of the Arabs in the seventh century? This may well be partly true, but the plague significantly preceded the Arab conquest, there was as much continuity as disruption visible in their culture and city life, and the Arab world had its own pestilences. History is not so simple.

So what of our own pandemic? What will it change? Tempting as it is to predict a complete overturning of social behaviour, the lessons of the past would suggest that this is unlikely. The strong bonds of society have survived well.

Perhaps the worst consequence is how this has set back progress in the developing world.

That, and long-term mental health and educational impacts across the world, are exceptionally difficult to gauge – though this will be the most studied pandemic in our history. And it will be arts and humanities scholars and social scientists who will be doing much of this incisive work – and already are. For example, The Pandemic and Beyond at Exeter University is already mapping more than 70 COVID-19 projects in the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s portfolio.

Pandemic science

So what does history tell us that is useful? Look harder and dig deeper. That’s why the history of COVID won’t just be the description of the virus and vaccine, or the mystery of whether it came from a bat or a lab. It will be the immensely complex story of how this disease intersected with our social behaviour, how we chose to respond as individuals and families, communities and politicians, nations and global agencies.

What the best historians from Thucydides on have told us is that the biology of disease is inextricable from the social construction of illness and health. And we also see that humans are very bad at thinking about consequences.

One of the most interesting potential consequences of this pandemic is the relationship between politics and science. The Athenian plague may have jolted thinkers to be more radical by questioning traditional views of life, death and the role of the gods. And the Black Death is often seen as gamechanging in terms of religion and philosophy, and encouraging changes to medical ethics and improvements in social care. It even changed the balance on the value of labour, but we have yet to see if our pandemic has lasting inroads into patterns of working in offices or virtually.

This latest pandemic has shown science at its best and most essential, but it has also placed it uncomfortably centre stage in political decision making. Alongside the much more dangerous climate crisis, the pandemic has encouraged politicians to claim to “follow the science”. But science does not speak with one voice, seldom offers easy or unequivocal answers and resists the short term. How the conversation between politics and science plays out, and what the consequences of the trade-offs may be, might yet turn out to be one of the surprises of this strangest of moments.

In the long run, understanding the impacts of this virus – and the wider cultural, social and economic challenges in which it is embedded – will require us to deploy a more generous and holistic view of science. Only in that way will we write the account of this pandemic that its disruptive force demands.