The carnage in Melbourne’s CBD on Friday, in which five pedestrians died after being hit by a vehicle driven by a wanted offender, has again highlighted the issue of police pursuits.

Any policy governing police pursuits must balance the need to apprehend offenders with community safety. So what is the appropriate balance? And have Australian jurisdictions got it right?

The inherent problem with police pursuits

Police pursuits are among the most challenging operational situations facing officers. These decisions involve life-and-death outcomes and must be made quickly, under stressful conditions.

Such decisions will often be dissected later in great detail, and with the benefit of hindsight. As a Victoria Police report on pursuits said:

The fallout public opinion and media commentary that follows a pursuit indicates it truly is the case of damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

There is no standard definition of a police pursuit in Australia. But an Australian Institute of Criminology study applied the following definition:

A police pursuit is an active attempt by a law enforcement officer operating a motor vehicle with emergency equipment to apprehend a suspected law violator in a motor vehicle, when the driver of the vehicle attempts to avoid apprehension.

How common are pursuits and deaths?

An Australian Institute of Criminology study identified that in 2009 there were 3,806 pursuits, in 2010 there were 3,865 pursuits, and in 2011 there were 4,175 pursuits across Australia. The study noted that less than 1% of pursuits resulted in a fatal crash.

It identified that between 2000 and 2011 there were 218 deaths in 185 crashes. Of those killed 38% were bystanders, while the other 62% of deaths involved the driver or passenger of the pursued vehicle.

Traffic matters and stolen motor vehicles were the most-common offences prior to a fatal pursuit being commenced.

In Queensland there were 148 pursuits in 2014-15 and 135 in 2015-16. Only 3% of these were for matters concerning imminent threat to life, or homicide.

Estimates in the US suggest one person dies every day as a result of a police pursuit. One news source claimed that between 1979 and 2013 there were 11,506 pursuit-related deaths in the US. Of those deaths approximately 1% were police, 55% were suspects and 44% were bystanders.

Pursuit policies

In general, police pursuit policies could be described as those that are liberal – in that they allow officers a large degree of autonomous responsibility in deciding to continue or stop the pursuit – and those that are restrictive, which impose strict criteria that need to be satisfied before engaging in a pursuit.

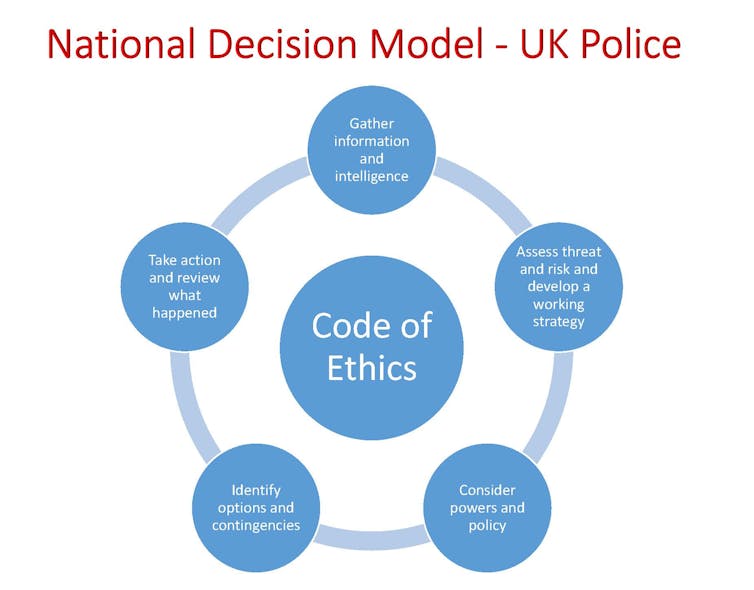

In the UK, police services rely on the National Decision Model risk management tool to decide whether a pursuit is justified. This type of policy has the advantage of providing a simple, robust and consistent policy tool for police to use in a variety of situations.

Despite impressions to the contrary in the media, the US has moved toward more restrictive policies.

In Australia, there has been a general movement toward more restrictive pursuit policies as police services seek to reduce their exposure to risk.

In 2016, as a result of a report into police pursuits, the Australian Capital Territory restricted pursuits to when there is a serious risk to public safety, or in relation to a major crime involving the injury or death of a person.

Do restrictive policies work?

To complement the more restrictive pursuit policies, there are moves to create offences or increase penalties for those who seek to evade police.

In simple terms, the theory is to let offenders flee and catch them later. This policy is only effective if you actually charge the offender with the offence at a later date.

In Queensland in 2016 there were 5,018 incidents of evading police. But just 43%, or 2,180 cases, resulted in someone being charged. Of more concern was that the number of incidents of evading police increased by 36%, up from 3,695 in 2015. It could be argued that offenders are learning that, by not stopping for police, they will never be brought to account.

In 2012, Western Australia introduced tough new laws for those who evade police, with mandatory sentences. But despite this, pursuits have increased.

There is also now a push by the WA opposition and the police union to allow police to ram fleeing vehicles.

Consistency is key

One of the problems with restrictive policies is that there must be consistency in how they are applied.

Recent examples in Queensland have highlighted this inconsistency. In one instance, an officer doing in excess of 200km/hr in pursuit of an offender was stood down and disciplined. Yet in 2016, it was claimed that a police motorcyclist reached speeds of 200km/hr on a major highway during a pursuit, but only received guidance.

There is also the case of two Queensland police officers currently before the courts on charges of dangerous driving for allegedly continuing to pursue offenders wanted for violent armed robberies, despite the pursuit being terminated by senior officers.

WA introduced new laws aimed at protecting police from criminal charges after an officer killed a bystander during a high-speed pursuit.

In contrast, in 2015 New South Wales police were angered by the apparent failure of their counterparts in Queensland to stop a long-term pursuit of armed offenders entering their state due to policy restrictions.

Future directions

After reviewing its safe driving policy in the wake of pursuit-related deaths, NSW police were criticised for not releasing the updated policy.

Victoria Police has been similarly criticised in the wake of the Bourke St deaths for not releasing its pursuit policy. Its reasoning is it did not want to educate criminals on how to evade police. But such reasoning is infantile. There must be transparency on policies that have such an impact on life-and-death situations involving innocent members of the public.

While Victoria Police’s actions in last week’s events will be examined, the aim should not be to lay blame, but rather improve the tools police have at their disposal to deal with highly fluid and dangerous events. After all, policing is not an easy job.