In this episode of Politics with Michelle Grattan, former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull gives his frank assessment of Scott Morrison as a former colleague and as prime minister, warns about the right of the Liberal party, and tongue lashes News Corp.

As Treasurer, Morrison at times infuriated then PM Turnbull by leaking to the media and “frontrunning” positions before decision were made.

“Morrison and I worked together very productively” but “he had an approach to frontrunning policy which created real problems for us,” Turnbull says.

As for now, Morrison’s “obviously got massive, completely unanticipated challenges to face … I think he’s doing well with them by the way. … I think the response of Australian governments generally [on coronavirus] has been a very effective one”.

Turnbull’s anger against both the Liberal right wing and News Corp continues to burn undiminished.

The right, “amplified and supported by their friends in the media, basically operate like terrorists”.

News Corp “I think was well described as ‘a political organisation that employs a lot of journalists’”; The Australian “defends its friends, it attacks its enemies, it attacks its friends’ enemies, and the tabloids do the same.”

Transcript (edited for clarity)

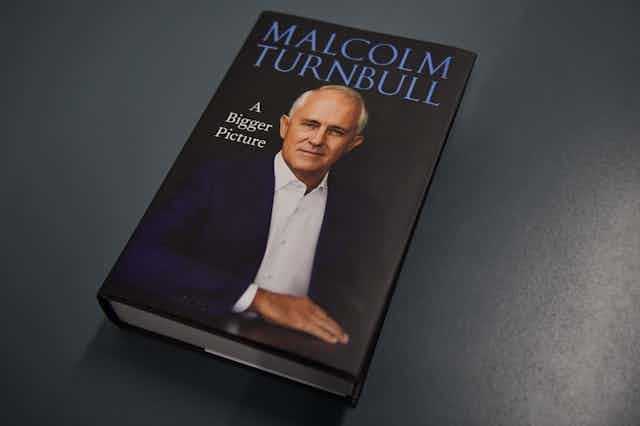

Michelle Grattan: Malcolm Turnbull’s memoir was much anticipated. Even so, its landed with additional fanfare. This is thanks to copies being distributed ahead of publication by a Scott Morrison staffer, who’s been threatened with legal action by the book’s publisher and has since apologized.

The huge tome covers Turnbull’s event filled life before politics, but most interest is in his parliamentary years, which included losing the leadership in both opposition and government. In each case, while the reasons for his downfall were multiple, his fight for more action on climate change was central. In his book, Turnbull is frank about his former political colleagues, including Scott Morrison, whom he both praises and damns.

Within the Liberal Party, Turnbull has always been a controversial character. For his supporters, he’s a small L liberal progressive who stood up for the right causes. For his detractors, he’s a Labour man in big L Liberal clothing who has undermined the party. Feelings haven’t changed since he left politics. Malcolm Turnbull joins us today remotely, of course.

Malcolm Turnbull, firstly about the leak of your book, your publishers have threatened to take legal action against the Morrison staffer concerned. Will this action go ahead?

Malcolm Turnbull: Well, that’s really a matter for them, Michelle, it’s a very big issue in the publishing industry, as you know, and all of the creative industries, you know, internet, copyright piracy is a crime. I mean, if you you know, if you distribute pirated copies of a book or film or a song, you’re stealing just as if, you know, shoplifting from Dymocks. So it is a serious matter. For them it is really a big issue of principle, but I’m leaving that to them. Obviously, it’s rather awkward timing, given that the government’s out there in the press today talking about how it’s going to take steps to ensure that Facebook and Google pay money to newspapers for the use of their content and talking up the sanctity of copyright, and at the same time, someone in the prime minister’s office is distributing, as he’s admitted, at least 59 copies of the book in breach of copyright.

MG: Now, just on this question of the timing of the book’s release, the timing is somewhat difficult. How does one do a virtual book tour? What are you doing exactly?

MT: Just like this, you know, just doing a lot of Zoom meetings, large and small and podcasts like yours. And so I’m doing all this from home, with occasional excursions to studios like at the ABC last week where we recorded an interview with Leigh Sales and myself, and you know, in a vast hall with everybody metres apart. So it was a rather unusual environment, but that’s what you have to do.

MG: Now just to get to the substance, you document in the book your battles over climate change, which ended in personal disaster for you, not just on one occasion, but twice. Looking back, do you think you could have done things any differently to have achieved more success on that issue and at less personal cost?

MT: Well, you know, if you look back at what I did in 2018, you can see that I was very consciously learning from the experiences of 2009. So I was very careful to keep the cabinet together. I consulted the party room very carefully. The National Energy Guarantee, had the widest support of any energy policy I can recall. And no one could have said I was high handed or, you know, heavy handed. I was very, very consultative and clearly had the support of a substantial majority in the party room. But that did not stop a minority basically using it as a means of destabilising the government, both to get their own way on climate and also to undermine my leadership. This was all part of the, you know, the Dutton coup which ended much to their dismay and Scott Morrison becoming prime minister.

MG: So where do you see Australia’s policy on climate going from here? There’s been speculation, of course, that the bushfires might have been a game changer, but is that really likely? And on the otherside, of course, the coronavirus has had the effect of bringing a short term hit to emissions. But what about the longer term?

MT: Well, the obstacle to effective action on climate change in Australia is entirely political. The community, the business community, you know civil society are by and large united in their determination to move to a zero emission energy sector and net zero emission economy. However, there is a determined minority, I think it’s still a minority, that may become a majority depending on how far the Liberal Party moves to the right. But there is a determined minority within the Liberal Party and the National Party supported by obviously the fossil fuel lobby, but above all, by the right wing media, in particular Murdoch’s media, which has resolutely opposed taking action on climate change. And so, you know as I record in the book, we had during December and January, during these terrible fires, we’d have on one page the News Limited tabloids, pictures of the most terrible destruction and facing them, attacks on Gretta Thunberg or anybody else types climate change seriously. So that is that that is the roadblock. I mean, you remember back in 2007, when both John Howard and Kevin Rudd supporting an emissions trading scheme. You know, it was a bipartisan policy, well Abbott weaponized climate change as an issue. He was backed in by elements of the media and we are where we are. So I think it’s absent a change inside the coalition, I don’t think we’ll get any progress on this any time soon.

Now, you know, one of the the disappointments I’ve had with the Morrison government is that Scott did not take the opportunity after his miraculous win in May to reinstate the NEG [National Energy Guarantee]. Cause Scott believes in it, I mean, he absolutely was on board with that as was Josh. It was absolutely a joint effort they’ve got as much handy work in it as I have. In Josh’s case possibly a bit more. But you know, at that moment, when his political capital was, as you’d agree, you know, at its absolute zenith, he still wasn’t prepared to do it because, I guess he knows, that you know, right wing group in the party room would, if they got the chance to do the same to him as they did to me.

MG: Well, just talking about that group, it is a minority, I would have thought. Surely, most of the Liberal MPs are pretty pragmatic. When you became prime minister, did you think initially that the party would settle down after the coup or did you, in fact, under estimate the determination of your opponents?

MT: Yeah, I never you see, I never, you know, calculated or considered the possibility that there would be a group within the party that would seek to destroy the government and cause us to go into opposition. And but you know, that was Abbott’s agenda. And as Rupert Murdoch has admitted in his discussion with me in that coup week. That was Paul Whittaker’s agenda, or Bill Borris, as he’s better known as the most senior editoral executive at News Corp in Australia, very close to Lachlan. And they had this crazy agenda to bring down my government in the expectation this would result in Shorten winning an election so that Abbott could come back as opposition leader after the election. I mean, it’s completely crazy, but that, you know, that’s why so many people said at the time, and you know they’re identified and quoted in the book that the right’s concern was not that I’d lose the election, but I’d win it. Now, you know, that’s trying to provide a rational analysis of that is very difficult. I mean, you’ve been around politics for longer than me, Michelle. I’ve never seen anything as mad as that. There it is. You know, that was that was their agenda.

MG: Looking back or reading back over those years in your book, one is struck by the fact that there was a lot of bad behaviour by a number of people. How much responsibility do you yourself take for some of that bad behaviour?

MT: I’m not sure what you mean by that. I mean, I take responsibility for my own behaviour, but I can’t take responsibility for others.

MG: Well, I mean, there was a lot of undermining of people by others, by their colleagues.

MT: Whom by whom? Who are we talking about?

MG: Well, I think a number of the the leading characters in the book and surely you would agree that you were part of the maneuverings of those years sometimes to your advantage, sometimes to your disadvantage.

MT: You’re being uncharacteristically obscure, Michelle. But let’s look at Abbot. I mean, Abott’s government’s problems were created by Abbot and Credlin, not by me. Not by me. In fact, as I describe in the book in some detail, there are a number of messes that Abbott got himself into that I ended up sorting out whether it was the citizenship deprivation fiasco, which was all that. Or you remember the meta-data fiasco. You know, basically Abbott kept on making knee-jerk decisions without proper preparation, without proper consultation, with the predictable consequences. And on a number of occasions I basically cleaned them up, for which I got scant thanks. Or no thanks, of course. So, I mean, look at the fiasco over gay marriage. I mean, what an extraordinary shambles that was. I mean, any normal government. I mean, Abbott had said to the party room, you know, when she raised in the party room, he said, “look, we’ll take it to a leadership group and that cabinet will consider it, and We’ll come back to the party room” and everyone oh well that whats sense, that’s what you’d normally do. Instead, we had this sudden party room meeting called, and everyone is invited to stand up and give ex tempore speeches about what they think should be done. It was like complete bedlam. I’ve never seen anything crazier than that. And, you know, so that did him a lot of damage. That was his doing. I mean, I didn’t tell him to make Prince Philip a knight. I didn’t tell him to give Simon Benson the outcome of the cabinet meeting before it was held up on citizenship, what a joke that was. You know where Benson had a story the morning after the cabinet meeting saying last night the cabinet decided X, Y, Z. Well, the cabinet hadn’t, actually, but he’d been briefed by Abbott’s office before the meeting. How ludicrous.

MG: A lot of what you write, of course, is very close up and personal to conversations and interactions between the various players. When you were writing, did you worry about breaking confidences? How did you navigate that line?

MT: Well, look, it’s it’s really just a question of judgement, Michelle. You can’t write a political memoir without talking about what actually happened. And so you do need to, you have to, every diarist, every memoirist, if that’s the right term, has to talk about discussions and events. It wouldn’t be much of a history if I hadn’t done that. But I have obviously used my discretion and there are things, you know, naturally have been said that have not been repeated. But, you know, I think if you were to look, I mean, particularly someone like yourself that has been in the press gallery for a long time. I mean, you know, I know there have been people saying, oh, it’s terrible to describe Scott Morrison’s front running on tax policy and that that was a problem for the government. I mean, everyone in the gallery knew that. I mean, there’s literally I mean, that the setting it out in the way I did maybe will be of interest to many people, no doubt. But it’s a fact and hardly a surprise. I mean, you understood, that it was obvious. You know like it was the subject of public culture at the time.

MG: Now, you obviously kept a diary of key events, did you keep that diary all through?

MT: Yeah, I did, intermittently. I mean, I didn’t keep it every day. And I did yeah. I did keep contemporaneous records. I mean, I wish I’d kept more because it’s quite interesting, when you’re writing a book and you go back, you’ll see in your diary accounts of an event that absent the diary, you have very little recollection of. Memory is very frail. And so there are, you know, obviously the episodes that I can most effectively and colourfully recount of those that I’ve got contemporary records.

MG: It’s not quite as comprehensive as that of the former Labour minister, one time Labour minister the the late Clive Camera. But still, you do seem to have kept quite a lot.

MT: Yeah, well, it’s it’s look, I mean, there are gigantic [UI] stories. You know, let’s face it, you know, there is no substitute for contemporary evidence and I mean and diaries four people, 40 people can go to a meeting, have a discussion and then come out of it with slight, each age with differing accounts. You know, I’ve seen particularly when I was a lawyer, I’ve seen, you know, examples of that. But when I say differing accounts, I mean honestly, differing accounts. But having said that, history is made up of recollections and memories and records. And that’s why it’s important to pull them together.

MT: I might just add Michelle, as you know, it’s not as though people in politics have not, you know, briefed out conversations with me, WhatsApp messages from me. I mean, I’ve read, you’ve seen them yourself, I’m not sure ifyYou’ve written any of those stories, but you’ve seen plenty of occasions where things I’ve said or alleged to have said have been published, you know, there’s some value in putting your name to it. As I have, this is my book and actually telling the story as it happened, I mean, if people want to dispute that, they are free to do so, and no doubt will.

MG: In the book you seem to me to have a quite ambivalent attitude to Scott Morrison, you portray him as a leaker and one who used the media to try to lock colleagues in over policies, the so-called front running technique. Yet you also thought that you had an effective working relationship as prime minister and treasurer. Which is uppermost in your recollection now? The bad Scott or the good Scott.

MT: Well, look there’s no bad or good Scottt, T. tHere’s just Scott, right. And he has strengths and weaknesses as we all do. I did have a good working relationship with him. The only problem, quote unquote, I had with Scott was his front running of policy. And look he didn’t deny it. You know. Well, you know, sometimes he claim that particular things, he had no idea how they got into the media, but no-one was particularly convinced by that. But, you know, Scott, it was a technique. He saw this as a way of front running, floating ideas and policies and [UI] and, you know, it was completely antithetical to my approach. And as I said at the time, as I’ve described in the book, you know, the problem with running your policy agenda through a series of hypothetical thought bubbles in the tabloid press or any press, is that, you know, you run the risk that they get shot down in flames before you’ve formulated them. They can, you know, become, run off like hares across the countryside and get out of control and significantly, and this is the major problem that we had, we paid a high political price for this. People will, if you fly half a dozen ideas in the media. And then let’s say for perfectly good reasons, don’t go ahead with them. You look as though you’ve backed off, walked away, reneged or something, and you may be seen or backed off or abandoned the policy that you were never likely to accept anyway. You know, as I say in one message to Mathias. You know, the approach that he and I had was that we should stick to whatever policy we have until such time as we decide to change it and then change it. As opposed to having policy A. But then tentatively floating that you might move to B,C,D. I mean, look, there are people in Canberra who have defended Scott’s approach. That they think that’s a sensible way to proceed. I honestly don’t, you know, the most effective policy measures that we had and the school’s policy, the so-called Gonski 2.0 is a very good example of this, where we did a lot of work in private, kicked around a lot of possibilities, went uphill and down dale on them and then made a decision and then announced it. And, you know, I don’t have a problem with all of the options and the consideration that preceded the announcement being made public, you know, at some point, even relatively quickly. But the difficulty is that if you are literally thinking aloud, it honestly undermines effective government, in my opinion.

MG: Do you think he’s still front running policy?

MT: Ah look, I’m not quite, I don’t know, I couldn’t I’m not. You’d be better able to say that Michelle, you’re there in the gallery keeping an eye on things that, you know, he’s obviously got massive, completely unanticipated challenges to face at the moment. I think he’s doing well with them by the way. You know, I think the response of Australian governments generally has been a very effective one.

MG: On the virus, you mean?

MT: Yeah, absolutely yeah. I mean, look, there have big mistakes have been made and, you know, they’re feeling their way. And no one really knows for sure what the right, you know, right measures are, which measures are more effective than others. But collectively, the states and the territories and the federal government have been doing a pretty good job. And, you know, touchwood, let’s hope that they continue to do so.

MG: One of your main initiatives as prime minister was the legislation against foreign interference in response, particularly to fears about Chinese interference. Do you feel that legislation is doing its job?

MT: Well, I have heard, well I’ve seen complaints that it is not being properly enforced and that in particular the transparency legislation, which was it’s, you know, that there were two, there was a whole bundle of bits of legislation, but essentially there was one about foreign interference, which basically dealt with espionage and people trying to coerce others to, you know, take particular approaches in terms of public policy and so forth. But then there’s the transparency legislation, which we talk about as foreign influence. Our position there that we didn’t mind if foreign governments or foreign state owned companies or political parties wanted to seek to have influence in Australia, but they had to do so transparently, so essentially a sunshine policy. Now, there’s been, I’ve seen people say that it hasn’t been adequately enforced. Look, you know, in the face of a lot of controversy and criticism, I was able to ensure that those tools were created, and it’s really up to the government to make sure they use them.

MG: But you’re worried about that?

MT: I wouldn’t, I’m not, well I am, my concern is that is that the Australia’s democratic processes should be determined by Australians.

MG: And you still you still think that threat is there?

MT: Well, of course, the threat is there.

MG: Well, perhaps not being adequately met.

MT: No, no, I’m not saying that Michelle, that’s what you’re trying to get me to say. I’m really asking you, you you’re much closer to it, whether you think that is the case? I have seen people complaining and criticising. It’s effective…whether it’s being effectively measured, but others would be better able to express a view on it. So there it is.

MG: Now you obviously have a lot of complaints about your treatment by News Corp, but more generally, do you think there needs to be reform of the media in Australia and what form should that take if you do?

MT: Well, you know, there’s I mean, we have free a free press in Australia. But I think we have to recognise that News Corporation and I think this may well will reflect Lachlan’s influence because he is a much more right wing person, much more ideological political person than his father, which is saying something. But News Corp is I think was well described as a political organisation that employs a lot of journalists. I mean, it isn’t you know, the Australian is not. You can’t compare the Australian, describe the Australian as a newspaper with a product of journalism. I mean, it you know, it defends its friends, it attacks its enemies, it attacks its friends enemies and the tabloids do the same. I mean, look at that, just leaving me aside. Look at the extraordinary attack on Matt Kean. Remember when Matt Kean, the young environment minister, gave a perfectly fine, you know, I would say mundane is not the right term, but it wasn’t full of surprises. He gave a sensible speech about climate policy. And he was rewarded for that with the most vicious attack from The Daily Telegraph, you know, claiming that he was, you know, the personal attack of claiming that he was posing as a volunteer when he wasn’t. You know, it’s just classic tabloid hit. And, you know, the you know, I don’t think that News Corp any longer hold governments to account. And the question is, who is holding News Corp to account? You know, this is the real challenge is operating as a political organisation. And, you know, the the thing is that they, as I say, well, it just isn’t, it isn’t remotely any longer what you would call a proper newspaper, the Australian and the tabloids. They are basically political weapons. Of course, they still report news, thay have to do that. But it is, it’s very much a political orientation. I mean, do you disagree with that?

MG: Well, that’s perhaps for another time.

MT: So well Michelle, let me ask you this just as, here’s an important question for you. So you’ve been in politics and journalism for a very long time. Why aren’t you prepared to say what you think is going on in the Australian media? You’re better able to talk about it than I am.

MG: Well, I think, as others might say, we’ll take that as an observation rather than a rather question to be answered.

MT: No but seriously. This is an important question. What a-feared of? I mean, you, nobody has… How long have you been in the press gallery? Is it 40 years?

MG: Longer than I care to say I think.

MT: You’ve have seen it. You’ve seen it. You would have started in the press gallery not long after the Australian was founded, as a newspaper. And so you’ve seen it all and you’ve seen how it’s changed. But you’re not prepared to have a discussion about it.

MG: Perhaps not on this interview. Moving right on, some of your enemies would like to see you expelled from the Liberal Party. Do you still see yourself as a loyal Liberal? It’s a big L loyal Liberal and what do you reply to those people?

MT: Well, it would be ironic if the party of free speech expelled someone for writing a book. Well look, I’m a member of the Liberal Party and I am proud to be so. I would be surprised if there would be much enthusiasm for expelling me from the party. But I’m not, you know, when you when you consider the way in which, I mean, what I’ve written is essentially, is an account of my life. It’s essentially a work of history. In so far it’s about politics. But when you consider the way some members of the Liberal party savagely and often publicly sought to undermine and bring down my government, it is ironic that many of them are now supporting my expulsion from the Liberal party. Puzzled why they didn’t try to expel him from the Liberal party when I was prime minister.

MG: Where do you see the party heading in the next decade? And who do you see as those who can carry it forward successfully?

MT: Well, as you know, the premise of a political party is a broad church, big tent political party, is that you work by consensus. So that means that you have, you know, people on the left and on the right and in the middle. And some people will be on the left on one issue, on the right on another, and you know, get a diversity of opinion. And the idea is that people debate these issues, they kick them around, and then the consensus or majority, however you want to describe it prevails. And that’s the deal. Now, basically, the situation we’re in with the Liberal party is that theright and so I’m talking about Canberra in particular, the right are amplified and supported by their friends in the media, basically operate like terrorists, I hasten to add, they’re not using guns and bombs. But their proposition is if you don’t do what we want, we will blow the joint up. And that was absolutely the way they operated in 2009, and certainly the way they were operating during my prime ministership. I mean there were you know, the coup in August 2018 was not the first one. Remember at the end of 2017, there was a whole move to use Christiensen to, you know, when we had Barnaby and John Alexander out of the house, and didn’t have a majority for a few weeks. Christensen was going to cross the floor or bring down the government unless I resigned as leader, and that was all being cooked between Andrew Bolt and Peta Credlin. I mean this is all public, you know, public knowledge. It’s been reported on. And Christiensen for some reason or other backed off it. But you had Jones inviting Kerry Stokes to his house at the end of 2017 with Abbott and saying, we’ve got to bring down Turnbull. And so forth, you know, this was this was their agenda was to basically terrorise the party room, terrorise the government until they brought it down, in which case they would lose an election and Abbott would come back as opposition leader. This is the scenario that Paul Whittaker at News Corporation, according to Murdoch, subscribed to - just staggering and yeah, and that’s that’s how, that’s how they operated. But it was you know, I’m not telling you anything you don’t know. I mean, I hope, you know that at some point you’ve got to say, you’ve got to describe the facts, Michelle. And the emperor has no clothes, say so.

MG: Do you see any bright lights in it for the future in the party?

MT: Well, I think if you mean bright lights, individuals, yeah, there’s lots of talented people there. Sure. I think Josh Frydenberg was very good young treasurer. I think Morrison’s doing well. Look, Morrison and I are not, you know, we work together very productively. He had an approach to, you know, front running policy, which which created real problems for us. And I think that damaged us. But I’ve I’ve said in the book others would have a very different view that I did not think he was doing it deliberately to damage the government. He just, he, you know, he this is how he had this sort of strange relationship particulary with News Corp where he was always like bringing, you know, making them a kind of a collaborator in the development of policy through the pages of the newspapers. It was a bit bizarre. Anyway, so Morrison well, he’s obviously, he’s you know, he’s at the top. I think there are, you see a lot you see a lot of smaller liberals in leadership positions in the states, you know Gladys in New South Wales. Steven Marshall in the South Australia, I think that the challenge, though, is the way the right operates, that, they have been able to succeed through this process of intimidation and that will drive more moderate people out of the party and so the minority can then become the majority. But it certainly means that the party is, you know, is operating, runs the risk of operating to the right of, you know, where the public is. This is, this is a risk. I mean, you’ve seen this in in the past, you know, with the Labour party’s membership and union leadership has gone too far to the left and got out of step with the public at large. I mean look at the UK with Jeremy Corbyn. You know, he had overwhelming support of the British Labour party. They loved him. And what happened? It was entirely predictable. It’s just, you know, you had a government that had been in complete disarray and they had a landslide win. And you can’t take any credit away from Boris Johnson, but boy, Corbyn made it very, very easy for him.

MG: Now the book’s done and dusted, will we hear the Turnbull voice in the big national debates of the coming years to a great extent?

MT: Well, you’ll, you’ll, you’ll. Yes, you will, from time to time. Yeah, sure. I mean, I’m not, I’m not planning to run for parliament again, I can assure you of that, But I you know, as I as I say in the, I’m just picking up my book, which are encourage your listeners to acquire, legally, I say here:

“While I was determined to leave parliament, my time as PM was over. I haven’t lost interest in politics and public affairs. In particular, I remain committed to an Australian Republic and above all, to seeing effective Australian and global action to cut our emissions and address global warming. Now that the 2019 election is over, I’m free to play a more active role in public life. I’ve surrendered the title of Prime Minister, but I retain the most important title in our democracy, an Australian citizen with all of the responsibility and opportunity that entails.”

MG: And what about other plans?

MT: Well, I mean, I’m in business. I mean, I’m not gonna start another investment bank or anything like that, but I’m investing actively in a number of areas, but in particular in venture capital and particularly in Australian technology. I mean, the announcements of my investment in Myriota an Australia, sort of small satellite company, I’m just dealing with the stuff that’s publicly known. I’ve invested in advance navigation, a leading Australian technology company in the area of, you know, in effect, they create, make, virtualized gyroscopes that enable you to have, you know, essentially automated immersion navigation, which is a very in other words, navigation without using GPS or satellites. Add there’s a bunch of others. So, yes I’ll continue doing that. That’s what I used to do in the past. And I love being involved in technology and innovation. I think it’s just such a big part of my political agenda, but it’s a great passion of mine and so critical to Australia’s prosperity and security in the years ahead.

MG: It’s been really good to talk to you. Malcolm Turnbull, but I just have one footnote question. I understand you’ve provided your own audiobook reading. Does this include a return to your 2017 mid-winter ball Trump impersonation?

MT: Well, it wasn’t really a Trump… yes… well, that’s a little you’ll have to buy it and listen. No but was very he was very complimentary about it. It wasquite funny, it was more of a Trumpian speech than a Trump impersoniation. But I I do. I did. I did enjoy that. It was the last so-called off the record mid-winter ball speech wasn’t it, because Laurie Oakes decided to publish someone’s smart phone recorded version of it.

MG: It’s true that they’re not so much fun on the record.

MT: That’s right, I’m told ever Peta Credlin laughed when I gave that speech.

MG: Malcolm Turnbull, thank you very much for talking with us today.

New to podcasts?

Podcasts are often best enjoyed using a podcast app. All iPhones come with the Apple Podcasts app already installed, or you may want to listen and subscribe on another app such as Pocket Casts (click here to listen to Politics with Michelle Grattan on Pocket Casts).

You can also hear it on Stitcher, Spotify or any of the apps below. Just pick a service from one of those listed below and click on the icon to find Politics with Michelle Grattan.

Additional audio

A List of Ways to Die, Lee Rosevere, from Free Music Archive.

Image:

Mick Tsikas/AAP