“Revolt begins where the road ends.” This sums up the thoughts of a Portuguese general on the counterinsurgency strategy in the 1960s against nationalist movements in the country’s former African colonies of Angola, Guinea Bissau and Mozambique.

When most other African countries had liberated themselves from Europe’s colonial yoke, Portugal, one of the earliest colonisers and the poor man of Europe, insisted on retaining its empire. Drawing on research for my upcoming book “Powerful Frequencies: Radio, State, and the Cold War in Angola, 1931-2002”, this article looks at the relationship between military radio propaganda of counterinsurgency to draw some lessons for today’s wars.

Counterinsurgency has garnered renewed attention in the wake of ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Invading Western powers desperately need the cooperation of local populations to fight Iraqi guerrilla insurgents resisting US occupation and Afghani Taliban (along with a congeries of tribal allies and opium traders).

Western military brass and policy wonks repeatedly appeal to the historical, anti-colonial struggles and the counterinsurgency strategies European and US imperialists deployed against local populations as relevant case studies for contemporary wars. Recall, for example, that the Pentagon screened Gillo Pontecorvo’s “The Battle of Algiers” in 2003 to raise the issues of infiltration, interrogation and torture of insurrectionary forces in Iraq.

At the core of all these strategies, old and new, is the blurring of civilian and military practices. Put differently, under these circumstances development is just another word for counterinsurgency. Reform (for civilians) and repression (for rebels), the twin prongs of this strategy, are more intertwined than they are parallel tines.

Bromides about the future are aimed at dulling the violence of forced removals, spying on one’s neighbours and family, and the militarisation of everyday life. Indeed the vaunted progress – roads constructed, homes built, fields tilled – are built on and through big and small acts of violence. The US Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual, (2006), the first to be published in 20 years, offers a tidy dyad in its foreword:

Soldiers and marines are expected to be nation builders as well as warriors.

Anti-colonial radio and the state

In late colonial Angola, radio (the object and the institution), blared the contradictions of this kind of counterinsurgency programme and sounded out the fragmented nature of the colonial state.

One plank of counterinsurgency was what the Portuguese military referred to as “psychological action”. Crafted in the information trenches, psychological action had three targets:

- Civilians – win their hearts and minds;

- Rebel combatants – demoralise them and encourage desertion; and

- Colonial soldiers – maintain their morale and loyalty.

Plainly put, this was propaganda. Both sides used it. The Portuguese almost always played catch up. Military reports from a Counterinsurgency Commission held in 1968-1969 point to the effective histories and radio broadcasts of guerrilla movements. They refer in particular to the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) based in Brazzaville and the need to counteract their transmissions.

The MPLA had been broadcasting guerrilla radio from the mid-1960s via the state radios of the Congo Republic in Brazzaville. Brazzaville, once the site of Charles DeGaulle’s Free French government-in-exile during the Second World War, had the largest transmitter on the continent. The National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA) did much less from their Kinshasa base in Zaire.

MPLA cadres received some training in Algeria. This, with their already Marxist and anti-colonial orientation, meant the programming on Angola Combatente (Fighting Angola) broadcast critiques of colonial occupation and its capitalist ends. It also sent secret messages to movement militants working clandestinely and appealed to Portuguese soldiers to desert.

The FNLA’s Voz Livre de Angola (The Free Voice of Angola) served primarily as a community station for the many African exiles from Angola in the area. The Portuguese secret police (PIDE) faithfully listened and transcribed. Only later, after the Counterinsurgency Commission, did the military develop its own radio propaganda.

The colonial state played a reactive game. They employed various media: radio, newspapers, pamphlets and posters. In Mozambique for example, loudspeakers mounted in aeroplanes as part of Operation Gordian Knot, was the largest and most successful Portuguese counterinsurgency effort. It was based on US counterinsurgency in Vietnam.

The Military Information Secretariat produced news that local papers printed. It was also relayed on civilian radio stations and was loosely coordinated through the official Angolan broadcaster, the EOA or Emissora Oficial de Angola.

Broadcasting in Angola - the longer view

A vast network of radio broadcasters, largely member based radio clubs, developed in Angola from the 1930s. By the 1950s each region of Angola had a least one radio club. This meant a total of 10 broadcasters for a white settler population that reached nearly half a million by the early 1970s. They were also served by a commercial station, another belonging to the diamond mining company Diamang, and the EOA.

Member based groups drew from radio enthusiasts, the local business elite, and, increasingly, young folks. Every club was different in structure and size. While they broadcast in Portuguese, their main focus was local events: football games, car races and radio plays. Many also organised live musical events.

They often implored the colonial state for financial support and strategically lauded Portuguese Prime Minister António Salazar and the work of empire. Yet, radio club broadcasters were largely (though not entirely) deaf to the nationalist cause. Still, these young men and women created a dynamic network and vibrant modernity. If clubs found their broadcasters pressed into broadcasting counterinsurgency messages, it seemed a small price to pay.

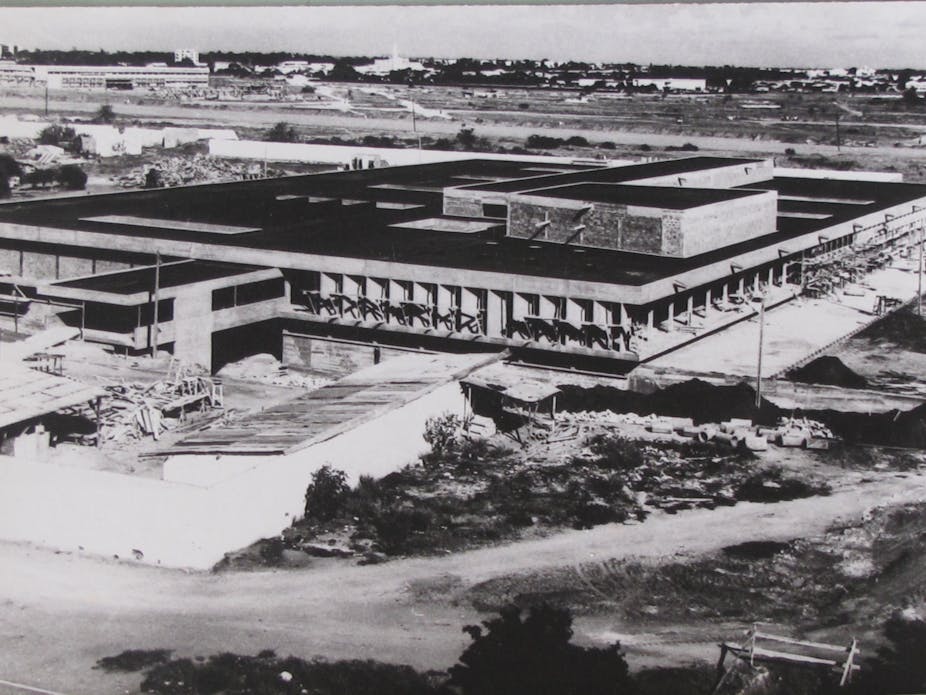

The official EOA opened in the early 1950s (then too a settler initiative). But the war made it more of a priority. The Plan for Radio Broadcasting in Angola, established in 1961 a few short months after the war erupted, attempted to fortify broadcasting structures. The plan was a long term, shifting set of goals. It was grounded in infrastructure and targeted at increasing the state’s broadcasting range.

It put broadcasting in the hands of the Centre for Information and Tourism and the Post Office. But archival files show a jumble of voices and interests. Broadcasters, military and secret police varied in their ideas about how and what radio should do.

We’re jamming

Despite the largely discredited practice of jamming, some military and police figures continued to advocate it well into the late 1960s. Blocking the signal of the guerrilla radios was inefficient and expensive.

But broadcasters from the national broadcaster – Emissora Nacional – in Lisbon, rich in expertise but poor in structural authority, argued for propaganda produced by an autonomous body, not the EOA. Propaganda required nimble structures, free of the state’s imprimatur and staid sound.

In the end, broadcasting policy came down on the side of technological solutions to political problems. Even as the military and secret police argued for responsive forms of counterinsurgency, state policy around broadcasting opted for concrete solutions.

Fast forward to today

The lesson for today is the obvious one. But the one still not learned. No matter how slick the Field Manuals sound and how well they shill the idea that occupying militaries can purvey both violence and the building of a state, the contradictions and complications ultimately undo the best of intentions. You cannot introduce development surrounded by concertina wire or democracy with drones buzzing overhead. And neither will technology fix political problems, which are essentially human.