Queensland’s land clearing has yet again become a national issue. After laws were relaxed under the then Liberal-National state government in 2013, land-clearing rates tripled, undermining efforts to conserve wildlife and reduce carbon emissions.

Now the Labor state government wants to re-tighten the laws. The revised legislation is expected to be debated after June 30.

Land clearing is a highly contentious and polarising issue in Queensland. Scientists and environmental groups have voiced concerns about the dramatic increase in land clearing. But some rural landholders are reportedly worried about the prospect of re-tightened regulations and their possible impact on property values and business certainty.

So, what does the big picture suggest?

Then and now

Since the 1980s, all Australian states and territories have introduced laws to protect native vegetation, in response to rising public concern about land degradation, salinity, biodiversity loss and greenhouse gas emissions.

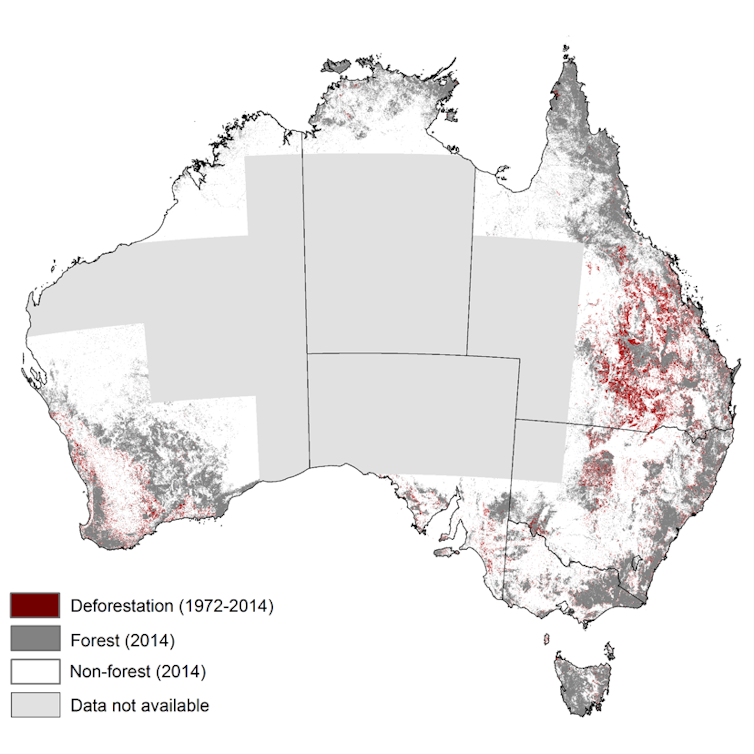

The most significant policy reforms have been in Queensland – where the vast majority of land clearing in Australia has occurred over the past four decades – as I show in a new paper published in Pacific Conservation Biology.

Changes to land-clearing laws in 2007 were heralded as the end of broad-scale clearing in Queensland. Clearing of remnant (old-growth) forest was restricted on freehold land, all remaining clearing permits (issued under a ballot) expired and A$150 million of compensation was provided to landholders. Further amendments in 2009 placed protections on “high value” (more than 20 years old) regrowth forest.

Fast forward to 2012, and Premier Campbell Newman was elected on a promise to keep Queensland’s land clearing laws in place. Soon afterwards though, Natural Resources Minister Andrew Cripps announced the Government would “take an axe” to tree-clearing laws.*

The 2013 amendments:

removed protections on “high value” regrowth forest

allowed landholders to self-assess clearing for activities such as fodder harvesting and vegetation thinning

allowed clearing of remnant forest for “high-value agriculture”

changed the onus of proof so that the Queensland government had to prove that land-clearing laws had been violated.

Queensland’s current Labor government intends to reverse most of the 2013 amendments to vegetation-clearing laws, as well as extending protections on regrowth forest to three additional catchments, to reduce runoff onto the Great Barrier Reef.

The laws will also be retrospective, in an effort to prevent panic clearing before the changes come in.

How does Queensland compare?

Queensland is not alone in its recent changes to vegetation protection laws.

New South Wales introduced self-assessment for “low risk” clearing in 2013. It also promised to repeal the Native Vegetation Act and replace it with a new Biodiversity Conservation Act. An independent review recommended that these changes occur, but environmental groups remain opposed.

Victoria’s vegetation laws were also changed in 2013. The then Coalition government’s changes included the removal of the “net gain” target in vegetation extent and quality that had been in place since 2003. The Victorian Labor government is now undertaking another review of the state’s regulations.

Laws have also been relaxed in Western Australia, where landholders may now clear up to 5 hectares per year on individual properties without a permit (an increase from 1 ha per year).

From state to self-regulation

Within ten years of what looked like the end of broad-scale land clearing in Australia, most state vegetation laws across the country have been relaxed.

Government regulation of native vegetation is generally unpopular with landholders and so maintaining these policies has proven to be politically unpalatable. At this stage, only Queensland is looking to re-strengthen land-clearing laws – and, even so, self-assessment for some clearing activities will remain.

What does this all mean for native vegetation in Australia? This is actually a difficult question to answer.

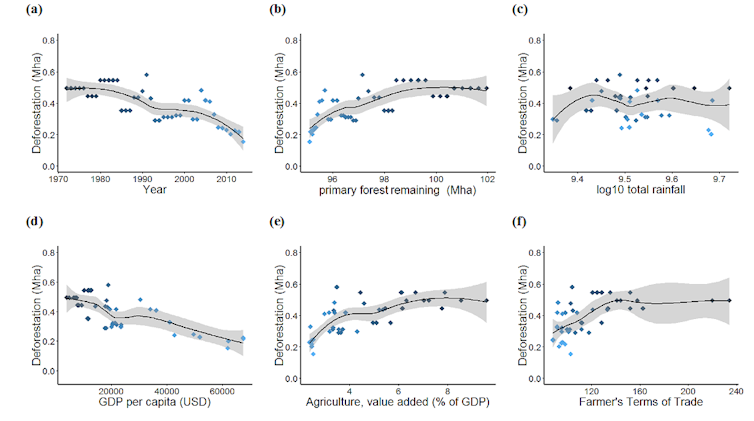

Many factors influence land clearing: rainfall, the price of key agricultural commodities and the amount of land available to clear. This complexity means it’s difficult to know what impact (if any) changes in policy have on the rate of land clearing.

It’s quite clear that the relaxation of Queensland’s clearing laws was followed by a sharp increase in vegetation clearing, but it’s not yet apparent whether this has happened in other states.

A big issue is a lack of reliable data. There’s no consistent reporting of vegetation clearing across Australia. Some states, such as New South Wales, only publish information on the amount of clearing permitted by regulation.

As reported last week, total vegetation clearing in New South Wale is much higher than official data shows as most clearing is exempt from regulation, or illegal.

Better policy needed

If we’re serious about protecting Australia’s native vegetation for the sake of soil health, biodiversity and the climate, we need to use all the tools we have available to achieve this goal.

Using a mixture of government regulation, self-regulation and genuine economic incentives, such as carbon farming, is the best approach.

But no matter which policies we use, they all need to be monitored and evaluated to be effective. Otherwise, we have no idea whether all the time and money devoted to designing and implementing new policies has been worthwhile.

The inconsistency between the federal government’s Direct Action policy and the relaxation of state restrictions on vegetation clearing is a big problem. Landholders need a clear and consistent message from all levels of government if they are to adapt and make long-term business decisions.

Interestingly, around 75% of the recent clearing in Queensland has occurred in the Brigalow Belt and Mulga – areas where we’ve found that carbon farming could be more profitable than cattle grazing.

If only the price, and the policies, were right.

*This sentence was amended on May 10 2016 to clarify that land clearing laws were originally to be maintained.