Between March and April I spent five weeks in New York City, researching ways museums are encouraging visitors to engage with their collections through the use of digital technology. This column reports my experience with Cooper Hewitt’s Pen – an interactive device for exploring the museum’s collection and exhibitions.

Housed in the Andrew Carnegie Mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York City, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum is the only museum in the United States dedicated exclusively to design. The collections include more than 217,000 design objects spanning the “thirty centuries of human creativity”.

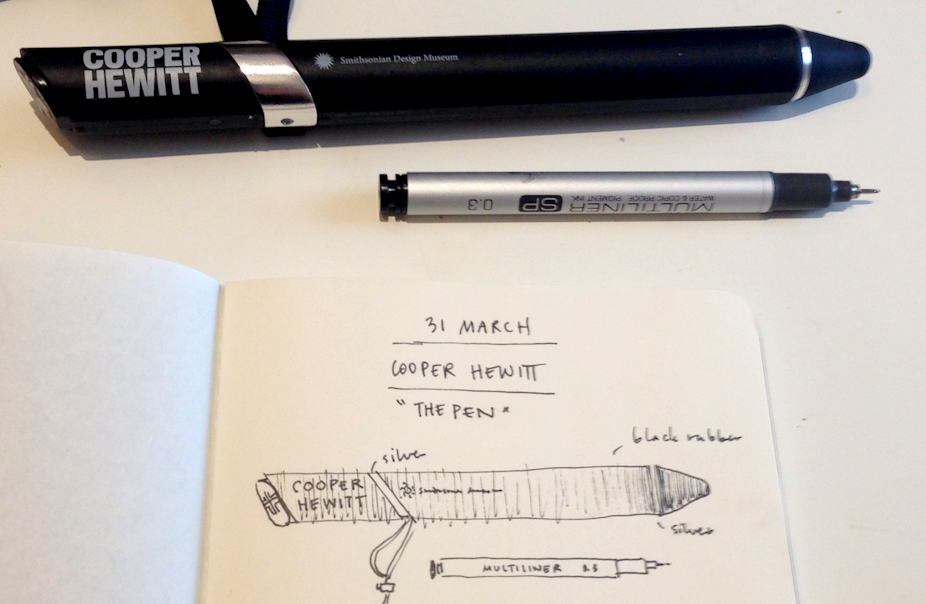

The museum reopened on December 12 2014 after a three-year, US$91 million renovation to develop “immersive museum spaces and participatory visitor experiences never before seen in the museum realm.” One of the most anticipated digital additions to the museum is “the pen”:

A high-tech device that resembles the most basic tool of design, the Pen is a key part of the new Cooper Hewitt experience. Given at admission, it enables every visitor to collect objects from around the galleries and create their own designs on interactive tables. At the end of a visit the Pen is returned and all the objects collected or designed by the visitor are accessible online through a unique web address printed on every ticket. These can be shared online and stored for later use in subsequent visits.

The pen was designed as a more immersive option than existing museum apps. In the past few years museums, libraries and galleries have introduced sophisticated apps that can be used both onsite and online. MoMA’s iPhone app, MONA’s The O and the Curio App at the State Library of NSW provide written, audio and visual content relating to museum collections and specific exhibitions.

Onsite, these apps function as mobile catalogues for visitors to carry through exhibitions. Online, visitors access this same written and audio-visual content, supplemented by longer texts or things “saved” during onsite visits.

The best of the new museum apps are responsive, in that they sense which objects you are standing near and provide customised information to save you time searching or browsing through the catalogue. But apps encourage people to stare at a small digital screen rather than engaging with actual objects and the designed exhibition space.

Cooper Hewitt’s Pen is designed to be more interactive for visitors by allowing users to draw and play on the spot – keeping people engaged in the physical museum environment.

The following account is from my first visit to Cooper Hewitt, intended to provide a new user’s experience of the technology.

When we buy tickets we are each handed a Pen and given a long explanation of how it works. In a nutshell, use the pointy end to tap and draw on the large interactive screens throughout the museum, use the back end to press against the + symbol next to objects to save information (photos and descriptions) which can be accessed later via the museum’s website.

A large interactive table beside the ticket counter (pictured above) encourages us to get used to the Pen as soon as we enter. Staff hover nearby. Like good instructors, they allow people to figure it out by trial and error but assist visitors who are obviously struggling.

Even though it is intuitive, it takes a few moments to get the hang of. You need to be in the mood for play and experimentation, but one hopes visitors to a design museum are.

The “nib” part of the Pen is squishier than I expected. It’s made of soft rubber and requires firm pressure on the screens. My hands are the size of an average eight-year-old’s, so it feels like an oversized novelty pencil. But you’re not writing so much as tapping, swiping and basic sketching.

I find sketching awkward, the accuracy is like drawing in the sand with your finger. I’m reminded of a story about South Korean commuters using sausages as a “meat stylus” when their hands were too cold to go without gloves. Once I get over the clumsiness, the practicality of the device is worth it.

Aside from doing a quick sketch of the Pen itself while having a coffee, I don’t take any notes or sketch in my journal while wandering through the museum. This is unusual for me, but carrying the Pen discourages me from doing so.

Half way through my visit I become slightly anxious. What if my pen doesn’t work? What if I lose my ticket and can’t access all the saved data later (there’s a code on your entrance ticket that allows you to access the data from the website)?

I find myself “saving” things excitedly at first, but more sparingly the longer I’m there. That’s partly because I am engaged by what I’m looking at, but I also start to wonder what am I going to do with all the saved content later.

I wouldn’t necessarily “do something” with my notes and sketches in a journal either, but the act of sketching/ notetaking is a way of engaging with objects and ideas in a museum and committing them to memory. Through sketching, I slow down to observe and think about things. In contrast, quickly pressing the Pen against the wall to “save” content means I tend to read the descriptive information less carefully – I can come back to it later. But I probably won’t.

Many of the exhibits appeal to me due to playful curation. Seeing prehistoric stone tools inhabiting a cabinet with an iPhone – both tools designed to fit comfortably in the palm – is surprising and thought-provoking. A collection of red objects starts to tell me unexpected stories, the juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated things is delightful. I wonder, at the time, if my Pen will capture the curatorial quirks of my experience at the museum.

Back home, when I log-in to the website using the code on the back of my ticket (which I didn’t lose because I put it into my sketch journal) I see that I “collected” 66 items (by touching the back end of the pen to the object label in the museum) and “created” four (things that I drew on the touch screen tables or interacted with and saved).

These objects are saved individually, not curated the way they were presented onsite. I’m glad I snapped a few iPhone photographs of the red collection but wish I had captured others as well.

There’s one object in particular I want to see again, the Hansen Writing Ball. It’s an early version of a typewriter that I became mildly obsessed with a few years ago:

Above left is the iPhone pic I snapped. Right is the image taken from the Cooper Hewitt site. But not from my recorded visit. I collected 66 item which fill two pages (screens) on the website, but no matter how many times I refresh or re-log in, I can’t access the second page items.

Where the Hansen Writing Ball is. I find an image of it by searching the website, but it took ages because I incorrectly remembered it as ‘Hanson’ and it didn’t come up in a search for “typewriter”.

I see that there are two images of the Writing Ball listed on the site – this is also good news. It is a complex machine and if I was sketching I would have drawn it from several angles. If I was documenting properly (even with an iPhone) I would have taken several photographs from different angles. I click on the link and get the message: “the object has been digitised but we can’t show it to you yet.”

The problem with slick technology is that when it doesn’t work exactly as promised, we are easily frustrated. I find myself disappointed that I don’t have access to the items I collect instantaneously, but perhaps it’s better for my long-term brain development that I had to work to find what I wanted, or engage my memory and imagination to think of the object in 3D rather than relying on a series of sketches or photographs.

Ultimately, using the Pen meant I was more engaged in the museum itself than I have been using other phone-based museum apps. And other than researchers or enthusiastic kids, I wonder how many visitors will go back to the objects they collected during their visit anyway?