The Reuters Hot List of “the world’s top climate scientists” is causing a buzz in the climate change community. Reuters ranked these 1,000 scientists based on three criteria: the number of papers published on climate change topics; citations, relative to other papers in the same field; and references by the non-peer reviewed press (for example on social media). The list does not claim that they are the “best” scientists in the world. But the ranking enhances position and reputation, influencing the production, reproduction and dissemination of knowledge.

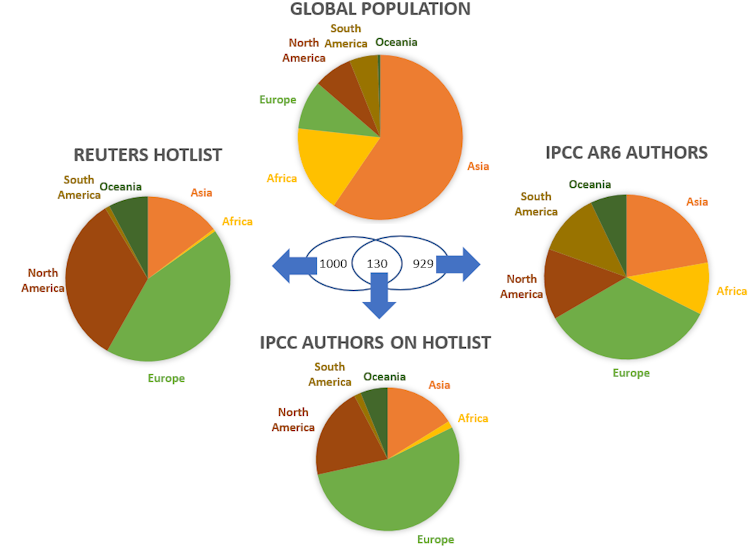

What matters to us, as global South researchers and practitioners working in the field of climate change, is that the geography of this “global” list reveals a striking imbalance. While over three quarters of the global population live in Asia and Africa, over three quarters of the scientists on the list are located in Europe and North America. Only five are listed for Africa.

The list includes 130 of the 929 authors who are contributing to the current reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, arguably the most influential source for climate change policy. Again, the imbalance is stark: 377 (41%) of panel authors are citizens of developing countries (95 from Africa) and only 16 of these are on the Reuters list (only two from Africa).

Climate change science dominated by knowledge produced in the global North cannot address the particular challenges faced by those living in the global South. It also misses significant lessons emerging from the global South, for example from the intersection of climate change with poverty, inequality and informality.

Reuters maps the 1,000 scientists, making it clear that their location is important, yet it does not reflect on what this portrays. While the list is presented as a neutral, data-driven assessment of the top climate scientists, it is silent on the questions of power, authority and inequality this map raises. Where are the global South scientists, and why are they not featuring in this analysis of influence?

We believe that this inequality in influence is a result of unequal access to knowledge production essentials and processes. It also reflects the unequal valuing of climate change scientists’ research focus, which for scientists in the global South is often context-specific, to improve human outcomes and achieve localised return on investment in knowledge.

The list elevates research that contributes to well-established bodies of knowledge on the processes of climate change, and its global and local impacts, much of which has been produced in the global North. Research questions developed in and framed by the global North, for instance questions about environmental perceptions and values, often have limited application or meaning in the global South.

Science from global South matters

The science that is elevated by the list is not the only science that matters. Research from the global South tends to focus on solving challenges on the ground, drawing on multiple voices in local spaces and including practitioner knowledge, to co-produce solutions.

From our experience in Durban on South Africa’s east coast, local researchers, drawing on contextualised and decolonised global knowledge, influence the position of local policy makers and practitioners on climate change solutions. An example is research undertaken in informal settlements by university researchers with communities, which is shaping Durban’s climate change action.

To achieve a better global balance of important work on climate change, a list like the Reuters one could include a measure of the localised application and influence of research. What also matters is that the exclusion of ideas inhibits the production of knowledge for globally relevant innovation, transformation and action. Northern literature dominates global thinking and practice as shown through the spatiality of the list, but this science does not always provide globally relevant solutions, and often has limited application or meaning in the global South.

Read more: Global South scholars are missing from European and US journals. What can be done about it

Addressing the global problem of climate change requires an engagement with the theories, knowledge and experiences from all parts of the world. Science from the global South may well provide innovative climate change solutions, but very little of this science makes it into the global conversation. The imbalance in influence, therefore, has implications for both global and local action.

Global South vulnerable to worst impacts of climate change

The global South is faced with the most severe consequences of climate change. Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and small island developing states are identified as key vulnerability hotpots. Sub-Saharan Africa already has a large share of the population living in multidimensional poverty. Across the continent there is a high dependence on agriculture which is predominantly rain-fed. Changing rainfall patterns and low irrigation rates are compromising these livelihoods. Rapidly growing coastal population centres are increasingly exposed and vulnerable to rising sea levels.

Global literature should support global fight against climate change

Much of the global literature is blind to and silent on the lived experiences of the majority of the globe. This includes extreme and multidimensional poverty, inequality, informality, gender inequity, cultural and language diversity, rapid urbanisation and weak governance, and how these intersect with climate change. An incomplete literature will miss important solutions in the global fight against climate change.

The most compelling story in the Hot List publication is the unequal global distribution of knowledge and expertise. But this is not acknowledged, debated or highlighted as a cause for grave concern. It may not be the responsibility of an international news agency like Reuters to solve this issue, but an agency that claims to provide “trusted intelligence” and “freedom from bias” should at least point it out.