Considering his accomplishments, it’s a surprise that Robert Hooke isn’t more renowned. As a physician, I especially esteem him as the person who identified biology’s most essential unit, the cell.

Like Leonardo da Vinci, Hooke excelled in an incredible array of fields. The remarkable range of his achievements throughout the 1600s encompassed pneumatics, microscopy, mechanics, astronomy and even civil engineering and architecture. Yet this “English Leonardo” – well-known in his time – slipped into relative obscurity for several centuries.

His life and times

Hooke’s life is a rags-to-riches tale. Born in 1635, he was educated at home by his clergyman father. Orphaned at 13 with a meager inheritance, Hooke’s artistic talents landed him scholarships to Westminster School and later Oxford University. There he formed relationships with a variety of important people, most notably Robert Boyle. Hooke became the laboratory assistant of this great chemist – the formulator of Boyle’s law, which describes the inverse relation between the pressure and volume of gases.

Unlike his associates, Hooke was not a man of independent means, and he soon took a paying position as “curator of experiments” at the newly formed Royal Society, making him England’s first salaried scientific researcher. Hooke soon became a fellow of the Royal Society and was appointed to a professorship at Gresham College.

Never marrying, he dwelt the rest of his life in rooms near the Royal Society’s meeting place. This placed him at the epicenter of one of the most important epochs in the history of science, epitomized by the publication of Isaac Newton’s “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy.”

Experiments and innovations

For millennia before Hooke, people had regarded air, along with fire, water and earth, as one of the four elemental substances that filled the world, leaving no empty spaces. Working with Boyle, Hooke developed a vacuum pump that could empty space. In a vessel so evacuated, a candle couldn’t burn, and a clapping bell was silent, proving that air is necessary for combustion and conducting sound.

Moreover, Hooke showed that air could be expanded and compressed. He also performed foundational experiments on the relationship between air and the process of respiration in living organisms. And he laid the groundwork for thermodynamics, by suggesting that particles in matter move faster as they heat up.

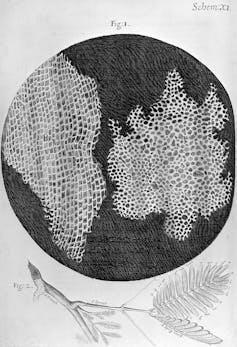

Hooke’s most famous work is his beautifully illustrated “Micrographia,” published in 1665. The microscope had been invented 30 years before his birth. Hooke vaulted the technology forward, using an oil lamp as a light source and a water lens to focus its beams in order to enhance visualization.

He showed that the realm of the very small is as rich and complex and the one that meets the naked eye. Inspecting the structure of cork through his instrument, he named the units he saw cells, after the rooms of monks. Biologists now know that a human body contains approximately 40 trillion of them. From his microscope work, Hooke also developed a wave theory of light.

Hooke pondered some of the biggest biological questions as well. He hypothesized that the presence of fossilized fish in mountainous areas meant they had once been under water. His study of fossils led him to conclude that the Earth has been inhabited by many extinct species.

Hooke’s experiments with mechanical springs led to the formulation of Hooke’s Law, which states that the tension or compression of a spring is proportional to the force applied to it. Physicists now know that this law applies not only to springs but also to a variety of solid elastic bodies, such as manometers, which are used to measure pressure.

These same investigations also enabled him to invent the spring-powered balance watch, which would become a favorite means of keeping time for centuries. Hooke foresaw that with a precise timepiece, oceangoing sailors could find their longitude.

As an astronomer, Hooke suggested that the planet Jupiter rotates, described the center of gravity of the Earth and Moon, illustrated lunar craters and speculated on their origin, discovered a double star and illustrated the Pleiades star cluster.

At a more theoretical level, Hooke also described gravity as the force that pulls celestial bodies together, relating in a 1679 letter to Newton a version of the inverse-square law of gravitational force. When seven years later Newton published his great work “Mathematical Principles,” Hooke concluded incorrectly that Newton – who had already been at work on it at the time of their correspondence – had slighted him.

Contributions to his city

The great fire of London in 1666 presented another opportunity for Hooke to shine. Unlike many contemporaries, he refused to profit dishonestly in the aftermath of the disaster by taking bribes as people worked to rebuild. As surveyor of the city, he collaborated with the renowned architect Christopher Wren to create a monument to the fire.

He also designed a number of great buildings, including Bethlem Hospital (known as Bedlam), the Royal Greenwich Observatory and the Royal College of Physicians. It was in large part through his architectural work that Hooke made his fortune, though he never veered from the frugal habits he developed early in life. Hooke even proposed recreating London’s streets on a grid pattern. Though unsuccessful, his idea was subsequently incorporated in cities such as Liverpool and Washington, D.C.

Surveying the range and depth of Hooke’s contributions, it’s difficult to believe that one person could have accomplished so much in 67 years. Unfortunately, his sometimes rancorous disputes with the likes of Newton over scientific priority contributed to his comparative neglect by science historians, and today we lack any contemporary likeness of him. His birthday is a good time to give him his due as one of the world’s all-time great instrument makers, experimentalists and polymaths.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]