Rock inscriptions made by crews from two North American whaleships in the early 19th century were found superimposed over earlier Aboriginal engravings in the Dampier Archipelago.

Details of the find in northern Western Australia are in a paper published today in Antiquity.

They provide the earliest evidence for North American whalers’ memorialising practices in Australia, and have substantial implications for maritime history.

At the time, the Dampier Archipelago (Murujuga) was home to the Yaburara people. The rock art across the archipelago is testament to their artists asserting their connections to this place for millennia.

Read more: Where art meets industry: protecting the spectacular rock art of the Burrup Peninsula

So did the whalers encounter the Yaburara? Did they engrave over earlier Aboriginal markings as an act of assertion, a realignment of a shifting political landscape? Or were they simply marking a milestone in their multi-year voyages, celebrating landfall after many months at sea?

The answer to all these questions is, we don’t know.

But these inscriptions provide a rare insight into the lives of whalers, filling a gap in our knowledge about this earliest industry on our northwestern coast.

Such historical inscriptions might be dismissed as graffiti. However, like other rock art, they tell important stories about our human past that cannot be gleaned from other sources.

Whaling in Australia

Ship-based whaling was a global phenomenon that lasted centuries. At its peak in the mid-19th century, around 900 wooden sailing ships were at sea on multi-year voyages, crewed by around 22,000 whalemen.

Most whaling in Australian waters was conducted by foreign vessels, and in the 19th century North American whalers dominated the globe.

Whaling led to some of the earliest contacts between American, European and a range of indigenous societies in Africa, Australasia and the Pacific.

But early visits by foreign whalers to Australia’s northwest are poorly documented given the absence of a British colonial land-based presence in the area until the 1860s.

While explorer William Dampier named the Dampier Archipelago and Rosemary Island in 1699, British naval Captain Phillip Parker King was the first to document encounters with the Yaburara people in 1818. His visit to the archipelago in the rainy season (February) coincided with large groups of people using the seasonally abundant resources at this time.

The Swan River Colony (Perth) was established in 1829, but permanent European colonisation of the northwest only began in the early 1860s with an influx of pastoralists and pearlers.

For the Yaburara, this colonisation was catastrophic. It culminated in the Flying Foam Massacre in 1868 in which many Yaburara people were killed.

Early whaling contact

A few surviving ship logbooks record English and North American whalers on the Dampier Archipelago from 1801, but the heyday of whaling near “The Rosemary Islands” was between the 1840s and 1860s.

The logbooks describe American whaling ships worked together to hunt herds of humpback whales, which migrate along Australia’s northwest coastline during the winter months.

The ships’ crews made landfall to collect firewood and drinking water, and to post lookouts on vantage points to assist in sighting whales for the open boats to pursue.

Research by archaeologists from the University of Western Australia working with the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation and industry partner Rio Tinto has found some evidence of two such landfalls in inscriptions from the crew of two North American whalers – the Connecticut and the Delta.

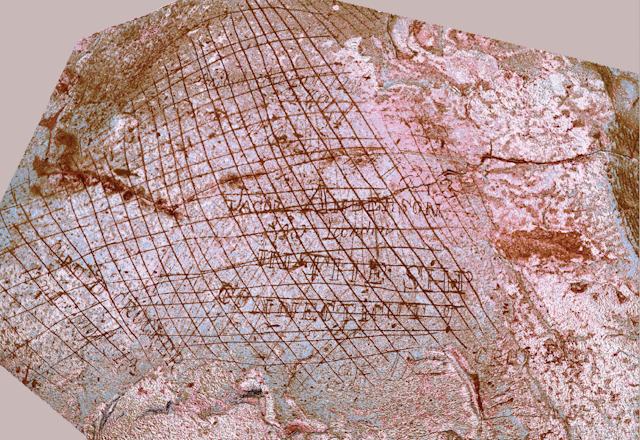

The earliest of these inscriptions records that the Connecticut visited Rosemary Island on August 18 1842. At least part of this inscription was made by Jacob Anderson, identified from the Connecticut’s crew list as a 19-year-old African-American sailor.

Research shows this set of ships’ and people’s names was placed over an earlier set of Aboriginal grid motifs. This was along a ridgeline that has millennia of evidence for the Yaburara producing rock art and raising standing stones and quarrying tool-stone elevated above this seascape.

The dates and names found in the inscription correlate with port records that show the Connecticut left the town of New London in Connecticut, US, for the New Holland ground (as the waters off Australia’s northwest were known) in 1841, with Captain Daniel Crocker and a crew of 26.

The Connecticut returned to New London on June 16 1843, with 1,800 barrels of oil, travelling via Fremantle, New Zealand and Cape Horn.

The Connecticut’s logbook for the voyage is missing, so without these inscriptions we would know nothing of this ship’s visit to the Dampier Archipelago.

On another island, another set of inscriptions record a visit to a similar vantage point by crew of the Delta on July 12 1849.

Registered in Greenport, New York, the Delta made 18 global whaling voyages between 1832 and 1856. Its logbook confirms it was whaling in the Dampier Archipelago between June 2 and September 8 1849.

While the log records crew members going ashore to shoot kangaroos and collect water, no mention is made of them making inscriptions or having any contact with Yaburara people.

Given it was the dry season, and the lack of permanent water on the islands, this lack of contact is not surprising.

But again, these whalers chose to make their marks on surfaces that were already marked by the Yaburara. By recording their presence at these specific historical moments, the whalers continued the long tradition of the Yaburara in interacting with and marking their maritime environment.

Protecting the heritage

Between 1822 and 1963, whalers killed more than 26,000 southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) and 40,000 humpback whales (Megaptera novaengliae) in Australia and New Zealand, driving populations to near-extinction.

Commercial whaling in Australian waters ended 40 years ago on November 21 1978, with the closure of the Cheynes Beach Whaling Station in Albany, Western Australia.

Today there are signs of renewal, with whale populations increasing, and Aboriginal people are reclaiming responsibility for management of the archipelago.

Read more: Explainer: why the rock art of Murujuga deserves World Heritage status

There is a strong push for World Heritage Listing of Murujuga — one of the most significant concentrations for human artistic creativity on the planet, recording millennia of human responses to the sustainable use of this productive landscape.

These two whaling inscriptions provide the only known archaeological insight into this earliest global resource extraction in Australia’s northwest - the whale oil industry - which began over two centuries ago.

They demonstrate yet again the unique capacity of Murujuga’s rock art to shed light on previously unknown details of our shared human history.