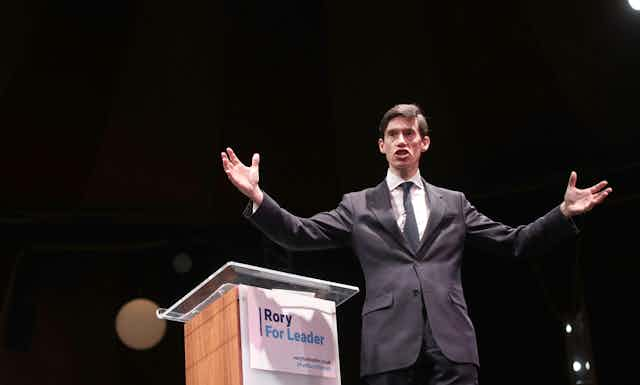

On the basis of the immediate coverage of the first Conservative leadership ballot, there were two winners and eight losers. Boris Johnson grabbed the headlines with his impressive tally of 114 votes, leaving his rivals scrambling. But the other winner was Rory Stewart, the international development secretary and widely seen as an also-ran, who booked his place in the second round of MPs votes. Stewart won 19 votes to finish in seventh place, despite most pundits predicting he would be eliminated. He pronounced himself “absolutely over the moon” and claimed he had momentum.

Stewart’s candidacy has been propelled by an unconventional social media campaign. He toured the country doing short notice meet-and-greets with the public and recording off-beat videos. This, and his his willingness to shoot from the hip to attack Brexiteers, has helped acquire him a cult following. This has not necessarily extended to Conservatives, however. The senior activist, Tim Montgomerie, memorably described Stewart as “the most popular candidate with people who’ll never vote Tory”.

Who is Rory Stewart?

Born in Hong Kong and the son of a diplomat, Stewart pursued his early career in the Foreign Office. After a number of postings, he was appointed a senior official in the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. He later worked for a development NGO in Afghanistan.

In 2010, Stewart was elected as the Conservative MP for Penrith and the Border in Cumbria. He presented a BBC television series on the history of the land around the English-Scottish border and wrote a bestselling book on the area.

In parliament, Stewart joined the government in a junior capacity in 2015 before being appointed to the cabinet in 2019 as secretary of state for international development after a reshuffle caused by Gavin Williamson’s sacking.

His entry into the Conservative leadership contest was unexpected but by the force of his personality, he has managed to make an impression. Although a maverick, Stewart demonstrated a strong loyalty to the prime minister, Theresa May, and her Brexit deal with the EU. He strongly opposes a no-deal Brexit of the type advocated by some Brexiteers.

Indeed, supporters of Johnson have suspected Stewart of being an outrider for Michael Gove – another leadership candidate – whose role was to launch attention-grabbing attacks on Johnson to diminish his support and channel it towards Gove, while the environment secretary maintained his distance. Once eliminated, they anticipated that Stewart would back Gove. This theory has evidently note been borne out in the first round.

An unconventional candidate …

After overachieving in the first ballot, Stewart insists he is in it to win it. His support most likely came entirely from Remainer MPs. He was publicly endorsed by the former chancellor, Kenneth Clarke, as well as by the current cabinet minister, David Gauke. The fact that he won many more votes than public endorsements may have reflected the desire of supportive pro-EU Tory rebels not to damage his standing with the wider party by associating him too closely with their campaign against Brexit.

Stewart’s supporters present him as a straight talker who can connect with ordinary people. But he has a tendency to make outlandish statements, such as his claim in a radio interview that 80% of the public backed May’s Brexit deal. He immediately withdrew the remark and apologised, saying that he was “producing a number” to “illustrate what I believe”. He has had to row back from other comments, including when he indicated he would support Labour’s parliamentary motion against a no-deal Brexit only to reverse his position shortly afterwards.

Such incidents raise questions over his political judgement. This has become particularly apparent in Stewart’s attacks on Johnson. After the first leadership ballot, he vowed to “bring down” Johnson if the latter sought to prorogue parliament and force through a no-deal Brexit. Stewart even threatened to set up a new assembly in Westminster’s Methodist Central Hall if the government suspended parliament.

These comments drive many Conservatives to despair. They worry that Stewart is providing attack lines for opposition parties against the man who is almost certain to be the next prime minister. The fact this is being done by a serving cabinet minister is little short of extraordinary. Stewart previously announced he would not serve in a Johnson cabinet because of disagreements over Brexit. But true to form, he is now indicating that he might after all.

… but still a politician

Neither is Stewart averse to spinning like any other politician. On the day of the first parliamentary ballot, he repeatedly proclaimed that he was second to Johnson in a poll of Conservative grassroots members. As a bald statement, it was true, but he neglected to mention that Johnson was on 54% and Stewart himself on just 11% (next came Raab on 8%, Gove on 8% and Hunt on 7%). Stewart’s second-place ranking was not evidence of a surge of enthusiasm among the membership for his candidacy but an artefact of a divided field in which there was no clear and obvious rival to Johnson. Stewart was – barely – the best of the mediocre rest.

Despite the publicity around his candidacy, Stewart surely has little chance of progressing beyond the next round of parliamentary ballots, let alone reaching the final all-member ballot. It is inconceivable that he could lead the Conservatives at this point in their history. His views on Brexit would split the party and quicken the leakage of votes to Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party. Taken together with concerns over his judgement, the likelihood is that Stewart would struggle to impose his authority.

Nevertheless, Stewart has cemented his position as the breakout performer in the leadership contest. He could play a role in helping his party broaden its appeal among the electorate. But that may have to await the resolution of Brexit. Unless he rediscovers an appetite for loyalty, Stewart could become a thorn in the side of a Johnson government.