Earlier this year, an anonymous “friend” of Marina Picasso – the granddaughter of artist Pablo Picasso – revealed to the New York Post that the heiress was looking to put up a number of her grandfather’s works up for sale. This was confirmed by Ms. Picasso, who seeks to raise funds to increase her philanthropic work.

“It’s better for me to sell my works and preserve the money, to redistribute to humanitarian causes,” she told The New York Times in February. “It is an inheritance without love,” she later revealed.

She said she hadn’t decided how many she was planning to sell, although she’s reportedly accepting offers privately for seven of her grandfather’s works, worth an estimated $307.4 million.

So why are some in the art world so concerned? Why is Marina Picasso selling the artworks now? And how did these works come into her possession in the first place?

A fractured family

As Alan Riding wrote in a 1999 New York Times article about Picasso’s relatives, “children of the rich, famous and powerful rarely have it easy.” But Picasso’s descendants have suffered more than most.

Pablo Picasso’s first marriage took place in 1918 to Olga Khokhlova, a dancer with the Ballet Russe. Although they lived separately, they would remain married until her death in 1955. Their son, Paulo (1921) – whom Picasso routinely ill-treated – was the artist’s only legitimate child.

Paulo had three children of his own: Marina (1951) and Pablito (1954) from his first wife, and Bernard (1959) from his second. In 1971, Paulo died from cirrhosis of the liver.

Pablo Picasso passed away in 1973. The same year, his grandson Pablito (Marina’s brother) died in a hospital after swallowing bleach. Four years later, his former mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter hanged herself, and his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, shot herself in 1986.

Picasso left no written will, and the heirs entered into a bitter dispute over the estate. Valued then at $260 million, it included more than 35,000 paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures and ceramics, in addition to real estate and several homes.

Maurice Rheims, an expert appraiser, spent five years determining their status and cataloging the 1,885 paintings, 7,089 drawings, 3,222 ceramic works, 17,411 prints and 1,723 plates, 1,228 sculptures, 6,121 lithographs, 453 lithographic stones, 11 tapestries and eight rugs.

Divvying it up

Soon after Picasso’s death, the French government amended France’s inheritance tax law to allow Picasso’s heirs to pay the taxes owed by his estate in art instead of money. Ultimately, the French state took 3,800 works, which formed the core of the Musée Picasso. The rest was left for the family to divide.

Although conflicting reports of the distribution have been made, the widow’s share amounted to roughly three-tenths of the art, or $52 million in 1977, after taxes; the three illegitimate children, Maya, Claude and Paloma, were awarded one-tenth, or $18 million worth of art; meanwhile, Marina and Bernard each received one-fifth of the the art, slices valued at $35 million. Additionally, Bernard received the chateau at Boisgeloup in Normandy, while Marina inherited the sumptuous La Californie.

Marina’s share, like Bernard’s, is more representative of Picasso’s career than that of any other heir; the two of them have more early works because of the community property Picasso shared with Olga Khokhlova, their grandmother. When they separated in 1935, Olga had had her lawyer request an inventory of her husband’s property at the time.

The Online Picasso Project, which I direct, currently includes 25,159 items, of which 19,332 are unique artworks (i.e., excluding lithographs, engravings, ceramics and photographs). Of these, 598 artworks are still listed as being part of the Marina Picasso Collection (85 paintings, 490 works on paper and 18 sculptures); and 326 artworks (62 paintings, 264 works on paper and 12 sculptures) are known to have formerly been in her collection. Assuming that the Online Picasso Project has a representative sample of the Marina Picasso collection, this seems to indicate that she has already sold about 35% of her collection.

Marina seems to have little sentimental attachment to her grandfather’s work. “I respect my grandfather and his stature as an artist,” she said last month. “I was his grandchild and his heir. But never the grandchild of his heart.”

A force in the arts market

One of the major issues to resolve upon Picasso’s death was the marketing of his works. “Picasso almost has to be treated as if he were a living artist,” a dealer told The New York Times in 1980. “There is so much stuff that it has to be marketed very carefully over a long period of time. If too much were offered at once, it could cause prices to fall sharply.”

Over the ensuing years, Marina Picasso’s representative, a Geneva-based art dealer named Jan Krugier, staged exhibitions of the Marina Picasso collection and organized two international tours.

In 2006, Krugier exhibited seven paintings, two sculptures and several drawings.

“Prices have gone crazy,” he explained to The Art Newspaper at the time. “I don’t understand it anymore. Because of this, there are masses [of Picassos] coming out at the moment.” Another art dealer, Nick Maclean, was reported in the same article as saying, “It seems there is no satisfying the appetite in today’s market for Picasso’s work.”

This interest has only grown. Over the last nine years, more money has been spent on Picasso than on any other artist. In 2014, according to the New York-based art market database Artnet, auction sales of Picasso’s were second only to Andy Warhol – $449 million last year in a $16 billion international market. Every year, over 1,500 Picasso’s change hands at auctions.

Due to the secrecy of the art market, it’s difficult to determine exactly which artworks still remain with Marina Picasso. However in 2014, the following works of hers were auctioned: Verres et bouteilles (1914), Collage avec feuille, ficelle et tulle (Guitare) (1926), Composition avec femme aux cheveux mi-longs (1930), Portrait de Marie-Thérèse (1932), Femme à la collerette (1941), Femme allongée (1946) and Bouquet (1969).

Together, they’ve netted her between $10.6 million and $15 million – and that’s just from last year.

Will prices plummet?

While other Picasso heirs have occasionally sold works, Marina is the only one who seems to be increasing the number of her grandfather’s works for sale.

It’s not all for personal gain: Ms. Picasso has used the proceeds from her sales and exhibitions for a number of philanthropic endeavors, ranging from the establishing orphanages and offering agriculture subsidies in Vietnam, to funding mental health care causes in Europe.

“For once, I’m doing something with my grandfather, even if he is no longer with us,” she was quoted saying in The Independent last year. “This sale is a way of making him take part in my life’s work.”

The figures attached to the paintings supposedly hitting the market in 2015 are even more exorbitant than 2014’s.

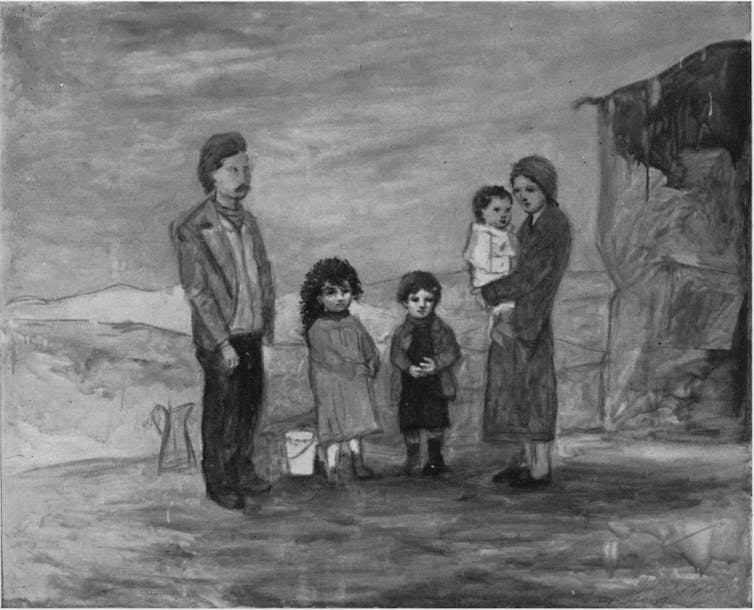

One work that Ms. Picasso will sell in the upcoming batch is the painting La famille (1935), a rare, realistically styled painting that is unusual for Picasso.

Other works purported for sale are Portrait de femme (Olga) (1923), valued at $60 million, Maternité (1921) at $54 million and Femme à la mandoline (Mademoiselle Leonieassise) (1911) at $60 million.

Yet the announcement has art investors, auctioneers and dealers worried. In an interesting twist, Ms. Picasso revealed in an interview with Doreen Carvajal of The New York Times that she would sell works privately and would judge “one by one, based on need,” how many and which of the remaining Picasso works she would put up for sale.

The news of her unusual strategy is spreading in select circles by word of mouth, leading to speculation that she either could flood the market or, without guidance from dealers, sell individual works for less than top dollar. In both cases, prices could depress across the board.

Ultimately, according to Mark Brown, arts correspondent for The Guardian, how much of an impact the sale will truly have on the art market depends on how much of her enormous collection she intends to sell.

It’s more realistic that she’ll be selling one or two pictures a year, “and that is a long way from flooding the market,” he wrote.