The idea of using satellites to monitor wildlife and biological diversity probably conjures up images of radio-collared deer or tagged turtles. And while these have been key to increasing our understanding of animal distribution worldwide, we can track a lot more from space than you’d imagine – and it’s not necessary to capture and fit a tracking device first.

For example, hyperspectral sensors – which capture information across the electromagnetic spectrum in very narrow bands able to detect recognisable “fingerprints” of objects – have been used to determine genetic differences in Populus tremuloides (trembling aspen), one of the most widespread and genetically diverse species in North America. Satellite information on climatic conditions and on vegetation type and dynamics can help predict animal movement and condition. These are just two examples taken from a special edition I co-edited on satellites and conservation in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B journal.

Who is interested in satellite remote sensing? Basically anyone who seeks to understand large scale patterns in biodiversity distribution, or that has to deal with the management of big, remote, or inaccessible areas.

An unparalleled view from above

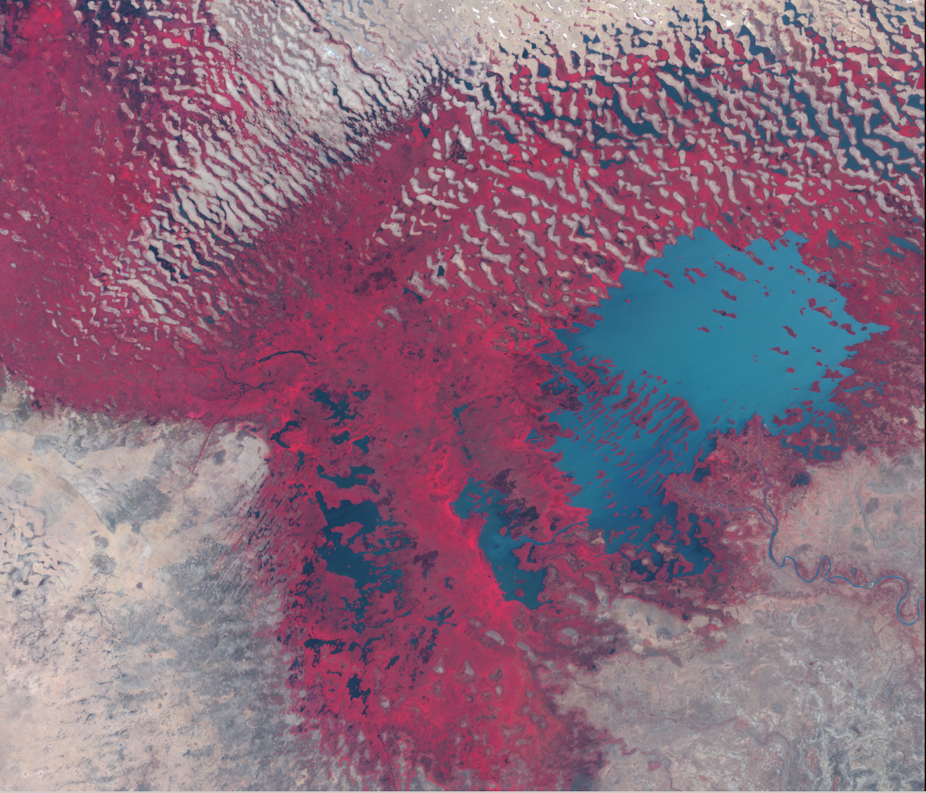

The level of information that can be derived from satellite data is pretty phenomenal, and too-often undervalued by ecologists and conservationists. For example, emperor penguin colonies can be found and the colony size estimated using very high resolution images. Changes to the extent or density of ecosystems can be tracked, and active sensors such as radar and lidar can report the 3D structure and density of vegetation. Just how “green” our world is can be extensively mapped on a fortnightly basis.

So satellites help monitor both wildlife and vegetation in the natural world, able to provide information about the most remote and inaccessible places on Earth. They also capture information that helps us understand why, and predict where, biodiversity is declining.

For example, measurements taken on the ground can be integrated with satellite data to track the current distributions of certain invasive species, and to predict their projected advance. High resolution images can be used to map problems associated with oil exploration and exploitation. The response of animals to shifts in temperatures or availability in food and resources can be analysed and predicted from satellite-based information. And deforestation, land degradation and the fragmentation of ecosystems as well as the expansion of urban areas have all been successfully monitored using satellites’ unique viewpoint.

Satellites’ benefits extend beyond land to the oceans too, as there are some great examples of how satellites can support marine conservation. Spotting and monitoring oil spills is a classic example, using radar or infrared sensors. And using satellite data together with that from vessels’ monitoring systems make it easier to detect illegal, undeclared or unreported fishing.

Key new technologies need to be used

Remote sensing is becoming central to our ability to understand and manage the natural world. From camera traps and microphone arrays, to guided drones and Doppler radar, ecologists, conservationists and environmental or wildlife managers have been drawn towards new technological developments that provide the possibility of non-invasive monitoring.

Satellite sensors are part of this incredibly powerful toolkit, and their scope to inform research and support resource management is continuously growing. For example, satellite data is now used to inform protected area management or species reintroduction programs.

Perhaps obviously, the best uses for this technology and major breakthroughs are most likely to occur when remote sensing and conservation experts collaborate; yet this happens all too rarely. Conservationists and wildlife managers need better links to technical expertise and access to equipment, and working together would be greatly enhanced by common information-sharing platforms and the development of a more coordinated research agenda. Google Earth is one thing, but making government-funded satellite data and the software tools to use it freely accessible would be a key step to increase the number of new purposes the research community can put it to.