It is time for all Australian governments to acknowledge a historic wrong. In doing so they will help to right an injustice and demonstrate a real commitment to respect for all Australians.

Earlier this week, the Victorian government, heeding recommendations by the Human Rights Law Centre (HRLC) and exemplary analysis by legal academic Paula Gerber, announced that it will allow expungement of the criminal records for those convicted of consensual same-sex activities.

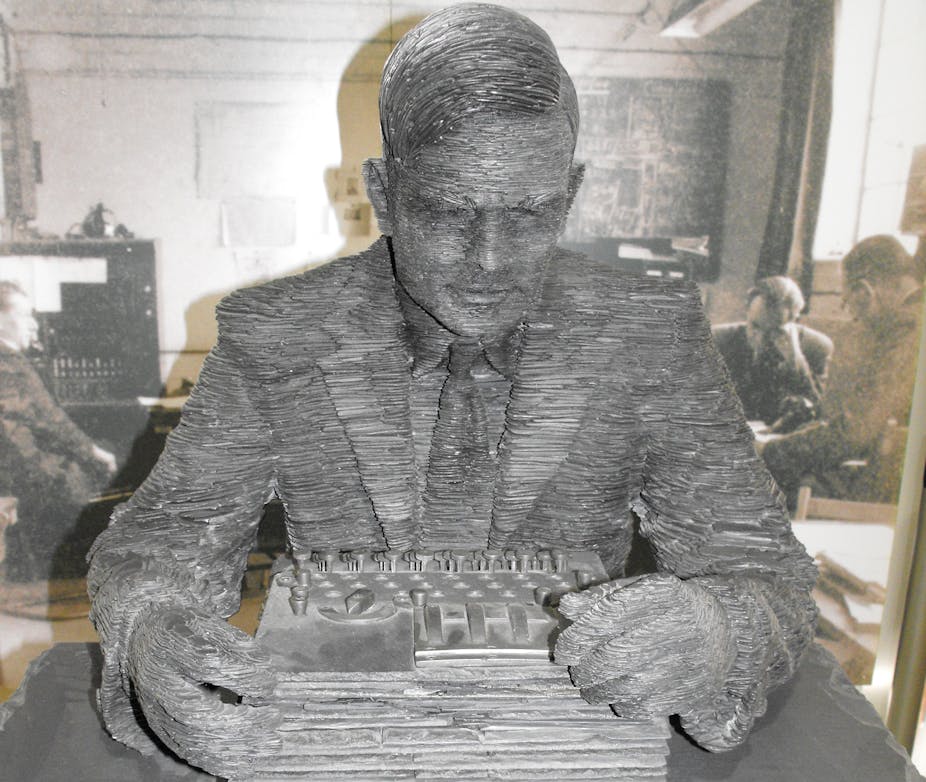

Late last year, the UK government seized a media opportunity and formally pardoned Alan Turing, the genius whose work at Bletchley Park, the location of the UK’s military decryption operation, helped to defeat Hitler in World War Two. Turing was prosecuted for the crime of sleeping with another man, a consenting adult.

Their crime took place in private. There was no coercion, no violence. Turing’s punishment as a result of his 1952 conviction involved a form of chemical castration, restrictions on travel and loss of employment opportunities.

Turing committed suicide. He was accordingly unable to use the UK Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, which allows men to expunge their criminal convictions for same-sex activity. The legislation covers only those men who were still alive.

What does expunging a record mean?

Expungement means that their conviction no longer appears as a criminal record. It doesn’t mean that the conviction was illegal. Nor does it mean that the government will provide compensation to the several thousand men who were sentenced to time in prison or chemical treatment for what numerous Australians do in private every day.

Victoria decriminalised consensual same-sex activity involving adults in 1981. Other jurisdictions took longer. In Tasmania in particular, law reform involved litigation in the High Court and reference to international human rights agreements, resulting in decriminalisation as late as 1997.

All Australian jurisdictions now recognise that governments should stay out of the bedrooms of gay men, lesbian women and their straight peers. There is no reason for intervention in the private sphere unless there is violence, coercion or other harm.

The Victorian commitment is not yet law but should be welcomed as an indication of respect for all people, rather than just those with a same-sex affinity or curiosity. It embodies respect for human dignity: the autonomy that we expect in a liberal democratic state. It also respects privacy as a freedom from inappropriate interference.

Change in Victoria means that people will be able to request that their conviction be removed from the official record. At the moment, the conviction represents a life sentence. People remain on sex offender registers indefinitely, even though the formal punishment was restricted to time in prison or a fine. Inclusion on registers prevents the convicted from working with children and historically has precluded people from areas of employment.

There are no authoritative national figures on the number of people with convictions who are still alive and who will seek expungement. Governments aren’t rushing to provide data and probably don’t know. Expungement is an acknowledgement of a wrong rather than a silver bullet. As with the UK regime, there will be no scope for compensation.

The change does not mean that law in the 1950s or 1970s was invalid. It does not mean that prosecutions were illegal. People will still be held to have been legally convicted; only their records will be cleared.

Expungement will not cover convictions involving minors or violence. That is one reason that the government hasn’t simply cleared all convictions or comprehensively awarded a pardon such as that granted to Turing. It will deal with expungement on a case-by-case basis to reflect bureaucratic convenience and individual circumstances.

The case for saying sorry

It is time for the other Australian state governments to emulate Victoria and adopt the HRLC recommendations. Adoption should feature both scope for expungement and a clear statement of regret by governments about past practice.

Saying sorry doesn’t involve liability or foster litigation. It does signal respect for people whose privacy should have been respected and provide an acknowledgement that the state should keep out of contemporary bedrooms.

Privacy is one of those traditional freedoms that we should expect newly appointed Human Rights Commissioner Tim Wilson to strongly encourage as an aspect of human dignity and liberty. Civil society bodies such as the Australian Privacy Foundation have called on state and territory governments to act without delay.

An acknowledgement of wrong should also come from the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The military traditionally excluded recruits and punished servicemen and women who were perceived or found to have a same-sex affinity. Some of those people were heroic, others not. Some gave their lives for Australia.

Discrimination on the basis of which adult is sharing your doona has no place in Australia in the public or private sectors.

Saying sorry isn’t hard. It’s what we teach our five-year-olds. For Australian authorities to say sorry would send the right signal about diversity, dignity and privacy. It’s what we should expect from premiers, chief ministers, the ADF and other bodies.