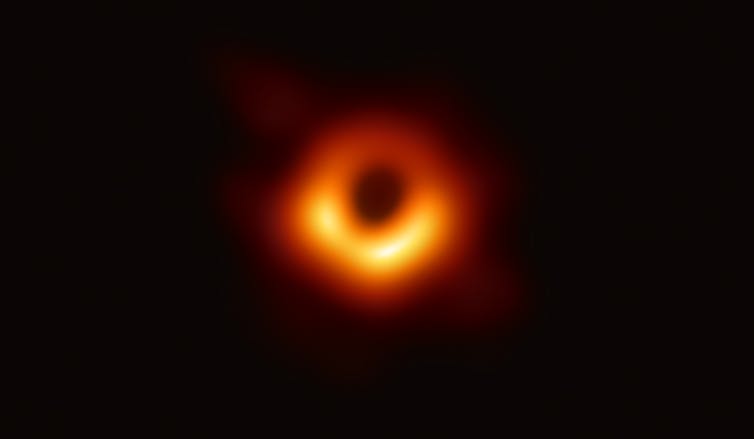

Were you recently gobsmacked when you saw the very first image of a black hole? I know I was.

Did I understand what I was seeing? Not exactly. I certainly needed an explanation, or two. But first and foremost, I stopped to look, as I bet many others did, too … and then, I began to ask questions.

Pictures like this of the universe are amazing and mysterious and spark curiosity. I am convinced that part of the keen interest in all things astronomical has to do with the images scientists share – like the black hole, and so many other Hubble telescope images, for example. Those popular images are welcoming and help make the science accessible.

I contend people are less afraid to ask questions when they see images. Most have taken pictures and can even speak a photographic “language.” You can take notice of color, for example, and wonder if it suggests meaning – why is that black hole orange? I bet you know how to ask questions about a photograph.

For years, as a science photographer, I’ve been trying to persuade my colleagues in research that they can create more compelling images of their work. With simple techniques described in my new book “Picturing Science and Engineering,” scientists, and anyone else for that matter, can easily create a more interesting image — one to engage a viewer to pay attention.

It’s no longer good enough to create photographs or other visuals only for the experts. Learning how to speak to non-experts is essential if scientists are to combat the frightening present atmosphere of scientific mistrust.

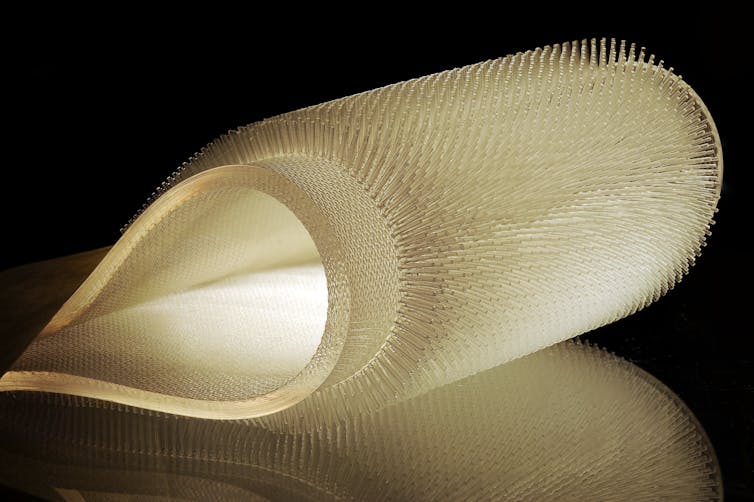

Here, for example, is an image that researcher Alice Nasto created of her work in Mechanical Engineering at MIT. She fabricated material that emulated sea otter fur for the purpose of studying insulation. Compare it with the photograph that I made of the same material. If you don’t see the difference, then I am in real trouble.

I hope you are more compelled to look at the image that I made of the same material. All I did was fold it and light it differently. There was nothing terribly complicated about my process. But because of the drama of the lighting you are more compelled to look. In addition, folding the material gives you more information – it is highly flexible, with a “hairy” surface.

The fact is, science is all around you. Everything you see has to do with various scientific phenomena. Why not start a conversation about what’s going on scientifically by looking at those phenomena in a compelling image?

For example, have you ever noticed the condensation forming on the inside of a glass lid while sauteing colored peppers?

I made this image with my phone, taking advantage of the opportunity phone cameras offer to capture an evanescent moment. I quickly snapped the shot. In just a few seconds that image was gone, as I knew it would be. You are seeing condensation of water as the cooking peppers steam; on the glass cover, it’s easy to see how that phenomenon effects the optics of the colors.

Or take this next image.

While walking along a street in Boston, I realized some of the trees were wrapped in cellophane. I have no idea why. But it grabbed my attention when I noticed that several of the water drops formed a line along a couple of creases.

There’s some interesting physics behind why that happens. The crease is acting as a guide for the water drops. The drops are “self-assembling,” a phenomenon which is key to various nanotechnology fields. One example found in nature is the way DNA is assembled in our cells, guided by a messenger RNA. In laboratories, researchers are assembling drugs by creating substrates that will attract certain chemicals.

Often, concepts or structures in science are not possible to photograph. When that’s the case, I try to come up with some sort of photographic metaphor that suggests the idea. Here’s one example.

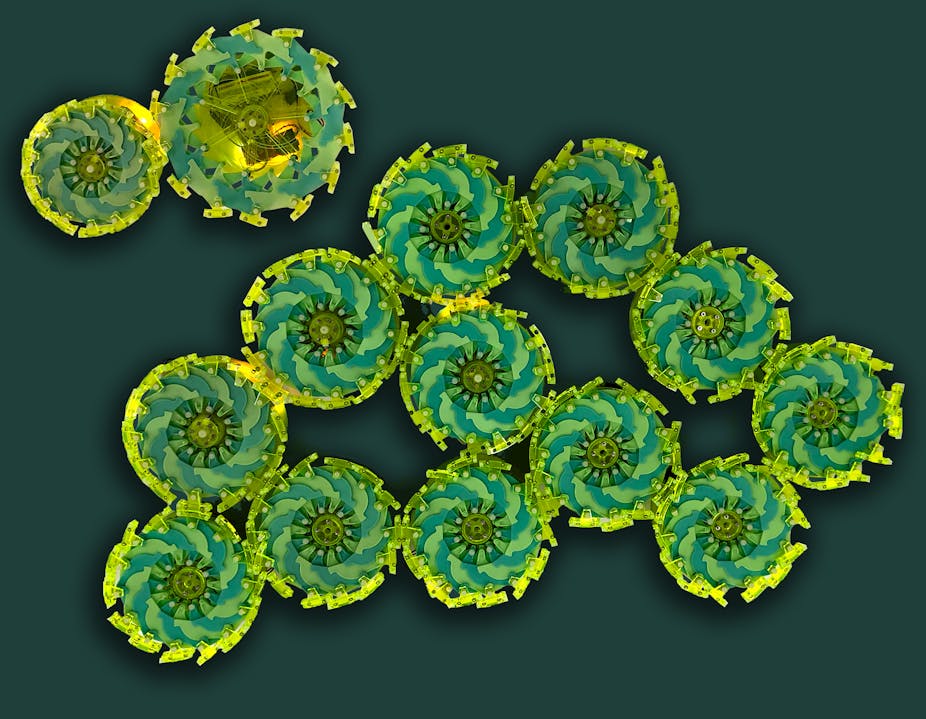

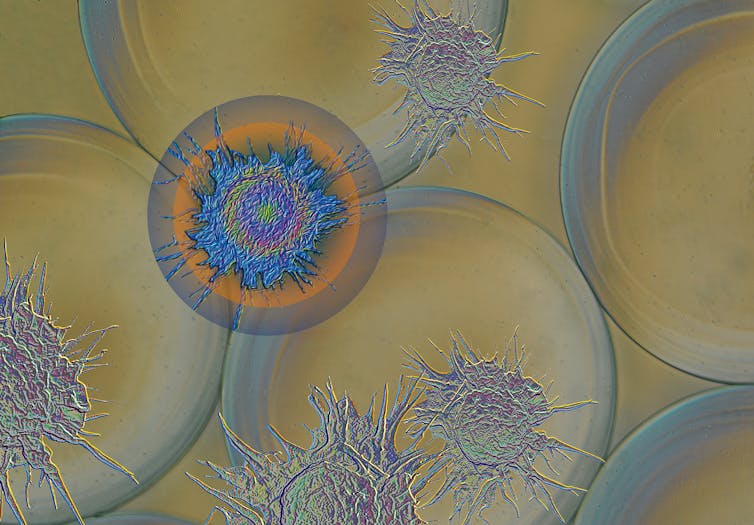

Scientists developed a technique that “deactivated” particular cells in our bodies – macrophages – so that they would not fight against an implanted medical device. As a way to illustrate this research, I combined a few pieces of images that I’d previously made to suggest the idea behind it. The metaphor is not perfect – all metaphors fall apart – but it was good enough to get the cover of an important journal.

In “Ways of Seeing,” art critic John Berger wrote, “We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.”

Choosing to look at science might very well be the first step in having important conversations about the world around you.