Foundation essay: This article on the debate over Scottish independence is part of a series marking the launch of The Conversation in the UK. Our foundation essays are longer than our usual comment and analysis articles and take a wider look at key issues affecting society.

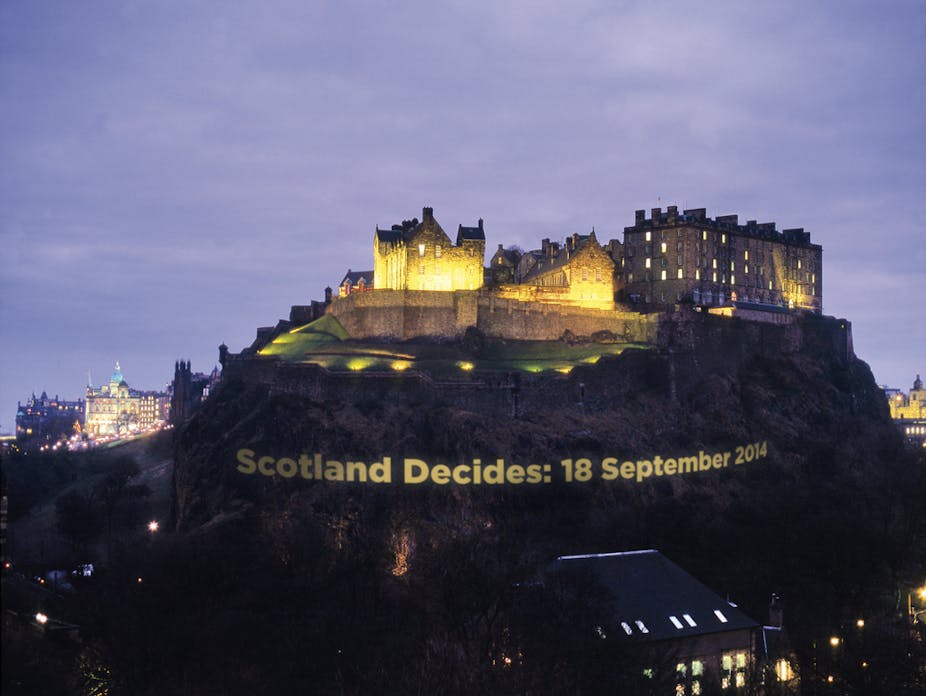

The Edinburgh Agreement of October 2012 pledged both Scottish and UK governments to holding a referendum on Scottish independence before the end of 2014 and to accepting the outcome. A few weeks later, with the help of the Electoral Commission, they agreed on the wording of the question:

Should Scotland should be an independent country? Yes/No

The outcome will be decided by a simple majority of those voting. In an international context, this is remarkable. Nearly 20 years after the last Quebec referendum, Canadians still argue about the wording of any future question, while the very idea of a referendum in Catalonia is rejected by the Spanish political and judicial establishment.

At the insistence of the UK government, middle-ground proposals (generally known as “devolution-max”) canvassed by various groups, providing for more devolution without independence, were excluded from the ballot.

Yet the apparent clarity of the Scottish referendum question hides deep ambivalence about its meaning and implications. Now that the referendum campaign has begun in earnest, both sides are having to spell out their offerings and both are moving into the very middle ground that the referendum was intended to exclude.

Independence as offered by the Scottish National Party has evolved into what is known as “independence-lite”, a hybrid constitutional form that resembles the “sovereignty-association”, “sovereignty-partnership”, “free association” or “confederation” concepts offered in the past by Quebec, Catalan, Basque and Flemish nationalists. Critics have highlighted the proposal to keep the British monarchy, but this is not really the problem, as the monarchy is as much Scottish as English and is shared by 15 other Commonwealth countries.

Money matters

More problematic is the proposal to use sterling as the currency of an independent Scotland. The SNP does retain a long-term option to enter the euro but politically this is, at present, a non-starter. There are various ways in which an independent Scotland could keep the pound, but the Scottish nationalists have opted for a full currency union, meaning that decisions on monetary policy and interest rates would be taken in London by the Bank of England.

As the experience of the Euro has shown, this implies elements of fiscal union, with binding rules about deficits and debts, and institutions to enforce them. The SNP insists that the currency will be shared, with Scottish representation in the Bank of England and joint control, but the UK government is adamant that this would not be on offer.

As the debate has unfolded, a series of other joint institutions and policies has been unveiled. Scotland would stick with the present regime of energy regulation and renewables subsidies, controlled from London. Various regulatory and service agencies could remain, with the justification that it would be too expensive to duplicate them. A recent expert report has recommended that, at least for a few years, the present administration of social security payments should be retained, which would greatly limit the scope for Scotland to make different policies. Suggestions have been made about co-operation in foreign affairs and defence – with the exception of nuclear weapons.

For their part, the unionist parties have felt obliged to make concessions towards more Scottish self-government. The Liberal Democrats have reaffirmed their commitment to a federal system for the UK - although, as long as they fail to say what they would do about England, it is difficult to see how this differs from stronger devolution.

The Scottish Conservatives debated the issue during their leadership election in 2011, when the losing candidate proposed to refound the party in Scotland on a radical “devo-max” platform. The successful candidate now proposes more fiscal autonomy for Scotland. The Labour Party has established a commission, including supporters of devo-max and staunch unionists, which has recommended the devolution of all income tax.

Much of the debate has focused on economics. While unionists have sometimes suggested that Scotland could not afford to be independent, they now feel as if this looks too much like talking down the country.

There is an official series of figures, Government Expenditure and Revenues in Scotland (GERS), which both sides accept as authoritative, but which they interpret differently. In fact, Scotland (unlike Northern Ireland or Wales) has a level of GDP per capita almost exactly in line with the UK average. If oil revenues are taken into account, its fiscal position within the UK is more or less in balance. The difficulty is that oil revenues fluctuate so that unionists argue that one should not base a national budget on them. Nationalists respond that they will create an oil stabilisation (or sovereign wealth) fund to even out the cycles, as the Norwegians have done. This may make a lot of sense in the long term but it would mean mean that oil revenues cannot also be used to sustain present levels of expenditure.

This debate is now starting to intersect with the debate on welfare reform at UK level. Some voices on the right have begun to argue for fiscal autonomy so that Scotland can cut taxes to attract investment – the counterpart being a smaller public sector. On the left, within the trade union movement and the voluntary sector, many now argue that only with more fiscal autonomy can Scotland sustain the welfare state now being cut back in England. The corollary of this is higher taxes.

The SNP has given the impression of being in favour both of low taxes and high welfare spending, revealing a division between a more neo-liberal and a more social democratic vision of independence. The Labour Party is equally conflicted, rejecting radical moves to fiscal autonomy and insisting that the welfare state is essentially a UK matter, but unable to say how Scottish Labour would respond if the UK continued in a neo-liberal direction.

And what of Europe?

Since the mid-1980s, membership of the European Union has been a central part of the SNP prospectus. It offers guarantees of open markets, labour mobility and an external support system for an independent Scotland. It also allows the nationalists to shake off accusations of “separatism” or isolationism. In the early phases of the independence debate, the SNP suggested that Scotland would automatically remain in the EU after independence.

Unionists, for their part, insisted that it would be outside the EU as of day one. European Commission president Jose Manuel Barroso even suggested that the acquis communautaire would cease to apply, and that Scotland would not be in the European single market. This is an issue that has clarified during the debate, following various academic interventions, and both sides have been proven wrong. Scotland would have to apply to join the EU, with the rest of the United Kingdom being the successor state. On the other hand, Scotland would not have to go through the lengthy accession process to which other candidate countries are subjected, because it is part of the EU and fully compliant with the acquis.

European law would not be suspended on day one, as it is part of the law of Scotland until repealed (as is UK law) and this could be affirmed with a single-clause act. It would be in nobody’s interest to disrupt the single market.

Unionists have also suggested that other member states would veto Scottish accession, fearing the precedent in their own countries – Spain and Cyprus have been mentioned. Scottish independence would certainly have political repercussions in these countries and elsewhere, but the position of the Spanish government is that Scotland would not set a precedent since there is a consensual process agreed with the UK parliament and a procedure. None of this applies in Spain. Other countries have indicated that they would follow the UK lead on recognising an independent Scotland.

The difficult questions, rather, concern the terms of Scottish membership of the EU - and it is here that countries like Spain might create difficulties with a view to showing that secession is costly. Unionists have suggested that Scotland would be obliged to join the euro and the Schengen free travel area, which would mean border controls with England. In fact, no country has ever been obliged to join the euro or Schengen against its will; Sweden does not have a Euro opt-out but has not joined. Difficulties would nonetheless arise on other UK opt-outs, notably on the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice, and there are questions about whether Scotland could, or would want to, adopt exactly the same pattern of opt-outs.

No status quo for the UK

This whole question has now been transformed by the Conservatives’ proposals for a referendum on UK membership of the EU in 2017. Having insisted that there is no third way on the Scottish question and that the choice is between independence and the status quo, David Cameron is arguing the opposite in relation to Europe.

There will be negotiation on a distinct status for the UK (a kind of devo-max within Europe), after which a choice will be offered between this and total withdrawal. There will be no status quo option, so that supporters of a strong Europe will be disenfranchised. The SNP has leapt on this to proclaim its pro-European credentials, announcing that the only way to stay in Europe is to vote for independence. Surveys have consistently found that, while Scottish voters are not enthusiastic about Europe, they are somewhat less Eurosceptic than those in England. More importantly, the visceral Europhobia found in parts of England is rare in Scotland and the challenge from UKIP is slight. So being pro-European does not carry the political cost which it would down south.

Ultimately, there is no simple solution to the Scottish constitutional conundrum, or indeed to the European one. Instead, Scotland will continue to seek a place within the multiple unions – UK, EU, NATO – within which it is embedded, and to defy conventional categories of constitutional analysis. This is an issue that will not go away whatever the outcome of the referendum next year.