As recent South Asian immigrants to Toronto, we write this article in response to personal contentious conversations about the Black Lives Matter movements and recent Wet’suwet’en protests with our South Asian families and community. Our arguments in support of these movements are often met with disdain. Even worse, we have encountered erroneous attitudes towards Black and Indigenous Peoples.

As South Asians, we are racialized but are also settlers on this land. Indigenous studies scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang explain: “Settlers are diverse, not just of white European descent, and include people of colour, even from other colonial contexts … Settlers are not immigrants … Settlers become the law.” Immigrants adopt the law of the land they move to, but if the land itself is stolen, then whose laws do we adopt?

As feminists and critical researchers of race, space and capital, we consider immigration to Canada to be part of the state’s capitalist and imperialist strategy to recruit new settlers. It is a way to keep Indigenous Peoples dispossessed and to render their and Black people’s labour undesirable.

In this way, racism can sometimes be treated by racialized immigrants as a white settler-Indigenous-Black triad. But critical race scholarship warns that we must not perpetuate Indigenous and settlers as a binary or opposite. Hence, any discussion of the precarious settlement of immigrants must also include an analysis of dispossession of Black and Indigenous Peoples. We need to identify settler colonialism as a structure and phenomena that simultaneously claws into everything: the cultural, political, social and economic.

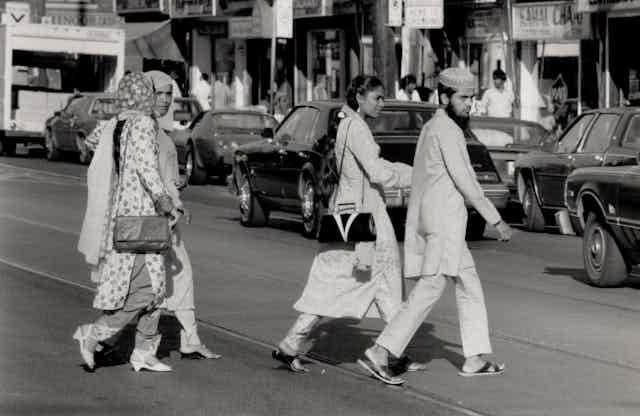

South Asians first arrived in Canada in the early 1900s from former British colonies including the Indian subcontinent, Africa and the Caribbean. They are currently one of the largest and fastest growing populations in Canada with growing socio-economic, political and cultural influence. Hence, it is imperative that we reflect on the presence of South Asians — as a body politic Canada — and their historic and current relationship to a racial capitalist agenda.

The model minority myth

South Asians are often depicted as a model minority by media and government. That is, we are seen and many of us see ourselves as racialized yet successful.

But the model minority concept has been declared a myth. Bonita Lawrence, Enakshi Dua, Beenash Jafri, Shaista Patel are just a few of the Canadian scholars that suggest it is a strategy to deepen racial divides and reinforce systemic racism.

Read more: How racism works and shifts during the COVID-19 pandemic

Ethnic studies scholar, Nishant Upadhyay, assistant professor at the University of Colorado explored the relationship between South Asian and Indigenous Peoples in Alberta’s oil sands. There they say the racialized model minority figure is “rendered complicit” and “used in the service of white supremacist colonial-capitalist projects” that constructs Indigenous and Black people as the “unmodel other.”

Sociologist Sunera Thobani explains how capitalism relies on racialized immigrant labour. According to Thobani, “forever-foreign” immigrants generally excluded from nation-building, seek inclusion in the state through laboured citizenship. In doing so, they become part of a state system that negates the labour of Black and Indigenous Peoples.

This can be traced back to the 1800s when the British used the labour of South Asians to expand and protect their empire across Fiji, Mauritus, Africa and the Caribbean. This is not to disregard the violence or racism against racialized immigrants but instead to say that we must be aware of the histories and the continuum of this violence within Canada.

Colourism and casteism in South Asia

In South Asia, colourism against dark-skinned South Asians is a long-standing issue. Casteism and the associated oppression of and violence against Dalits is rampant.

Oppression of the African diaspora in South Asia as Sidis in India, Sheedis in Pakistan and “Kaffirs” in Sri Lanka is common. The dispossession of and violence against Adivasis, the Indigenous Peoples of India is either made invisible or deemed necessary for development.

Dalit scholar and architect of the Indian constitution B.R. Ambedkar pointed out that these divisions have historically been deepened by centuries of British colonial rule and indicate a loss of strength in our inability to stand up to racism.

Read more: Novelist Arundhati Roy and her mission to inspire in the Ministry of Utmost Happiness

Anti-racism for South Asians

Recently, the faculty of education at York University held a panel discussion with professor Vidya Shah and former education officer at Ontario Ministry of Education, Jeewan Chanicka to reflect on the need for more visible and loud anti-racist agendas in South Asian collectives across Canada. Shah spoke of a “long silence” against anti-Black racism, specifically in Ontario. Herveen Singh, faculty at Zayed University, also remarked that “the [brown collective] silence has been deafening when Black lives are under siege.”

Singh and Shah’s conclusions are anecdotal and more research is needed in this area. A search on social media indicates some South Asian groups advocating for anti-racist allyship.

There is also ample evidence of political activism of Canadian South Asian collectives from the 1990s. For instance, Desh Pradesh (initially known as Salaam Toronto, first organized by Khush: South Asian Gay Men of Toronto) was created to address the systemic exclusion that South Asians faced in Canadian cultural life.

And historically, anti-colonial resistance has been densely interwoven with anti-racist movements. For example, in “1942, the Black press was heavily covering the widespread anti-colonial civil disobedience in India.” In the same decade, exchanges between W.E.B. Du Bois and Ambedkar indicate the connection between the struggles and actions for liberation between Dalits and Black peoples.

We feel we need a larger presence of South Asian collectives to deconstruct the notion of the Canadian state in relation to our treaty obligations while remaining cognizant of the rich social and cultural history of Turtle Island.

Regarding South Asians who are new Canadians, we need to ask why newcomer settlement services do not include knowledge on whose traditional lands we have landed. We must demand a focus on history and continuity of struggles as well as the successes of Indigenous and Black peoples. We must associate with Calls to Action as recommended by the Truth and Reconciliation Committee.

Institutional and community setups for South Asians must amplify voices that disrupt daily practices of racism, colourism, casteism and oppression. With our complex colonial legacies of anti-Blackness, we must simultaneously look inward, while reflecting outward.