The nine films that comprise the Melbourne International Film Festival’s Experimental Shorts program confront viewers with questions about image, form and genre. The Experimental Shorts program is an annual feature of the festival, one that is eagerly anticipated by aficionados of the avant-garde – and it challenges audiences to reflect on what’s real onscreen.

Daylesford-based filmmaker Richard Tuohy’s 20-minute black-and-white flicker film Dot Matrix opens the night. It features two 16mm projectors firing at the same 4:3 screen space over the heads of the audience. The ornate EIKI 16mm projectors are the first thing the audience sees upon entering the cinema.

Tuohy and his partner Dianna Barrie are preparing to monitor the performance – and when the lights go down, projector reels and hands are silhouetted by flashlights upon the cinema’s ceilings and walls.

The film’s white and black dots begin to pour out onto the screen in front of us. The images you see are also what you hear in this expanded cinema work. Skittering runs of stereo blips stutter out of the cinema’s sound system. The dots appear not only on the screen but across the optical soundtrack of the film.

What’s so experimental about this short?

The Experimental Shorts program is one of eight sessions devoted to short films at MIFF this year. It is easy to wonder, as the nine shorts in this session are screened, sometimes in complete silence, what ties them together. What makes a film “experimental” – as opposed to “animation” or simply “WTF”?

Between them, the Experimental Shorts sessions present a crooked history of artist-made cinema – and they remind us just how unhelpful the term “experimental” can sometimes be as a qualifier.

The tradition of avant-garde and experimental filmmaking ensures it is always at least aware of its proximity to modern art. This is especially the case with the final film of the program, Laure Prouvost’s digital assemblage Grandma’s Dream.

Prouvost won the Turner prize for her earlier work, Wantee (2013), the precursor to this nine-minute account of contemporary art as a post-conceptual and cultural-consumer dystopia. The sky appears to blush as lo-fi images of a white BMW pop up and a child-like voiceover narrates the imagined wishes of a fictional and ironically absent older generation.

Nine shorts, one feature?

All of the films shown are premiering to Australian audiences. Unsurprisingly, they’re short too, being anywhere between five to 20 minutes in length. The length might seem somewhat arbitrary – but they add up to a total program that is about the same length as a common feature film, just right for efficient consumption by a festival audience. The result is often a confusing collection of disparate images.

The selection panel for this year’s program have done a good job of creating some sense of continuity between the films. This means there is also a kind of meta-narrative linking the program. Familiar themes of space and time emerge after New Zealand filmmaker SJ Ramir’s grainy No Place To Rest is followed by Eve Heller’s cut-up of found footage sci-fi and kitsch.

The black and white of Dot Matrix gently gives way to colour. The penultimate work on the program, Pablo Mazzolo’s Photooxidation, shows a young boy, who appears to be blind, staring out unfocused at the camera while chaotic scenes and images in quadroscope flow around him.

Rainer Kohlberger’s digital experiment in colour and sound, humming, fast and slow, like cinema-assisted synaesthesia, recapitulates Tuohy’s more classic cinematic pose, now with digital raster effects.

Narratives for our time

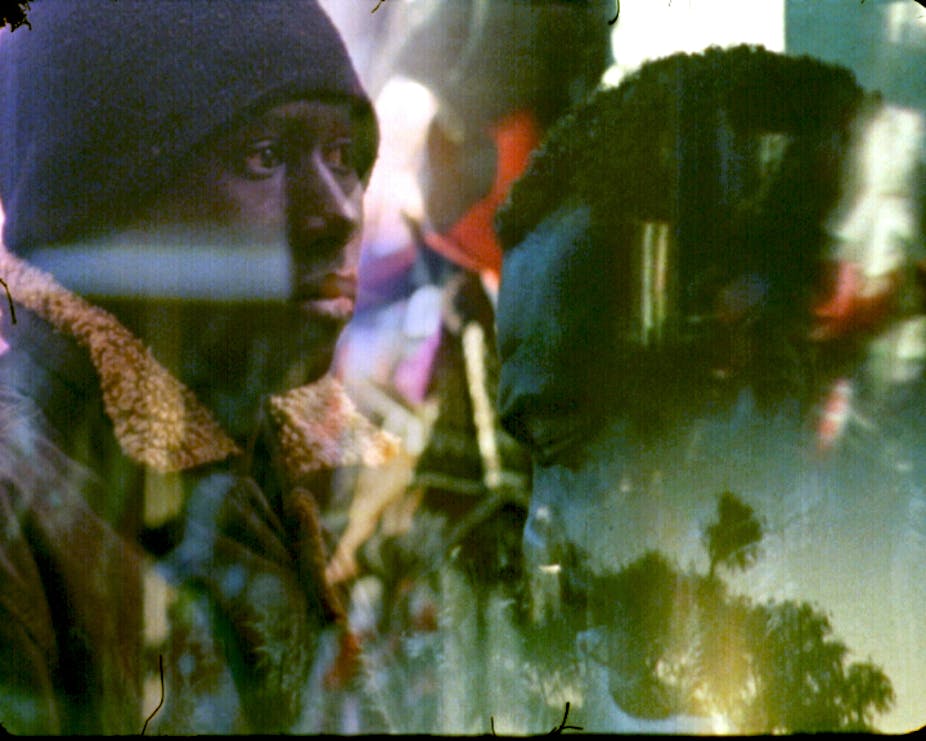

The centre of the program is American filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky’s silent film Song. Shot on glorious 16mm colour stock from the beginning of October 2012 through to the northern winter solstice of that year, the stunning vision of this master filmmaker reduces the form of experiment to one of neat composition, framed only by the lens onto the world.

Double exposures are produced through reflections of San Francisco streets in shop windows while interiors appear so muted they become otherworldly. Following directly in the lineage of the independent American cinema of the 1950s and after, Dorsky’s cinema is tied to the post-Emersonian landscape idealised by film critics such as P. Adams Sitney. The film is a poem of images, the expression of an artist whose medium is the industrial stuff of modern movement.

Michael Robinson’s looping The Dark, Krystle follows, providing a kind of comic relief as Dynasty-era soapstars are ordered to play the same scenes over and over again. In 45 7 Broadway, Tomonari Nishikawa’s colour-separated images of contemporary New York reveal the cinema’s deep link to an image culture that retreats to the surface and feeds only on light.

Ultimately, the same questions are being asked here again and again: what is time in the age of the cinema? What space do we inhabit collectively in the screen and together in the half light of this industrial apparatus?

Without experimental cinema, unafraid to break with the suspension of disbelief, the cinema effect would not have a ground zero.

The Melbourne International Film Festival 2014 runs until Sunday August 17. See all MIFF 2014 coverage on The Conversation here.