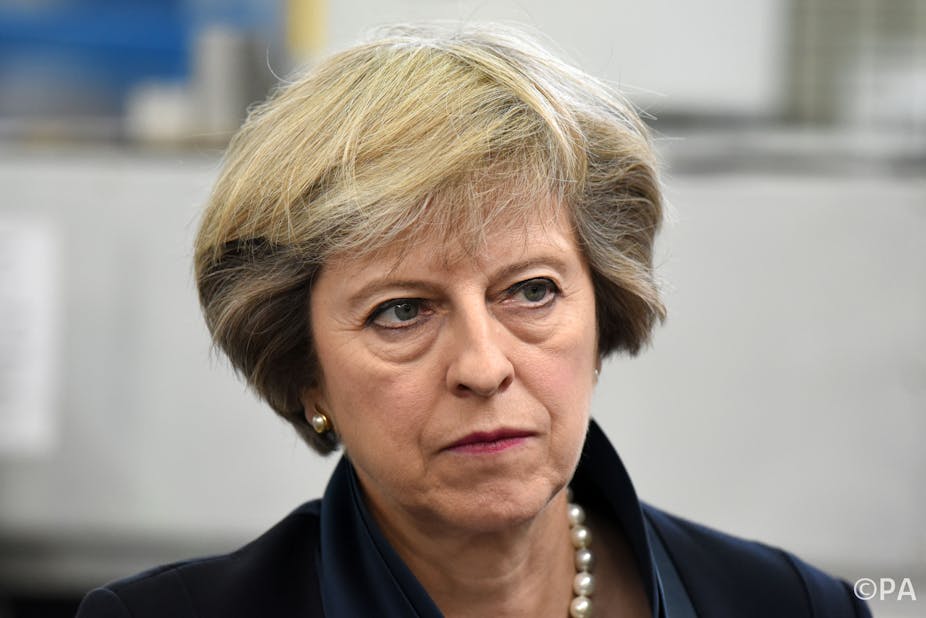

“Brexit means Brexit,” declared Theresa May before the government shut down for the summer. As holding phrases go, this was not bad at all. It gave the impression of purpose and clarity. While time will tell whether the new prime minister possesses the former, the latter already appears conspicuous by its absence. So what, then, might Brexit mean? When, if ever, might it be achieved? And what form might it take?

Let’s deal with timing first. While David Cameron did not hang around to deal with the fallout from his referendum, he did shape the timing of what was to come. He insisted that nothing could be done until a new government was in place, thereby contradicting his own assertion prior to the referendum that he would trigger Article 50 – the mechanism to leave the EU – immediately after a vote in favour of Brexit.

His successor does not appear in any great hurry to do so either. The various officials I’ve discussed this with seem to think Article 50 will be triggered in either January 2017, or conceivably June 2017, after the French presidential election.

Reasons to delay

In many ways, it makes sense to delay the process. For one thing, it will take time to figure out what, politically, an acceptable deal would look like. Theresa May faces the unenviable task of attempting to create a coalition behind whatever settlement she decides to aim for. And the profound divisions in the country that the referendum cast into stark relief – between the various nations of the UK, between rich and poor, between cities and countryside, the educated and uneducated, the young and the old – make that, to put it mildly, a challenging task.

It is probable that no deal can attract widespread political support. The so-called 48%, including the Scottish government, and a large majority of MPs, would rather the UK did not leave. The Leavers themselves are bitterly divided. On one side are the “liberals” such as the foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, who favour immigration, and see Brexit as a means of reinforcing Britain’s internationalist outlook. On the other, the nativists, including many UKIP supporters, who see Brexit as a means of pulling up the drawbridge and of limiting immigration to this country.

And that is without mentioning the ideological spilt between Leavers who viewed the EU as a capitalist conspiracy against the working class and those who thought of it as a socialist plot – a nanny state on a continental scale, intended to erode Britain’s competitive advantage.

Early polling has illustrated the potential problems. A YouGov poll in August found that, while 36% of respondents thought it acceptable for a pre-Brexit Britain to follow EU regulations, 64% thought a “hard Brexit” – implying no continued membership of the single market – would better respect the outcome of the referendum than a soft Brexit.

Equally striking is opposition to Britain making any payment to the EU budget. The same YouGov poll found that 44% of respondents would find any continuing financial contribution by the UK to the EU unacceptable. A subsequent Lord Ashcroft poll put that figure at 81%.

Taking time to take stock, then, makes sense, if only to test the ground at home. And it also provides the space to begin informal negotiations with the rest of Europe. EU leaders have been publicly adamant that such talks cannot happen prior to the triggering of Article 50. Not least, their distrust of each other means that they do not want Britain to be able to engage in 27 separate sets of talks prior to coming to the formal negotiating table.

Yet in reality, the contacts have already started. Tentatively, for sure, but given the scale of what needs to be achieved during the meagre two-year period allowed under Article 50 there really is no alternative.

And it is is important not to underestimate the problems involved here. All other member state governments have political pressures to contend with, as we will see as French rhetoric ratchets up ahead of their presidential election next year. Politics and posturing will not be a purely British problem as Brexit progresses.

So delay makes sense, though not indefinite delay. As the prospect of an early British general election recedes, the need to get Brexit sorted out before the scheduled date of May 2020 becomes more pressing. The Conservative government will not want that vote to be dominated by the EU. Realistically, therefore, Article 50 must be triggered in or by the autumn of 2017.

The long game

So much for process. What about substance? The first point, too often overlooked, is that Article 50 has nothing to do with the future. It is all about tying up the loose ends of membership. The issues will be important: ranging from British participation in EU programmes such as the Horizon 2020 research funding stream, to contributions to the EU budget, to the pensions of and arrangements for the British nationals who work in the EU. But they will not be the crucial ones that shape the relationship between the UK and the EU for the foreseeable future.

These latter negotiations are formally separate from those over Article 50, though they will doubtless take place in parallel. And, crucially, they will almost certainly take longer than two years to bring to a successful conclusion, even should Article 50 only be invoked in June of 2017.

Herein lies the crucial problem. Exiting the EU without a deal would mean reversion to a World Trade Organisation-type relationship that would harm both the UK and the EU.

The only alternative, in my opinion, would be for the UK to negotiate some kind of transitional deal with its partners. Under this, as I’ve argued, with Damian Chalmers in more detail in a recent paper, Britain would leave the EU relatively soon, so respecting the outcome of the referendum, while mechanisms for managing the relationship for, say, five years, could be put in place, leaving the time for negotiations on a final settlement to be successfully concluded.

Even then, of course, there is no guarantee that such a deal would secure widespread approval at home, or the necessary unanimous approval among EU member states. No one is claiming that this will be easy. But it makes sense to play the long game.

This article was co-published with the UK in a Changing Europe initiative.