To strike or not to strike? That is the question union leaders tangle with every time the prospect of an industrial stoppage looms. It is a fine line that divides public support from public condemnation.

Commuters on the Southern rail service have had their working week severely disrupted by two days of strike action that have left many people unable to get in and out of London. These commuters are the key battleground for both Southern management and the striking rail union, the RMT, who are angry over plans to have a driver on trains and no other staff/conductors. But will those angry people left standing on the platform think that Southern management has a case to answer – or will they blame the union for making their lives difficult?

This is always the key issue in service sector strikes. Whether or not the public sees industrial action as justified, people are still put out. The objective for both sides is to win the PR war.

A strike is widely seen as a weapon of last resort and it’s imperative that the union gets the message across that attempts to get a negotiated settlement have failed – in this case, both sides claim the other has blocked a negotiated settlement. To strike too soon can jeopardise much-needed public support, whereas a union that has the support of those it is affecting most finds itself in a stronger bargaining position.

Timing is everything

It seems that service sector strikes are timed to cause the greatest disruption. Historically, postal workers have struck in the run-up to Christmas. The Fire Brigades Union picks Guy Fawkes night. Strikes on the railways and airlines tend to occur in the summer when holiday travel increases. In coal mining, the National Union of Mineworkers relied on “General Winter” to give them the edge over the government.

Service unions face a dilemma – how can they increase their power by creating maximum disruption and inconvenience to customers, yet keep the customers on side. For the company, it’s about walking a tightrope – one the one hand it needs to demonstrate how reasonable they are to win the hearts and minds of paying customers. But on the other hand, it’s about showing strength to give their shareholders confidence and to keep the share price healthy.

Once the decision to call a strike has been taken, the full weight of the union and management PR machinery will be brought to bear in the form of regular press releases, bulletins, flyers and web updates. In the ongoing dispute with Southern, bullet points on the RMT’s “why we are striking” flyer stress: “Your safety under threat”. Nothing like a bit of scare tactics to garner public support.

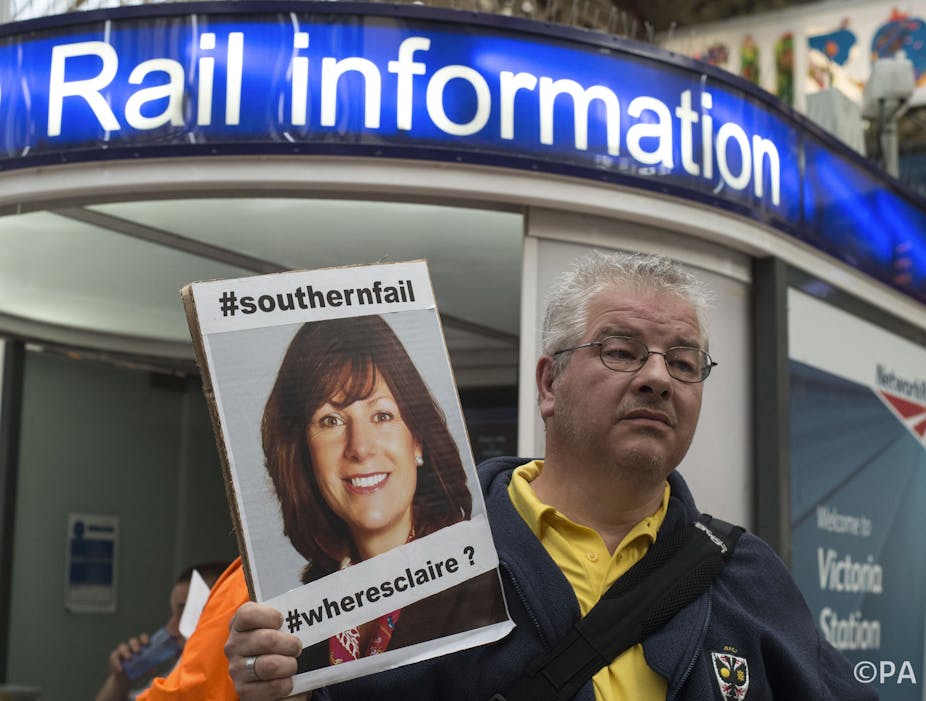

The growth of social media has made PR more agile than ever. Twitter feeds and Facebook posts are used by companies and unions to convey their messages. But whereas two decades ago PR tended to be controlled by the organisation or the union, the use of social media has turned out to be a double-edged sword. The public have the ability to take to Twitter to vent their anger and to challenge the company or the union.

Claim and counter

Beleaguered passengers on Southern have endured months of disruption as conductors – guards – strike over a change to their role. The dispute is about who should close the train doors, the conductor or the driver. Proposals to replace conductors with on-board supervisors are hailed as modernisation by Southern’s management. Conductors are accused of being Luddites, of holding back progress. The RMT union argues the dispute is about passenger safety – something will always raise doubts in the minds of passengers.

Drivers complain the technology they will be relying upon to close the doors is inadequate. They argue the acute angle of the on-board cameras, combined with their susceptibility to bright light or darkness, makes visibility so poor that it threatens passenger safety. Visual images on the on-board camera monitors appear to support the driver’s concerns.

Southern has countered the argument by stating that many trains already run with driver-only operation (DOO). It further argues that the Rail Safety Standards Board has no concerns – but, given the RSSB is funded by the train operating and infrastructure companies, there could well be a conflict of interest involved here.

The most recent major dispute on Britain’s railways was in the summer of 1994 between the RMT and Railtrack (now Network Rail). The nationwide dispute revolved around the pay and restructuring of signal workers. Over the summer, passengers endured a series of 24 and 48-hour strikes. On August 14 1994, Railtrack spent between £80,000 and £100,000 on national newspaper advertising in an attempt to win public support. On the same day a MORI poll showed that the RMT was winning the PR battle with 56% of the public backing them.

Tough medicine

The current dispute between junior doctors and the government over the new contract further highlights the union PR dilemma. The NHS is a bit like an insurance policy – you need to have it, but you hope never to need it. It could be argued that the junior doctors were hasty in their decision to call for five consecutive days of strike action each month. They certainly attracted high levels of condemnation. The cancelling of the September strike indicates they knew their PR campaign was fragile. This was not helped by the British MA’s who are Mark Porter giving unconvincing interviews about support for the strike. The BMA Council voted 16 to 11 in favour of the strike with seven abstentions.

Much of the success in the PR battle depends on the turnout in the strike ballot and the level of support. Votes for strike action in ballots with a higher turnout give a stronger mandate than lower ones. When the Trade Union Act 2016 comes into force over the next 12 months, strikes in “important public services” will require a turnout of at least 50% and that at least 40% of those entitled to vote must be in favour. That’s a tall order as many of the strikes in the past five years or so fell well short of this threshold.

However, calling a strike on the basis of 70% vote in favour on a turnout of 30% plays straight into the hands of management – it reflects that the will of workers to strike is well below half the workforce. In April this year the RMT conductors vote was 95% in favour of strike action on a turnout of 82%, so around 78% of conductors support the strike.

If social media is to be believed, the RMT is winning the PR battle with Southern at the moment. Despite months of delays, cancellations and reduced timetables, it appears management are feeling the brunt of passengers’ anger. But how long will it be before they turn on the RMT?