Blues … Black … Darker than grey/ Creation sounds Gold Reef Mine rockfall crush-sounds/ Guitar-string gun-spit tear flesh/ Black sonic science/ Darkest Acoustics … (from Where Are The Keys? on Group Theory: Black Music)

South African poet Lesego Rampolokeng often writes about Black music in his poems. His collaborations with musicians on record are rarer but always remarkable. There was the casette-only 1994 African Axemen collaboration with Zimbabwean Louis Mhlanga and a stellar crew of other pan-African guitarists. And his Tears for Marikana on Salim Washington’s album, Sankofa. And now the track Where Are the Keys? on South African drummer and composer Tumi Mogorosi’s fourth outing: Group Theory: Black Music.

What makes the collaboration so satisfying is the shared skill of both Rampolokeng and Mogorosi in signifying. Not the “signification” of semiotics, but the righteous, subversive signifying perfected by the Black churches and theorised by US literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. For him signifying is “the practice of representing an idea indirectly, through a commentary that is often humourous, boastful, insulting, or provocative”. Communities repurpose ideas; poets like Rampolokeng do it via wordplay; jazz musicians, every time they improvise.

So when Black South African jazz players, decades ago, heard and admired American jazz on record or at the movies, they not only copied the styles and approaches. They also employed many ways to “make it our own”. When Peter Rezant’s Merry Blackbirds recorded the international standard Heatwave in 1939, for example, they played the tune straight – but the words, in an African language, became a praise song for the band’s national prowess.

Tumi Mogorosi

Musician, activist and scholar Mogorosi started his musical career as a chorister in church. So, it’s not surprising that part of his signifying has often been through working with voices. From singing, he moved to guitar and later drums. At 18, he studied music at the Tshwane University of Technology. He now has a master’s degree in fine arts and is registered on a doctoral programme.

Along the way he produced his 2014 debut album, Project ELO (from a sextet with four accompanying voices). In 2017 he was part of the Swiss-based Sanctum Sanctorium with its allusion to sacred rites. He worked internationally with, among others, UK saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings.

Those international collaborations set the scene for the joint release of the new album between South African label Mushroom Half Hour and UK imprint New Soil. In 2020, in a trio called Wretched with vocalist Gabisile Motuba and guitarist Andrei van Wyk he improvised and experimented with vocals and noise.

The album

Group Theory: Black Music has echoes of all those, but is a sonically distinct new project. The album’s notes refer to two musical sources, from South African and American jazz traditions. The rich South African vocal tradition of jazz composers like Todd Matshikiza and Victor Ntoni, and the work with voices of radical American jazzmen like Max Roach, Billy Harper and Andrew Hill.

Mogorosi says:

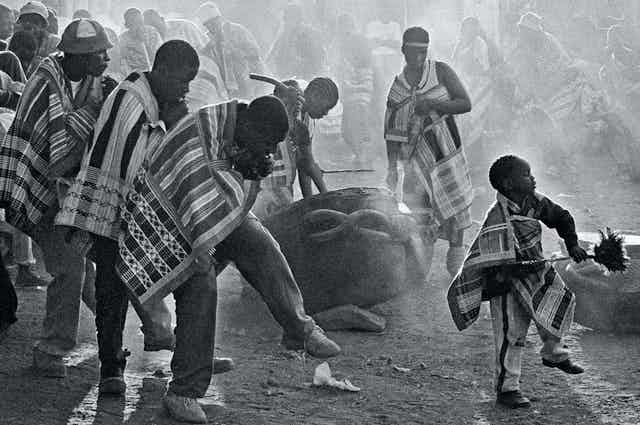

(Black voices in concert have) this idea of mass, of a group of people gathering, which has a political implication. And the operatic voice has both a presence and a capacity to scream, a capacity for affect. The instrumental group can sustain the intensity of that affect, and the chorus can go beyond improvisation, towards communal melodies that everyone can be a part of.

So, alongside the jazz quintet (Mogorosi, reedman Mthunzi Mvubu, trumpeter Tumi Pheko, guitarist Reza Khota and bassist Dalisu Ndlazi) the tracks employ a nine-voice chorus, predominantly singing in unison to shape the communal voice. There are also two guest vocalists, Motuba and Siyabonga Mthembu, each providing a very different interpretation of the traditional Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.

That choice of song (the only one not composed by Mogorosi) makes explicit the community and spiritual traditions shared by Africa and the Black diaspora. Mthembu’s take on it is inspiring, heartfelt and soul-infused: the massed voices echoing the historic style of the Howard Roberts Chorale. Motuba’s voice is more subversive: underlined by Khota’s guitar improvisation, she fractures lyric and phrasing deliberately to build tension with the choir.

The very distinctive instrumental voices, and the presence of veteran piano guest Andile Yenana, also interrogate conventional roles in an ensemble. Who is a leader and who a composer when each sonic element cedes and creates space for the ideas of others. Far less smooth is the sound of the chorus on Thaba Bosiu, the track featuring Yenana, where fragmented textures and that capacity to “scream” that Mogorosi notes come to the fore over urgent, imaginative improvisation from drums, guitar, piano and bass. The track is faded out (it’s a long album), but that’s the one I wanted more of.

The theory

The theoretical underpinnings of the album are many. The title Group Theory: Black Music foregrounds three: association, identity and closure. But there is nothing dry and theoretical about the sound. It’s warm, human and at points more tuneful than some of Mogorosi’s previous work.

The drummer quotes jazz historian and critic Amiri Baraka’s proposition about the “New Black Music” of another era – “Find the self, then kill it” – to point to the collective and global struggle to generate new identities, ideas and sounds from those who were previously hemmed in.

The closing track, Where Are the Keys? with the prominent presence of veterans Yenana and Rampolokeng, and the poet’s encyclopedic stringing together of all the music’s sonic, intellectual and revolutionary influences, ties everything together.

Reading the poetry (which is supplied) is a rich source of perspectives for all kinds of thinking beyond the edges of a record. The situation of war, poverty but also creativity into which the music is published means that, right now, closure isn’t an answer; it’s a question too:

Slash that … vinyl scratch/ The pain slides through the gash/ Tripping off morning horns/ Past the dawning…