Infections and deaths caused by superbugs are increasing every year. So the government’s five-year strategy to tackle the problem, if a little tardy, is a welcome step.

In January, Chief Medical Officer Sally Davies said antimicrobial resistance posed such a catastrophic threat that within 20 years we could return to a pre-antibiotic era where people die from routine infections because we have nothing to treat them with.

Production stalled

Many existing antibiotics are no longer effective and their production has stopped. The number of antibiotics available for use by doctors has reduced by nearly 25% and in life-threatening situations where MDR organisms cause infections in the critically ill, old antibiotics (which are often toxic) are used in an attempt to save their life.

The development of new antibiotics is at an all-time low and many pharmaceutical companies have changed the focus of their research and development programmes to meet the treatment needs for lifestyle illnesses such as diabetes and obesity.

The speed and cost of developing a single antibiotic, estimated at £300-£550m, can be prohibitive. The associated scientific and regulatory challenges make this type of project riskier than other drug-related research.

Totally new discoveries are rare but the potential to find new bacteria to culture is there.

Better late than never

The government’s strategy has three major aims in slowing the development and spread of antimicrobial resistance: improve knowledge and understanding; conserve and steward the effectiveness of existing treatments; and stimulate the development of new antibiotics, diagnostics and novel therapies.

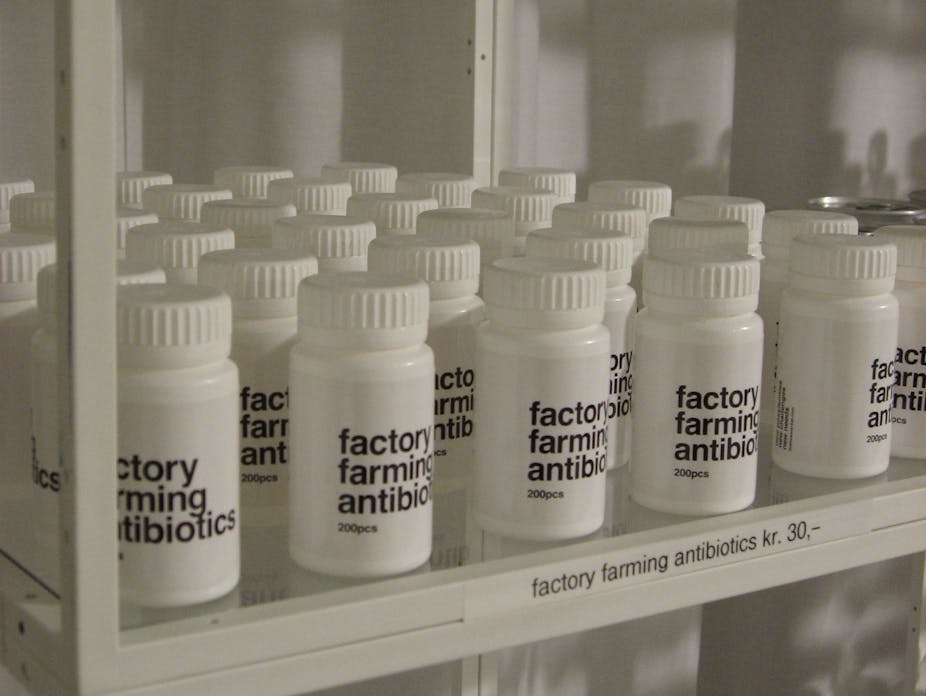

It has promised major investment in areas including improving infection control in people and animals through better hygiene, surveillance and monitoring; improving farming practises; education and training in health-care on appropriate use and also importantly, collecting better data on resistant bugs so we can track them more effectively, find the most resistant bacteria and step in earlier.

In addition the strategy sets out to encourage further development of new antibiotics, rapid diagnostic methods and alternative treatment strategies and provide £4m in funding to set up a new research unit to focus on antimicrobial resistance and health-care associated infections.

Demand on the National Health Service is probably greater than ever before. Medical advancements are exciting and we now expect to survive conditions we’d previously have died from. However, it is the introduction of some of these advancements and the lack of understanding of the interaction with the microbial community that has helped create the problems we are now facing.

Adapting fast

The threat posed to our health is palpable. Common organisms that are capable of causing disease, such as Staphylococcus aureus, have acquired pieces of DNA (genes) that have allowed them to survive in the presence of antibiotics. These organisms have continued to acquire more genes and are now resistant to the majority of antibiotics and are known as multiply drug resistant (MDR).

Multiple drug resistance is also found in organisms that cause tuberculosis, and infections in the skin, chest, blood stream and gastrointestinal system to name a few.

Bacteria, viruses and fungi are all adapting to their environment and in hospitals and other health-care facilities where antibiotics are frequently used (sometimes inappropriately), this has occurred with alarming speed.

The first case of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) occurred a few years after the introduction of the antibiotic in 1961, but it wasn’t until the late 1980s and early 1990s that the numbers of cases rapidly increased. It is now a global problem and frequently causes health-care associated infection.

Although major investment has been made to minimise the spread, for example through infection control, a “wash your hands” campaign and alcohol hand gels, it’s now unlikely to disappear from hospital altogether.

We are now seeing this organism in the community too. Worryingly, other common organisms found in hospital areas are also becoming multiply drug resistant and are found contaminating some of the medical equipment used in critical care.

We must conserve the antibiotics we have left by using them effectively. And the process of developing new antimicrobials and getting them to market safely must be accelerated. We also need to further develop a rapid diagnosis of MDR infections to allow more targeted treatment rather than using antibiotics with a shot gun approach.

We all - doctors, patients, the public and farmers and animal keepers who use antibiotics - need to understand the value and importance of antibiotics and the dangers of inappropriate use. I

The interaction between man, microbe, environment and the drugs that we develop needs to be fully understood. The new strategy is a great step, but as resistance grows we need to move much faster and keep up the momentum. Let’s hope it isn’t a little too late.