This article is part of a series on the Future of VET exploring issues within the sector and how to improve the decline in enrolments and shortages of qualified people in vocational jobs. Read the other articles in the series here.

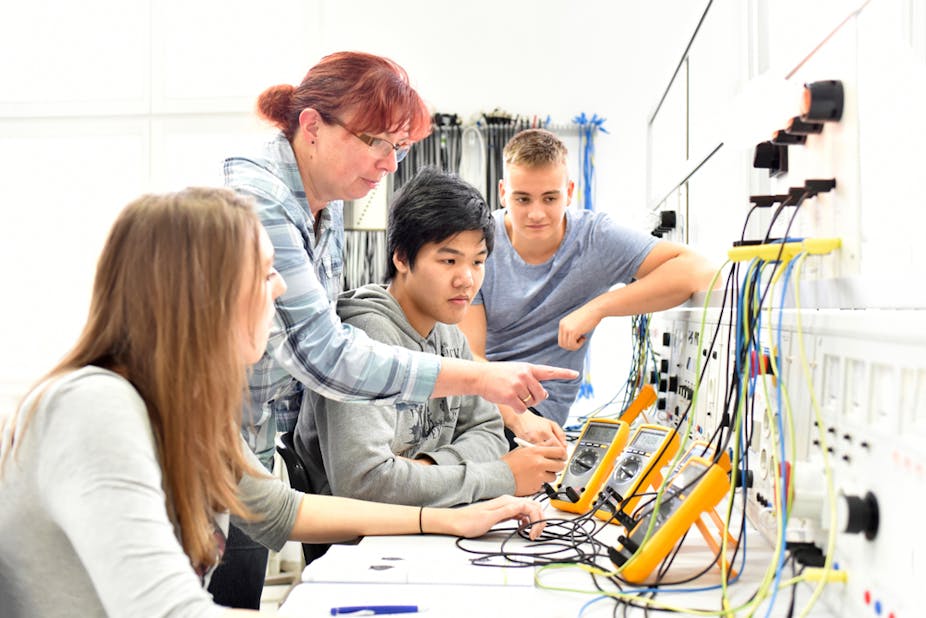

Vocational Education and Training (VET) is an important part of the education sector and trains people of all ages for occupations vital across all sectors of the economy. It also makes a major contribution to social inclusion.

Australia endlessly debates the ATAR level needed even to enter teacher-training programs for school teaching.

Read more: Viewpoints: should universities raise the ATAR required for entrance into teaching degrees?

But it doesn’t seem to care about the qualifications of those who teach our young people, workers and citizens in VET. For the last 20 years, VET teachers have only been required to have a Certificate IV level qualification in VET teaching, and the industry qualification at the level at which they are teaching people.

Teacher preparation has been identified as a key factor in the quality of education, so to improve the quality of the VET sector, we need to ensure teachers and trainers are getting the right training themselves. Other factors – such as funding – affect VET quality and student success.

But, in the school sector, it has been shown teachers make the most difference, so the same is likely to be true of VET. Teaching in any sector is a highly skilled activity and VET, especially, has such a range of learners that diverse teaching strategies are needed.

Who are these teachers and trainers?

VET teachers work in TAFE (the public provider) private registered training organisations (RTOs), community colleges or enterprise RTOs (providing qualifications to their workforces). They may teach full-time, have a portfolio of jobs across several providers, or may still work in their industry while they teach part-time.

They are “dual professionals”, needing to keep up with changes in industry, the economy and society, and developing their teaching skills to deal with increasingly complex learner groups and teaching environments.

Until 1997, all full-time TAFE teachers nationally were helped to get degrees in VET teacher training after recruitment, or graduate diplomas if they already had a degree in another area. They studied part-time while teaching.

Read more: Expert panel: what makes a good teacher

In 1998, the minimum qualification – the Certificate IV level – was introduced for all VET teachers and trainers. States and territory TAFE systems gradually stopped requiring higher-level qualifications. The Certificate IV floor became a ceiling.

While some teachers undertake higher-level study, they are now the minority. Yet, those who undertake higher level qualifications can clearly point to their value.

Where’s the evidence these qualifications benefit teachers?

Our national study, conducted from 2015 to 2017, looked at whether and how VET teachers’ qualifications made a difference. The project had seven phases of qualitative and quantitative research over three years, with 1,255 participants from the sector, from all types of training provider and industry areas. We had good numbers of teacher participants at all qualification levels.

In TAFE and RTO case studies for this project, we interviewed supervisors, managers, professional development staff and students as well as teachers.

Based on detailed survey responses and our case study results, we found:

higher level qualifications, either in VET teaching practice or another discipline improve teaching approaches, confidence and ability

higher level qualifications in VET teaching specifically make a significant difference to VET teachers’ confidence in teaching a diversity of learners

the qualification level that makes the most difference is a degree.

How many VET teacher are qualified at different levels?

There is no national source of information on how many VET teachers are qualified at different levels. In our main survey, twice as many VET teachers had degrees in their industry area (37%) as had degrees in VET teaching (19%). Some 27% had qualifications only at Certificate III or Certificate IV in their industry area, and 64% had only a Certificate IV qualification in VET teaching.

By far, the greatest proportion of teachers sat in the lowest qualification combination (sub-degree qualification in their industry area and Certificate IV in VET teaching). Only 11.9% had qualifications at degree level or above in both their industry area and in VET teaching.

But our study showed teachers with degree-level knowledge in teaching and their industry area were the most confident in passing on knowledge and skills to their students. Some teachers with lower qualification levels did show the characteristics of excellent teaching, but these were more common in highly-qualified teachers.

What’s stopping VET teachers from qualifying themselves?

Perhaps the existence of a mandated minimum VET teaching qualification may provide an excuse not to progress further than the minimum. Some people think professional development can act as a substitute for qualifications – but our study found people with lower level qualifications undertake less professional development.

In most jobs, professional development supplements rather than replaces initial qualifications. Perhaps resourcing is an issue. TAFE teachers may expect their study to be supported by employer funding and a workload allowance, neither of which may be possible.

Some people imagine to get a university qualification in VET teaching, people must give up their jobs and go to university for three years. This could, of course, be difficult if it were true - but it isn’t.

All VET teacher-training courses at universities are part-time and offered flexibly, as most students are working full-time in VET or in industry and may live at a distance. Universities work closely with individual TAFE and other providers in making their VET teacher-training courses relevant.

What could help VET teachers become more qualified?

Already, a higher level qualification in adult education (the Diploma of VET or university degree) is recognised by the VET regulator, the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA), as an alternative to the Certificate IV. VET teachers must now show continuous professional development in VET as well as in industry. Undertaking a VET teaching qualification can meet this requirement.

A more open attitude from some in the VET sector – allowing teachers to attain higher-level qualifications rather than the sector insisting only on educating its own – would help. Ambassadors, such as graduates of higher level courses, could spread the word about what they’ve gained from their studies, personally and in their careers.

Federal and state government could introduce policy provisions to improve teacher/trainer qualification levels, as they do with school teaching and have done with early childhood education.

Read more: Teach for Australia: a small part of the solution to a serious problem

Finally, a “Teach VET for Australia” program, similar to Teach for Australia would be useful. The idea of taking adults with life experience and training them as teachers is what VET teacher-training has done for decades. A named and targeted program could demonstrate the benefits of higher-level qualifications.

The author would like to thank Keiko Yasukawa, Roger Harris, Jackie Tuck, Patrick Korbel and Hugh Guthrie who were researchers on the ARC-funded project, and Steven Hodge who was involved in an earlier project.